If "The Cell" were six minutes long it would blow your mind. At two hours, it's a disordered muddle of hellacious highs and pedestrian lows. Astonishing in places and generally pointless, it's unquestionably the special-effects champion of the summer. Although I found Bryan Singer's down-tempo "X-Men" quite agreeable, it was low-impact spectacle, as if meant to inaugurate some new age of Hollywood austerity in the post-"Matrix" era. Seizing his first feature film by the throat and choking it into a hallucinatory coma, commercial and music-video director Tarsem Singh (who has been known until now simply as Tarsem) quickly announces he's having none of that.

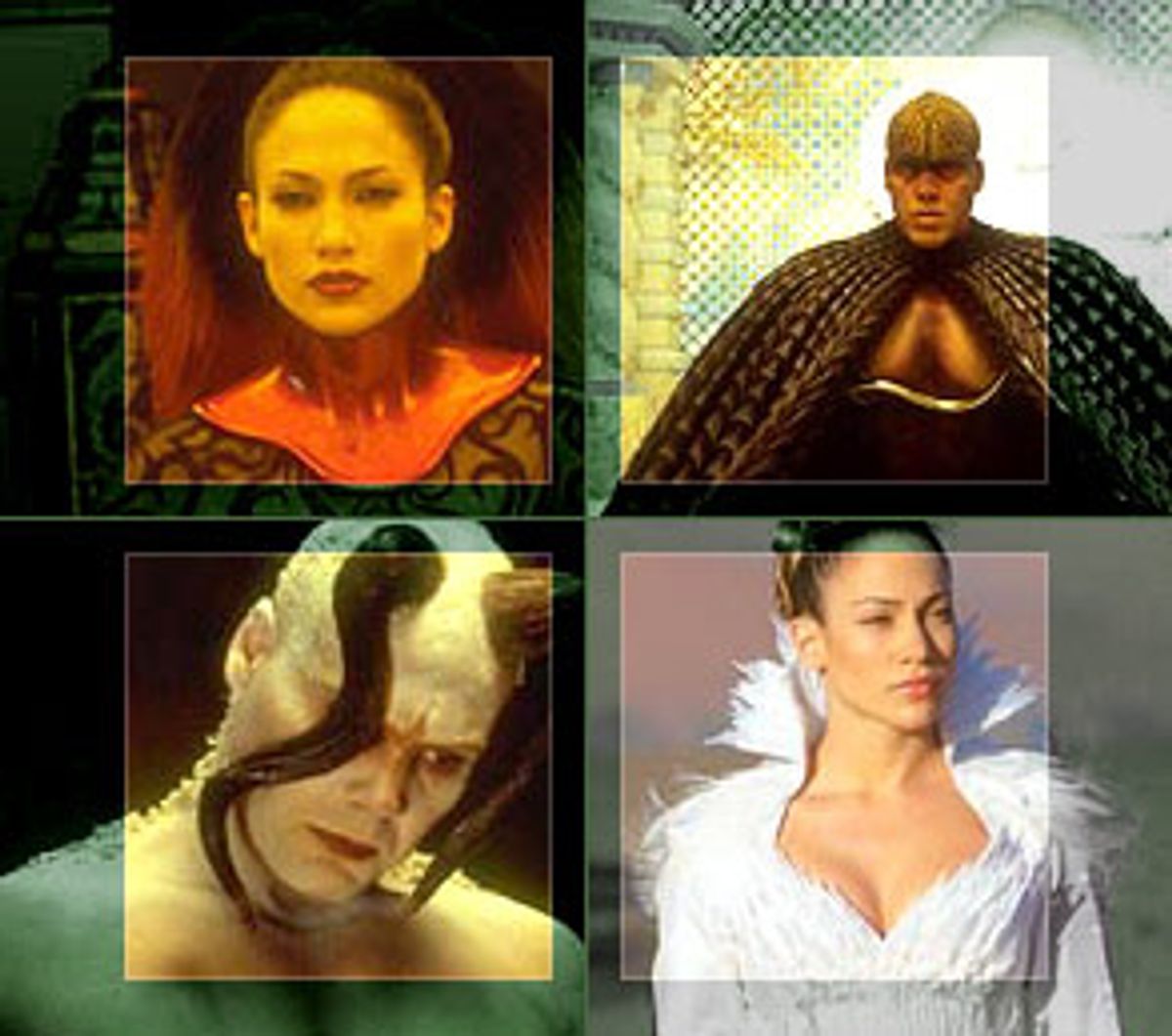

As we jerk and splash through the oversaturated fantasies encountered by therapist Catherine Deane (Jennifer Lopez) while exploring the brain of serial killer Carl Stargher (Vincent D'Onofrio), Singh provides us with an unguided tour of the avant-garde film and visual art styles of the last 40 years. His facility for images is as remarkable as his range of references, and as memorably decadent as the operatic costumes by designer Eiko Ishioka. (Can you still call it Orientalism if the artist is actually Asian?) We go from dazzling screens of abstract animation -- a style of the '50s most famously appropriated in Stanley Kubrick's "2001" -- to the studied, pseudo-mystical iconography of Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky and the gruesome puppetry of the Brothers Quay, with its roots in the sadistic fables of E.T.A. Hoffmann. Then there's the erotic fetish photography of Helmut Newton, not to mention the sliced-and-diced livestock of English artist Damien Hirst and the medieval torture-garden aesthetic popularized by Clive Barker's "Hellraiser."

This is startling, even stunning, stuff; any devotee of stylized eye candy already understands that "The Cell" is a major event. But for all the opulence of its visual display, this movie has no vision. Of course most viewers won't catch most of Singh's references -- I'm sure I missed plenty myself -- but I think the sense