On the third day of the Democratic National Convention last week, Hadassah Lieberman walked out to the Staples Center podium to a sustained, thunderous ovation. The Democrats, with more than twice as many delegates as the Republicans had in Philadelphia, give better ovations, the kind that literally vibrate inside of you. Spread in all directions beneath Hadassah, reaching literally to the rafters, was a waving sea of fresh blue placards sporting her name. It was a heady moment, a degree of personal affirmation that few of us will ever enjoy, and the slender, blond-haired wife of the Democrats' vice presidential nominee appeared appropriately stunned. She stepped back, and when the show of adulation eased slightly, disarmingly exclaimed, "Wow!"

One attends events like these in hopes of glimpsing spontaneity, a moment or two of unscripted reality outside the tidy TV frame. Real politics, the smoke-filled room days of yore, have long since been banished from these quadrennial spectacles, but the candidates, their families, toadies and advisors are all there on display, so there's always a chance you might stumble onto something revealing. Hadassah's "Wow" was a small thing, but it seemed genuine enough. Why wouldn't she recoil momentarily in amazement? It's a cinch that as the wife of Joseph Lieberman, a U.S. senator from Connecticut, she has stood before a goodly number of excited crowds, but nothing like this. This was political enthusiasm turned up a surprising notch ... except, from where I sat in the hall, about 150 feet behind and to her left, I could read the opening lines of Hadassah's prepared speech on the big teleprompter facing her across the crowded hall. The first word of her prepared remarks, printed right there in giant letters on the screen, was, "Wow!"

