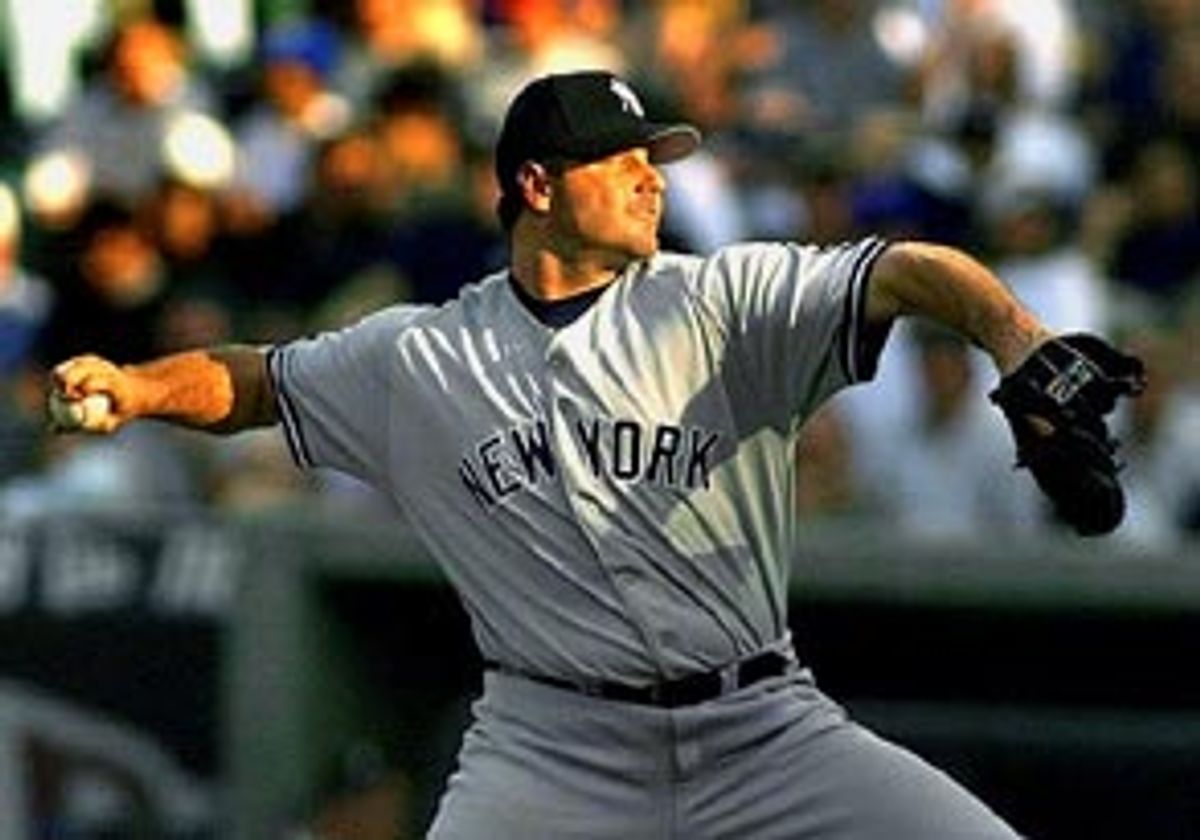

One of the major comebacks of the baseball season is going on right now, and it's happening in the media capital of the country, and the baseball world hasn't caught on. Beat the rush and dig this now: The Rocket is back. How far back hasn't quite been determined yet, but if Roger Clemens is back all the way then the Yankees are back, and not only are they a cinch to win the American League East but they'll be favorites in any post-season game they happen to be in when Clemens starts. And that's whether he's pitching against the man he was traded for, David Wells, or even Pedro Martinez, Randy Johnson or Greg Maddux. Or Sandy Koufax, or Lefty Grove, or Cy Young.

