There is one, and one reason only, to go see "The Cell" this summer: Jennifer Lopez. I refer not to Jennifer Lopez the actress (for she is a wooden actress indeed), but Jennifer Lopez the icon. Not only is she fashionable -- dressed up in dominatrix leathers, in flowing white-feathered couture, in vinyl collars and silver headpieces and flowing red chiffon -- but she's also a new kind of sci-fi female archetype, taking on serial killers singlehandedly, and winning.

Blockbuster Hollywood sci-fi thrillers have not typically been a place where you'd find sexy, strong heroines beating back demons while dressed in lace gowns. "The Cell" offers this novel sight in abundance; and this summer, Lopez is just one of several female protagonists enthralling the sci-fi crowd. Sexy, strong women and their elaborate costumes are suddenly becoming one of the biggest draws of sci-fi movies, turning a genre that was once primarily about the hormones of 14-year-old boys into transcendent odes to the female powers and finery.

A quick survey of science fiction films reveals a paucity of meaty female roles: In the early days of the genre, most sci-fi leading ladies were granted the role of Love Interest or Saucy Sidekick, but rarely given liberty to actually kick butt. "Soylent Green" went so far as to refer to women as "furniture" (they came with the apartment), and the one enduring sci-fi heroine, Barbarella, still spent more time worrying about getting laid than catching villains.

The '80s changed all that, with the advent of hard-core heroines like Linda Hamilton in the "Terminator" movies or Sigourney Weaver's alien-thwarting Ripley in the "Alien" series. These characters satisfied many a feminist soul as hardened yet maternal figures who blasted their way through films while making no concessions to femininity other than a support bra.

But films have faltered since then. Instead of sexy and powerful female heroines (or villians), we've been treated to an array of namby-pamby female characters. In "Star Wars: The Phantom Menace" Queen Amidala should have inspired a new generation of Princess Leia-like devotion among young girls; instead, the only interesting thing about her was her elaborate gowns, and she wasn't given liberty to strike a cutting figure in combat. (Then again, neither did anyone else in the first episode of the "Star Wars" prequel). Through decades of "Batman" movies, Batgirl barely registered a blip on the radar; Catwoman's sole purpose was to look good in a catsuit. In "The Fifth Element," a conveniently mute Milla Jovovitch crawled about in quasi-bondage gear and found herself in messes.

But a recent spate of sci-fi films has unearthed a more interesting species of heroine, who is both strong and sexy, and doesn't have to dress like a man in order to save the day (although she does, unfortunately, still have to fall back on her male peers in moments of danger). In movies like "The Cell," "The Matrix," and "X-Men," we have a new type of sci-fi heroine: the Fashionable Fatale. She is smart and attractive, lethal yet approachable -- a character women might actually identify with, a character men and yes, the 14-year-old boys who are still some of sci fi's greatest fans, might respect. She's always fabulously dressed, and she's blasting the sci-fi world with an image that fuses sex appeal and power; she is redefining Superwoman.

Science fiction and fantasy action movies have always been the realm of boys, and no wonder: Movies were made for them. They flocked to films filled with muscle-bound male protagonists who could save the world with a flick of their wrist. But it's a vicious circle -- without plausible female superheroines, ones with more depth than your typical virgin or whore caricature, why would girls be interested in sci fi in the first place? Even worse, the lack of believable female superheroes has reaffirmed the notion of men as saviors, women as victims, that we still haven't been able to shake from our heads.

"The Cell" offers the first solo female protagonist we've seen in a major Hollywood sci-fi film for quite some time and, despite the film's (grave) weaknesses, it offers an unusual character in Catherine Deane (Lopez). Deane is a child psychologist whose experimental mind-therapy with a comatose child makes her an unexpected hero when serial killer Carl Stargher is discovered in a coma. In order to discover the location of his last victim, who will rapidly die if she is not released from a watery prison, Deane dons a wired-up red leather bodysuit with muscle-like ribbing, transfers her consciouness into Stargher's head and witnesses the fantasies within.

Here, she finds a surreal landscape of damp concrete labyrinths, desolate fields and graphic biological experiments worthy of Damien Hirst. Stargher's abusive childhood left him schizophrenic and with a violent obsession with water and dolls; Deane must confront his alter egos one by one and subdue them (or save them, as the case may be). She offers an unusual kind of heroine -- one who fights with words, love and weapons -- that should appeal particularly to women who like to think that there's more to warfare than big guns and karate kicks.

In a twist that will also appeal to women, Lopez also is endowed with a couture closet, and the dream sequences become an excuse for us to gape at her taking on the enemy in ever more elaborate get-ups. Deane appears alternately as a badass Diana in black leather bondage gear, caped, with a silver bow and arrow; as a masochistic temptress, chained to a bed and attired in a black lace dress with a lethal-looking silver mask; and finally as a (rather laughable) Virgin Mary, in a red-and-white chiffon wimple with a glowing silver halo. Deane works to soothe the suffering inner child of the psychopath, as well as conquering his evil alter ego with her fierce Diana -- she's part mother, part bitch, capable of using her many womanly faces to take on all of life's little challenges; a multidimensional character reflecting many sides of the female nature.