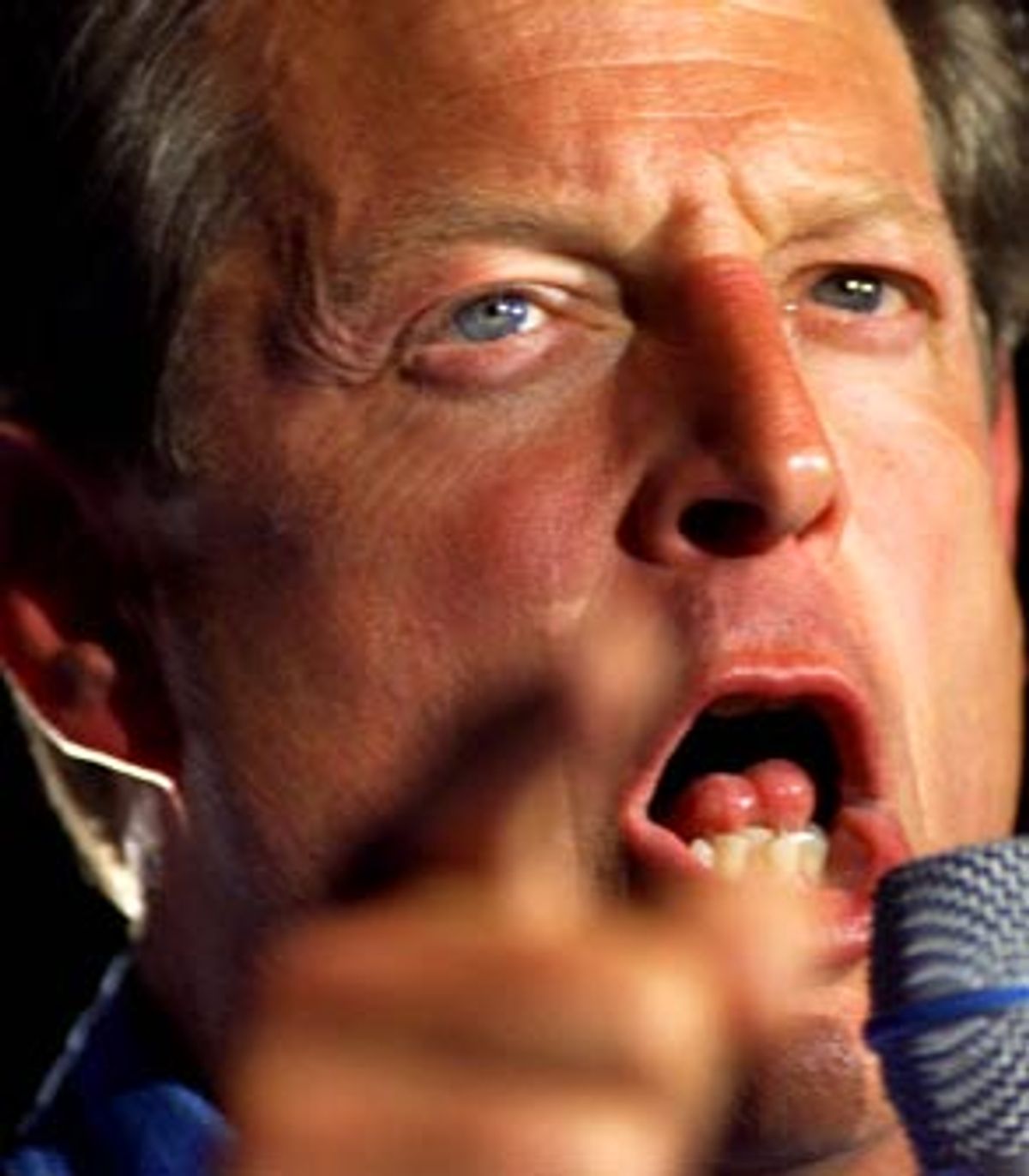

If an event is scripted, can it still be real? This one was no different than a scene in a movie, planned, written and (certainly in Hadassah's case) rehearsed. When Al Gore planted that earthy, open-mouthed kiss on Tipper as he stepped on stage the next evening, practically knocking her over backwards, we can only assume that was calculated, too. After all, we have charged poor Al with the Zen-like challenge of striving not to strive, of being clever enough not to appear too bright, of being morally upright enough to counter the scandalous libido of his former ticket mate without seeming too "stiff."

The kiss was clearly calculated, yet by all accounts they are an especially close, loving couple. No doubt Hadassah found the ovation stirring, just as she and her speechwriter anticipated it, so maybe "Wow!" would have slipped from her lips even if her speechwriter hadn't put it there for her. She did actually say "Wow!" twice, so maybe one of them was genuine. We will never know.

I suspect this degree of choreography is behind what most Americans find distasteful about politics. I'm willing to accept that the scripts at both conventions, the Republican show in Philadelphia and this one in Los Angeles, were designed to reveal the truth, or parts of it, but anything that manipulative hardly inspires trust. When there is no trace of anything genuine in a campaign, the public rightly grows wary. If the script called in advance for an expression of surprise or of supposedly spontaneous affection, even if there is something real behind it, how are we to know?

I have to report that the "realest" moment of the whole blatherfest for me was something I saw on screen. In a stroke of surprising originality (perhaps born of desperation) the Gore campaign invited film director Spike Jonze to make a short documentary film. Gore had evidently liked Jonze's delightfully bizarre "Being John Malkovich," and chose to offer him an opportunity to film the Gore family at their vacation home in North Carolina and various other places earlier this summer. It continued a tradition that began during the first Clinton/Gore campaign, when filmmakers trailed them for months making the fascinating documentary "The War Room." In Gore's case, the idea wasn't to capture the mechanics of the campaign, but the flesh-and-blood Al Gore. As Al noted in the film, the vice president is the cardboard cutout on stage behind the president at official functions, so what makes him think he's qualified to be president? In contrast to the slick, somewhat smarmy video shot at George W. Bush's ranch by an ad agency and shown at the GOP Convention (think of a standard 30-second TV commercial drawn out over 10 minutes), Jonze shot a stylistically raw slice of life. It did more in 10 minutes to break down Gore's famous "stiffness" than an army of campaign consultants have been able to do. We see the candidate at the dinner table being made fun of, lovingly, by his grown children, giving a tour of the family's photo gallery (which reflects Tipper's evident wit), playing with his baby grandson and, in one scene, displaying a marvelous deadpan as he jokingly complains about his wife's habit of going barefoot.