that this is essentially a borrowed universe, a kind of pastiche, is unmistakable. As in one of Singh's videos or commercials, the delightful weightless sensation created by his outrageous imagery basically becomes its own reward: the visual equivalent of a crack hit. There are moments in "The Cell" when you'll almost forget that there's an ordinary genre movie going on outside Singh's fantasy world. Although that movie starts briskly and seems to crackle with energy and ideas, it rapidly devolves into standard serial-killer fare, depressingly short on imagination or vivid characterization.

"The Cell" will be compared to lots of other movies, but considered as a whole it doesn't live up to any of them. Unlike, say, "The Matrix" or "Brazil," it offers no coherent social critique or satire. Unlike "Silence of the Lambs" or "Seven," it fails to create and sustain a nightmare voyage into the self where outer and inner worlds eventually merge. Maybe it's tiresome to assume that a video director has no feeling for drama, but Singh certainly seems to care more about individual scenes than the architecture of his narrative. When his characters are in the real world, and not trapped amid tableaux of corpse-like dolls or pursued by androgynous samurai bodybuilders, he frankly seems bored.

Part of the problem here is Lopez, who has always struck me as a sweetie-pie and a knockout, but not an actress. She's able to play a nice girl, such as the friendly shrink who's trying to coax a brain-damaged boy out of his shell early in the film, and when needed she can call upon a kittenish but potent sexuality. But she's totally incapable of conveying anything grave or serious. When she tries to say a line like, "For severe schizophrenics there's no difference between fantasy and reality," she crinkles up her brow and looks sad, like Miss Nevada talking about world hunger, and you immediately stop listening. Anyway, Catherine functions more as a design element in Singh's patterns than a character; she's a wide-eyed Alice, all grown up but still plenty innocent, set adrift in a demonic wonderland.