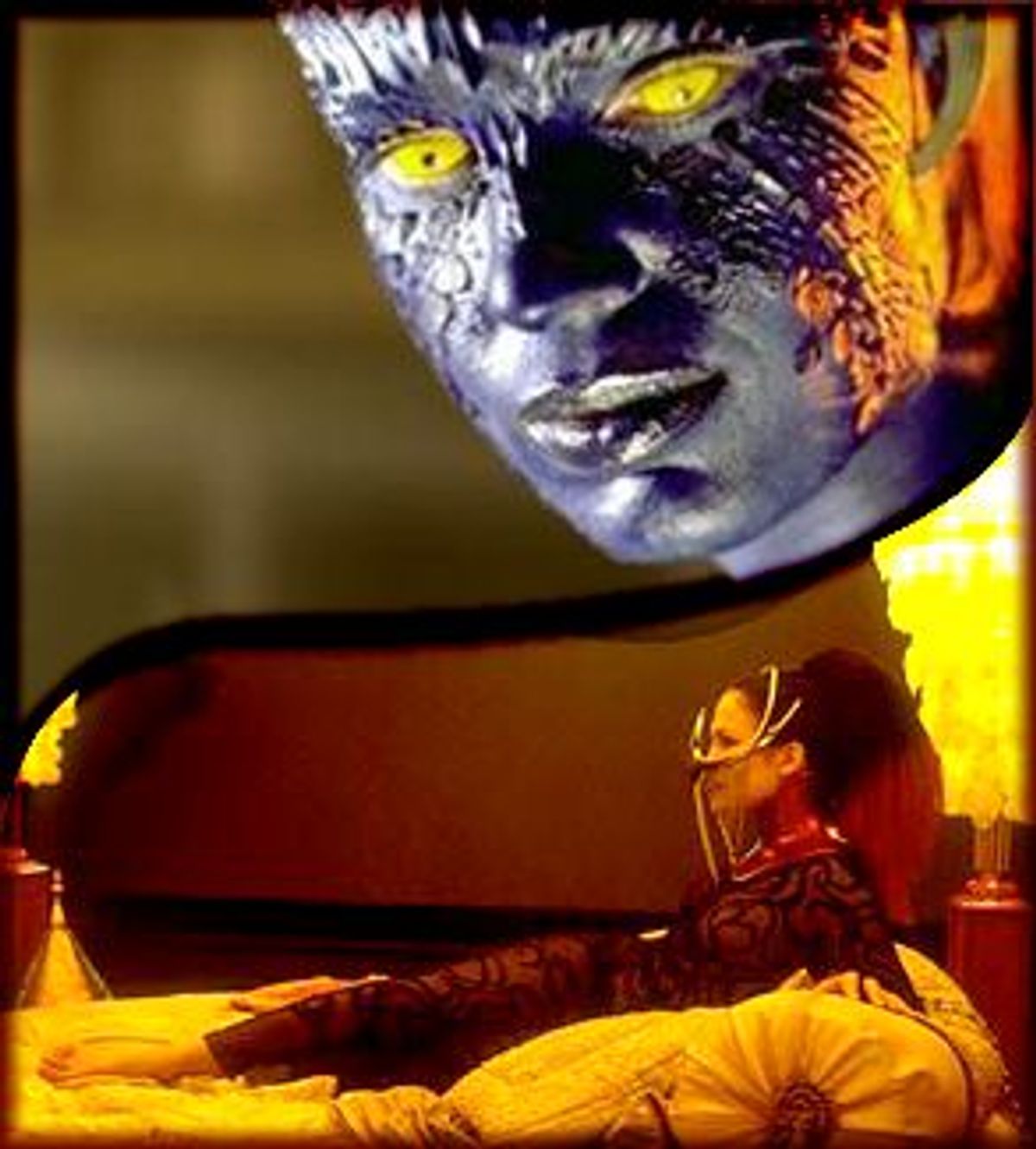

From the opening scene, where she sails across a sea of white sands on a black steed, wearing an enormous dress made of white swan feathers, Lopez is riveting. No sci-fi heroine in movie history has been granted such a luxurious wardrobe, and boy, does she look great. (Stargher's alter egos are also granted over-the-top dress -- grand flowing purple capes, silver face jewelry and Elizabethan collars.) What fun to be able to fight evil and look great doing it; much as we might have loved Ripley, she was a distant heroine, and most girls certainly didn't want to look like her. Unfortunately, Lopez's acting doesn't hold up to her dressing, and her brief scenes of serious fighting action are uninspiring. But it is a start.