Roger Clemens is the greatest pitcher in baseball history, a fact that has pretty much been obscured over the last two seasons. Let me present the evidence. Clemens has led the league in earned run average, the single most important pitching statistic, six times in 16 seasons. (Since he won't lead the league in ERA this season, make it six times in 17 seasons.) The only pitcher who has won more ERA titles than Clemens is Lefty Grove, considered by many historians to be the best ever. But when Grove was playing in the '20s and '30s he only had to compete against the starting pitchers of eight teams to win those titles, and Clemens, for most of his career, has competed against about twice that many. Grove's career ERA was 3.06; Clemens, as I write this, is at 3.05. Grove, pitching for the great Philadelphia A's teams of Connie Mack for nine of his 17 seasons and backed up by such Hall of Famers as Mickey Cochrane, Al Simmons, Jimmy Foxx and Ted Williams, had a career won-lost percentage of .680. Clemens, pitching mostly for mediocre Red Sox and Toronto teams, has a career .647 won-lost percentage. Whose achievement is greater? Well, the difference between Clemens' won-lost percentage and his teams' is .126 points, the greatest of any starter in baseball history.

So what has Roger Clemens done lately? Well, he was traded to the Yankees from Toronto for Graeme Lloyd, Homer Bush and mostly David Wells. Wells, a regular guy who drinks beer and rides cycles, was popular in New York; Clemens, who is sullen, self-centered and generally boorish with the media, has never been very popular anywhere; and much was made of the Wells trade and how the Yankees got the short end of the deal. They didn't. For one thing, the Yankees plugged the left-handed relief hole created by Lloyd's departure with journeyman Allen Watson. For another, Wells is only nine months younger than Clemens and far less proven. For still another, though Wells has gone 30-14 since leaving New York to Clemens' 24-16, Clemens has actually pitched better, with a 4.28 ERA to Wells' 4.37.

That absolutely no one seems to have noticed this is due in large part to people's expectations. Amazingly enough in a game so much controlled by pitching, the Yankees, the most successful team ever, have never had a candidate for greatest pitcher of all time, and Yankee fans had sky-high expectations that a 14-10 season didn't satisfy. But the letdown over Clemens' performance also had a great deal to do with Clemens himself. When he wasn't sharp he whined and sulked and complained that he had allowed himself to be distracted by base runners, or some such thing. His critics said he didn't have the mentality to pitch for a real winner, that he had become, later in his career, a "defensive" pitcher, afraid to be mean, aggressive, as he was when he pitched for losers. Somewhere along the line, Clemens decided: in effect, no more Mr. Nice Guy. He began to enjoy his work again; he began to pitch inside. It didn't begin on May 7 when he plunked the Mets' Mike Piazza square in the head with a fastball; Clemens had actually begun to pull it together two starts before that. But the Piazza incident made it official: The old Rocket was back. Since then, he has been unbeaten in 10 straight starts, a stretch nearly as long as any in his career, give or take a missed third strike he might have pushed past hitters a couple of years ago.

Clemens denied hitting Piazza deliberately, though he never denied that he wanted to take a hair off his chin. The truth is that Roger Clemens really doesn't give a crap anymore what you think about him, and that's why the New York Yankees will probably be in the World Series this fall.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

I used up all my space last week writing about Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, but I would have liked to add that pound for pound I think jockey Julie Krone, who was inducted into the National Racing Hall of Fame the week before last, was tough enough to have kicked both their butts and Roger Clemens' too. At 4-foot-10 and about 108, Krone rode horses for 19 years and nearly 9,500 races. In one of those in 1993, she was slammed to the turf under a horse and lay there as a second one tumbled over her. It took 14 screws to reassemble her ankle. Six months after the morphine wore off she had both hands broken in another spill. That was her worst year, but in terms of the physical, mental and nonstop verbal abuse she received as the only prominent female jockey, there were no easy ones. And I loved her explanation for what kept her going: "I learned," she said at the induction, "how much I love working out five or six horses in the morning and riding a full card in the afternoon." Imagine how many games Roger Clemens would have won if he enjoyed his work as much.

Shares