"It's ruining my image," he says, looking hilariously doleful.

"That's my job," says the chipper Tipper.

This was all by design, too, of course, but it worked. The warmth and normality of the Gore family at ease cannot have been faked, and the courage to allow an offbeat filmmaker like Jonze the freedom to record it shows a confidence surprising in a candidate trailing in the polls at the time and for whom one slip of the tongue between now and November could relegate him forever to footnote status, the gray land inhabited by vice presidents who never assume the highest office.

Gore took a big step at this convention and, looking back over the whole messy pageant, I'm impressed. He has closed the gap in the polls between himself and George W. Bush, and unveiled a new populist liberal image that both suits him and well positions him for the final months of the campaign. In the days since the convention ended, Fighting Al, whose campaign seemed moribund a week ago, now seems to be the candidate of purpose and energy. During the first three days of the convention, most pundits I heard and read were proclaiming it a disaster. Clinton won't get off the stage, they said, and what was that Kennedy day all about? But taken as a whole, the Gore convention managed to shoo the president gracefully off center stage while laying claim to the legacy of his very popular policies; it introduced Gore as a devoted father and sexually grounded husband (that's what that sloppy kiss was all about); and it reinvented him as a by-gosh fighting Tennessee populist more in the image of his father than Bill Clinton.

This was the smartest move of all. Somebody in the Gore camp realized that the moderate, centrist path charted so effectively by Clinton contributed to his image as a man who stood for nothing, who moved according to favorable political winds. Bush played on this at his convention, selling himself as the candidate of principle who didn't need polls to tell him the right thing to do. By returning to the Democrats' more liberal roots (that's what Kennedy day was all about), Gore contrasted his policy differences with W., while defining himself more clearly to voters. He lambasted the status quo like somebody who didn't have anything to do with it: The verb "to fight" appears 22 times in his speech.

But that was Al's challenge precisely. He is charged with running both for and against the Clinton presidency at the same time. And damned if he hasn't pulled it off.

Jonze's film countered the most telling criticism Bush leveled during the GOP convention. In his acceptance speech, the Texas governor said he wouldn't be borrowing any clothes in an effort to win the White House. It was a reference to the great gear-shifting in Al's primary campaign after Bill Bradley mounted an unexpectedly strong challenge in New Hampshire. Gore shifted his campaign headquarters from Washington to Nashville, hired himself a few new image consultants who traded in his dark blue suits for earth-toned weekend-wear. A small move, perhaps, but it spoke of something more than desperation. It suggested that Big Al was willing to do anything to get elected president. If he changed his wardrobe and hair style, if he suddenly became a champion of campaign finance reform (after breaking all records -- if not a few laws -- building his own campaign chest), it suggested there was no there there, that the candidate was all want and no agenda. Hidden in that accusation was a link to the thing that voters dislike most about the Clintons: their apparent willingness to swallow any indignity, reverse themselves on any issue, in order to win public office. So Gore needed to show some constancy in his character, some reality behind the cardboard cutout, and how better than to invite the world right into his living room, to see him with his feet up, without TV makeup, with no script, the butt of his offspring's affectionate ridicule?

All of which effectively countered the Democrats' biggest problem, which is Slick Willy's aforementioned slick willy. To that end, I suspect the supposed writhing of the Gore camp over the long weekend before the convention, and then through the Hillary and Bill Show Monday night, were calculated to strike just the right balance. There would be no denying the president his long weekend goodbye, basking in the affection of a town he has made his own. His thin veneer of smarmy populism plays perfectly in Tinseltown, the only place in America where multimillionaires still think of themselves as "the little people." Hollywood is also the world's primary bastion and purveyor of liberal social values, the capital of live-and-let-live (provided you don't try to smoke in a public place). So even though the demographics of Westwood, Hollywood and Santa Monica scream Republican, the place is as Democratic as the Kennedys' living room. Jeffrey Katzenberg, one of the reigning moguls, recoiled when I asked him why he wasn't a Republican. I confronted him, a short, tan, balding man in a hurry, as he was departing a fundraising luncheon he sponsored for Democratic women congressional candidates at Regency Studios in West Hollywood. Hillary had just given a short speech.