Mark Protosevich's screenplay for "The Cell" seems to have been concocted by stirring two distinct movies together, without ever quite dissolving the lumps. One is a hunt-the-wacko police procedural in the familiar "Kiss the Lamb Collector" mode, and the other is a high-tech yarn about a dangerous virtual-reality gizmo, ` la "The Lawnmower Man." When we meet Catherine, she's suspended from the ceiling in a form-fitting contraption that looks something like a baseball catcher's chest protector and something like a pile of hot dogs. The machine she's rigged up to -- whose operation is never explained, even in the vaguest terms -- lets her explore the mental universe of Edward (Colton James), the comatose boy.

These placid but subtly troubling scenes in Edward's Sahara-like inner landscape are among the film's best, for my money. As Catherine tries to coax the boy away from the sinister, impish figure he believes has him trapped, we begin to see scraps and fragments of the movie's other story. A serial killer whom the FBI has been hunting in rural Southern California has begun to make mistakes, and rumpled Agent Peter Novak (Vince Vaughn) believes he wants to be caught. We meet Stargher long before Peter does, and some of Singh's intuitive visual connections in this section of the film are eerily inspired.

The sand dunes inside Edward's mind are echoed by those behind the abandoned building where Stargher has built his "cell," a sanitized enclosure where his captive women are fed, cared for and meticulously videotaped -- before being slowly and agonizingly drowned. When Catherine, at home in her apartment (watching very peculiar TV cartoons) asks her kitty if it wants some milk, Singh cuts to Stargher lifting the body of one victim from a bath of milky fluid. We're clearly meant to feel that there's some subterranean link between the empathic Catherine, Edward's isolated realm and Stargher's horrific rituals -- but as with so much else in this frustrating film, the idea is then simply dropped.

I'm sure that Singh and his design team have something in mind by dressing handsome-devil Vaughn in the same suit and the same retro tea-stained tie throughout the entire film, but the character is so vaguely sketched that it seems like an oversight rather than a telling trait. Late in the film, Peter mumbles something to Catherine about his troubled childhood, and she knits her brow and gives him that Miss Nevada look. That's also as close as they get to any action in the real world; when both are inside Stargher's brain, of course, they end up in a kinky Anna and the King fantasy that is the film's Grand Guignol high point (and decidedly not for those with weak stomachs).

Rather clumsily, Protosevich's two stories come crashing together. Stargher is captured, but lies in an irreversible coma, unable to reveal where his latest victim, whose torments we witness in gratuitously ample doses, is held captive. Nothing can be done. A sage doctor shakes his head at Peter, saying, "If there were anything, anything ... " Then his expression changes as he remembers: What about those people with the experimental gizmo made of hot dogs? This is almost as obvious as the earlier moment when Catherine tries to convince her superior (Marianne Jean-Baptiste, the black daughter from "Secrets and Lies") to let her "reverse the feed" and bring Edward into her mind. "We've been over this a hundred times," says the boss meaningfully. "It's too risky." In the dramatic trade, this is known as foreshadowing.

Well, all right. Once Singh has actually gotten Lopez into the trick photography and art-history seminar inside Stargher's mind -- and into those amazing Ishioka outfits -- things are pretty close to all good. Tiresomely, she finds Stargher's personality divided between a wounded child (Miss Nevada looks sad!) and a menacing clown-devil adult. D'Onofrio is a talented actor, and when called upon to fly way over the top (imagine Freddy Krueger as directed by Fellini) he's creepily delicious. But at this point in history all serial-killer parts have gotten pretty much the same: the screwy masochistic piercings, the John-Malkovich-on-downers voice, the rat's-nest hair suggesting a woman's wig.

Could Singh make an actual movie if he had a better script and actors forceful enough to impress their personality on it? Or is he just an empty visual stylist doomed to rattle around in lame genre pictures, in the noxious tradition of Joel Schumacher? Based on this confusing welter of undigested ideas and images, I have no idea. But when Peter finally has to come into Stargher's mind in search of both the trapped Catherine and the missing woman's whereabouts, Singh provides what is undoubtedly the finest cinematic freakout sequence since the peyote trip in "Beavis and Butt-head Do America." Hey, it's been a weak-ass summer at the movies. I'll take it.

Shares