This summer's other crowd-pleasing sci-fi thriller, "X-Men," supplies more satisfyingly fierce women. Based on the popular comic book series, the film sets up a war between the X-Men (led by a suave Patrick Stewart) and their enemies (led by a haggard-looking Ian McKellen), all of whom have genetically mutated into super-beings but differ on the question of whether they should just do away with the human race.

Each side has its own selection of impressive mutant females, who are granted their own fancy attire. Most immediately noticeable is Mystique, the shape-shifting bad gal and most devious of all the film's villians; mutely played by supermodel Rebecca Romijn-Stamos, she slithers through the film completely naked but for some blue bodypaint and scales (no doubt fueling a million pubescent wet dreams). With red hair and yellow eyes, she is a force that will be contended with in future "X-Men" sequels; although she is buck naked and admittedly a throwback to male fantasies, she is also the villain who walks away with the movie.

But there's also Storm (Halle Berry), the platinum-haired, white-eyed sexpot who can conjure up lightning storms; she prances about in leather pants and sequined collars (although she, like all the X-Men, gets to wear a sleek black leather catsuit when she goes to fight crime). Her colleague Dr. Jean Grey (Famke Janssen) is endowed with that most womanly of superpowers: the ability to read minds and move objects telepathically. The brains of the bunch, she's also the beauty who captures the hearts of all the men and serves as spokeswoman for all downtrodden mutants.

And then there's Rogue (Anna Paquin), the prodigal and dangerous woman-child, equipped with skin so lethal that one touch could kill a man. Dressed in fashionably gothic gear -- opera-length gloves, long hooded capes and a white streak in the front of her long brown hair -- Rogue is the vampire that all men and mutants fear, with a power than can steal theirs away.

Rogue is a particularly fascinating archetype: a lonely, misunderstood young woman, easily recognizable to anyone who was ever an angst-ridden teenager. Boys will want to date her, to protect her, yet will also be in awe of her power; girls will undoubtably identify with her (some will probably want her wardrobe). She is simultaneously the most approachable, yet most lethal of all the mutants, and a heroine more human than we're used to finding in a sci-fi film. Hopefully, she'll grow into her own powers in future sequels.

Of course, if you're looking for a deeply developed character, science fiction typically isn't the place to find it; and true to form the "X-Men" heroines and villians are essentially comic-book caricatures. But still, these characters -- nurturing-yet-dangerous women, stylishly dressed and sexy without being slutty -- are icons that women can relate to and that men might actually fear. They may be shallow, but they aren't silly or manly or helpless.

There have been a few other examples in the last few years of this kind of heroine. David Cronenberg's "eXistenz," for one, featured an icy Jennifer Jason Leigh as Allegre Gellar, a game programmer dressed in designer togs who defends her precious code with a chilly and deadly precision. And, most memorably, there is Carrie Ann Moss, who played Trinity in last year's blockbuster hit "The Matrix" as a leather-clad warrior fighting alongside Neo (Keanu Reeves) to release the human race from its slavery.

From the first scene of that film, in which she subdues a squad of policemen with karate kicks and leaps across buildings while dressed in skin-tight black PVC, Trinity dominates the screen. Keanu Reeves' eventual entrance to the film as Neo, our hero, feels anticlimactic; Trinity's electric moves, her astoundingly diverse closet of shiny black leather (or is it pleather?) outfits in the most stylish cuts, are more attention-grabbing. She is the ultimate post-feminist heroine: When Neo, upon meeting her, stutters: "I thought you were a man," she coolly replies: "Most men do."

It is a shame that Neo gets to steal all the glory as savior of the human race, while Trinity is doomed to play his enthralled lover. But that's one place where sci fi hasn't changed: heroines rarely get to save the day without the convenient help of an aiding male. In "The Cell," Deane is eventually trapped in Stargher's mind and made his masochistic mistress, where she must be rescued by her CIA sidekick Peter Novak, played by a doughy-looking Vince Vaughn. In "X-Men," it is, again, a male character who ultimately saves the day -- in the form of Wolverine, a half-wild mutant with a soft spot for little Rogue.

But progress is a slow beast. The last decade has given birth to Girl Power and the Power Puff Girls, Courtney Love and the grrrl movement. Catherine Deane, Rogue, Mystique and Trinity are just the first harbingers of what will perhaps be a more gender-friendly sci-fi future. From a more traditional feminist point of view, well-rounded heroines will teach those boys who love sci-fi to appreciate women for more than their bodies and mothering tendencies. And on a lighter note, maybe these icons will spark more interest in sci fi from the female population, much as Tomb Raider's Lara Croft has drawn more girls to the wonders of videogames.

And on the lightest note of all, it's certainly a lot of fun to watch.

Shares