"This is one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in America, can you tell me why it is so Democratic?" I asked Katzenberg, who didn't stop walking.

"No," he said, and grinned that why me? grin that all celebrities have and glanced around quickly to locate studio security.

"OK, then why are you a Democrat?"

"I can't speak for all of Hollywood, but for me, when I look around this room, I see women who have mounted campaigns for things like improving education, gun control, healthcare and for protecting a woman's reproductive rights," he said. "These are issues I believe in and support, and these are the people I want leading our country."

The Clintons have learned to work this rare vein of liberal gold in the California hills.

Dan Jinks, co-producer of last year's Oscar-winning "American Beauty," helped host with his filmmaking partner Bruce Cohen a fundraising luncheon for Hillary several months ago, even though he had never met her before.

"She called me one day to tell me how much she and the president liked our movie," Jinks said. He and Cohen were flattered, and perhaps a bit surprised, given that the movie depicts a man who lusts after his teenage daughter's girlfriend (but, significantly, doesn't cheat on his wife, who does cheat on him) and is murdered by the closeted "don't ask-don't tell" gay colonel who lives next door. But, hey, the president likes your movie, you don't complain. A few weeks later, the pitch followed: Would you and Mr. Cohen consider holding a lunch for Hillary the next time she's out your way?

Fashionably decadent Hollywood would also be the last place to hold the president's indiscretions against him. The payoff for the movie stars, directors and producers, of course, is access to power. It is significant to note that in the past, celebrities courted power. Now it's the other way around. The Clintons have nurtured the loyalty of their Hollywood FOBs (Friends of Bill) by inviting a steady stream of them east for state banquets and sleepovers. Whoopi Goldberg gushed that she had met "kings and queens," and that the White House help didn't even check her luggage for purloined silverware and souvenirs when she left. Actress Alfrie Woodard was epic in her praise, calling Clinton "a righteous brother, not in the holy way, necessarily [we wouldn't expect], but in that brother-man way, that one-with-the-people kind of way, coming from them, moving among them ..." No one was more grateful for this access than John Travolta, who gave a remarkably accurate and affectionate portrayal of Clinton in "Primary Colors." At a party hosted by primo FOB Barbra Streisand, the diva produced a pedestrian prose anthem of tribute: "Bill Clinton is our president, my president, and these have been the best eight years of our lives ... What will we miss? What endeared you to us? I can only speak for myself. If I were ever in Washington and asked you for directions, you'd think about it, and you'd put me on the right path ... If I were hungry, you'd sit down and eat a cheeseburger with me, and you wouldn't hold the fries."

The idea was to let the president hog the spotlight for a few well-earned days (with the Gore camp whining off the record), and then clear him out for the real business. I was watching on television across the street from the Staples Center Monday night when the president gave his swan song, another performance smooth enough to charm a dog off raw meat. It was preceded by that odd hallway sequence, with Clinton striding purposefully up one long hallway, turning, striding up another, turning, striding up another. The sequence, I learned later, was designed to have a long list of Clinton administration accomplishments scrolling across screen while the president hiked, the length of his entrance drawn out by the sheer magnitude of his success, but some of the networks, including the one I was watching, decided not to show the text on-screen.

There were those who complained that Clinton's speech, while typically good, was too long and too much about him. I suspect this was more calculated leakage by the Gore camp, but I think it's only fair that we allow presidents to assume credit for these things, because we also blame them when times are not so good. Kurt Schmoke, the former mayor of Baltimore, once told me that while most people think of the mayor as the man behind the wheel of the city bus, in reality it is more like hitching a ride on the bus's back bumper. If it reels out of control, the best you can do is hang on and signal frantically for help -- because it's gonna go where it's gonna go.

What you can control, at least to some extent, are images and perceptions. Which is why hosting an official party event at the Playboy Mansion was a bad idea. California Rep. Loretta Sanchez's plans to hold a major Hispanic fundraiser at the mansion provided Fighting Al a perfect opportunity to advertise how things were going to be different now. Gore's forces went so far as to threaten to revoke Sanchez's invitation to speak at the convention if she didn't back down, which she did -- and then withdrew herself from the convention's speaking agenda in a fit of pique, thereby sparing everyone 15 more minutes of forgettable rhetoric.

Hugh Hefner's fantasyland in Westwood has recently been restored to hipness, but, for obvious reasons, hipness is one trait Gore cannot afford just now. For all its claims to licentiousness, the mansion throws rather tame parties. I made my second trip up the hill to Hef's sculpted acres on Saturday night for a preconvention party there, and the event had a kind of manufactured feel -- indeed, the mansion is a kind of convention hall, hosting parties so regularly that it maintains its own shuttle buses to move guests from the parking lot at UCLA up to its neo-Gothic grounds. There were two open bars and a band in the big tent out back that nobody was paying attention to. The crowd confined itself for the most part to the patio in back, around the second open bar, and trips into the grotto were just to tour the place, as one might inspect the Lincoln bedroom. Bill Maher and Arianna Huffington were there, Bryant Gumbel with a pretty blond, Patrick Cadell, the Democratic pollster, Christie Hefner, the cynical brains behind the operation and a horde of normal pop-eyed media types like myself. I wound up playing pool in the game room, which actually had Pac-Man among the collection of pinball and video games. Remember Pac-Man? I went looking for Pong, that most ancient of video games and by now, I would think, a real collectors' item. I didn't find one.

The truth is that the Playboy mansion is like a relic of a bygone era, a piece of 1950s Americana preserved, as it were, in amber. Hef was there, but not in pajamas, and not with the blond bombshell twins he has been touring with of late. Hawk-nosed Hugh looks old but well-maintained, holding forth on his philosophy of sexual freedom 20 years into the AIDS era. I'm sorry, but there is something quaint about packaging demure, air-brushed pulchritude in a world where you can watch people copulating with animals on your home computer with just a few clicks of a mouse. Just last night I was flipping channels and came across a naked man and woman having sex on a two-way swing suspended from the ceiling in the clever prime-time HBO series "Sex and the City." One thing Playboy is not any more is risqui.

Playmates today look like Barbies with carefully groomed patches of pubic hair. Hefner's supposed four-way relationship at the mansion sounds to me like a form of Hell, as though Satan had devised the perfect torture for Hef's past sins -- revenge of the bimbos! -- condemning him to live as a parody of his youthful self, the flamboyant septuagenarian playboy of the '60s enslaved by the demands of four -- count 'em! -- live-in playmates who, I suspect, put a greater strain on his credit cards than his Viagra-assisted libido. My suspicion is that Hef was in on this mini-scandal all along. It made some great publicity for Playboy, which must struggle nowadays to be racy, and it allowed Fighting Al to flex his rectitude.

The protesters were back in about the same force as we saw in Philadelphia, and with the same painful lack of presence. As I was walking out of Staples Center one night, tired after treading water through a long day of windy rhetoric, a young woman pleaded with me, "Don't just walk past, I've come all this way to talk to you." I stopped. She was advocating an end to the death penalty. I told her I completely agreed with her and marched off to dinner. Maybe it's just me, but it seems to me these traveling bands of protesters are acting out some script that no longer has any relevance. Once again, they joined forces for so many causes that any message they hoped to convey was completely lost. In a world where opinions are repressed, where one cannot publish opposing views or advocate for radical change, street protests are a way of sending a message that cannot be transmitted any other way. In our world, I'm afraid they have become just a nuisance.

Tuesday was Kennedy day. It turns out that John F. Kennedy and his siblings had enough children to fight off all the ravages of drugs, murder, rape and that black cloud of tragedy that seems their unique inheritance. Four Kennedys spoke: Robert F. Kennedy Jr., now an environmental lawyer; Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, the lieutenant governor of Maryland; Caroline Kennedy Schlossberg; and, of course, Uncle Teddy, who seems to have lost his oratorical power. There were more Kennedys in the wings, Maria Shriver and Rhode Island Rep. Patrick Kennedy (said to be the real comer of the brood). Caroline emerged on stage to the show tune "Camelot," and looked fragile and stiff enough to break under the weight of so much affection. She hurried through a sweet little speech, thanking the nation for caring so much while her eyes seemed to be screaming Please leave us alone! Joseph Lieberman gave a very relaxed, agreeable speech the following night. As the first Jewish candidate for such high office in the country's history, he could consider his job pretty much over the day Fighting Al asked him to join the ticket. A man of impeccable morals and dignity, he is a dose of anti-Clinton whose sometimes heretical independence in the Senate -- supporting school voucher experiments, for instance, and advocating reforms of affirmative action -- are to be devoutly overlooked in the interests of winning the White House. I talked to a group of public school teachers in the hall, those most institutionally opposed to school vouchers, and they had already forgiven him. Barbara Kerr, a first-grade teacher at Woodcrest Elementary School in Southern California, said she didn't like Lieberman's position on the voucher issue, but felt he wouldn't dare continue to advocate such a thing while on the ticket with Al Gore.

"He won't support it anymore," said Kerr confidently. "I think he's gonna be just fine. I'm a teacher and I believe I could teach him in about a minute and a half why vouchers are a bad idea."

For all the high-blown rhetoric of the political convention, Kerr seems to have grasped the essential fact that parties are essentially cynical constructs. They are alliances of interests to acquire power. Ralph Nader complains that the Republicans and Democrats are really the same, that they both represent established shades of corporate power with different positions on abortion. I think he's wrong. One look around the multicolored skin tones inside the Staples Center, at the enormous broad back of bearded Iowa delegate Wilbur Wilson, a giant in a black, sleeveless United Steelworkers Association of America T-shirt, and there's no mistaking it for the GOP convention. The parties represent two different power alliances. They ignore issues that lack a broad consensus following, such as abandoning a fruitless war against drugs in favor of educational efforts and medical treatment for addicts, or doing away with the death penalty, because such issues hurt them more than help them on election day. But they align themselves very differently around some of the biggest issues of the day.

Fighting Al's biggest success Thursday night was to clearly illuminate those differences. He would not "waste" the budget surplus by giving it back to taxpayers (an average windfall, he argued, of 62 cents a week), and would instead use it to shore up Social Security. He left little doubt that he would fight harder than Bush to protect the environment, a woman's reproductive rights and to expand healthcare. He promised to make a campaign finance reform bill the first one he would send to Congress. There are real divisions in the country over these issues, and Gore staked out his side of the field very cleanly.

He also laid claim to being a candidate of more substance than Bush. Just as he was serving in Vietnam when the future Republican candidate was flying jets for the Texas Air National Guard, he was making decisions in the White House when W. was making personnel moves for the Texas Rangers baseball club.

If Al Gore wins this thing, I will always remember his entrance Thursday night. The Secret Service had cleared an aisle on the packed Staples Center floor, and at the appointed moment instead of walking out from backstage, Fighting Al emerged from the crowd, the very picture of a man of the people. He strutted up the aisle slapping five with both hands, stopping to pat the heads of children. As he passed me he seemed about ready to bust with patriotic pride and humble appreciation for so much plain unsolicited goodwill. The hall rocked to the rafters with cheers, with a great stirred unanimity of purpose, and I thought, damned if he hasn't pulled it off!

It may be theater, but it's great theater. Now I'm waiting for the debates.

Shares