Ernest Rutherford once sneered that botany was more like stamp collecting than real science. The celebrated early 20th century physicist was referring to the field's lack of mathematical rigor, its frequent unsuitability for experimental research, its openness to amateur enthusiasts.

Before the discovery of DNA, which converted all of biology into the hot zone of science, botanists could indeed seem like nerdy kin to stamp collectors, birdwatchers and hoarders of 300 varieties of salt and pepper shakers. Their passion was not for growing plants, but for finding, identifying and categorizing them. They went out into the field and got excited, for god's sake, about grasses and sedges and such.

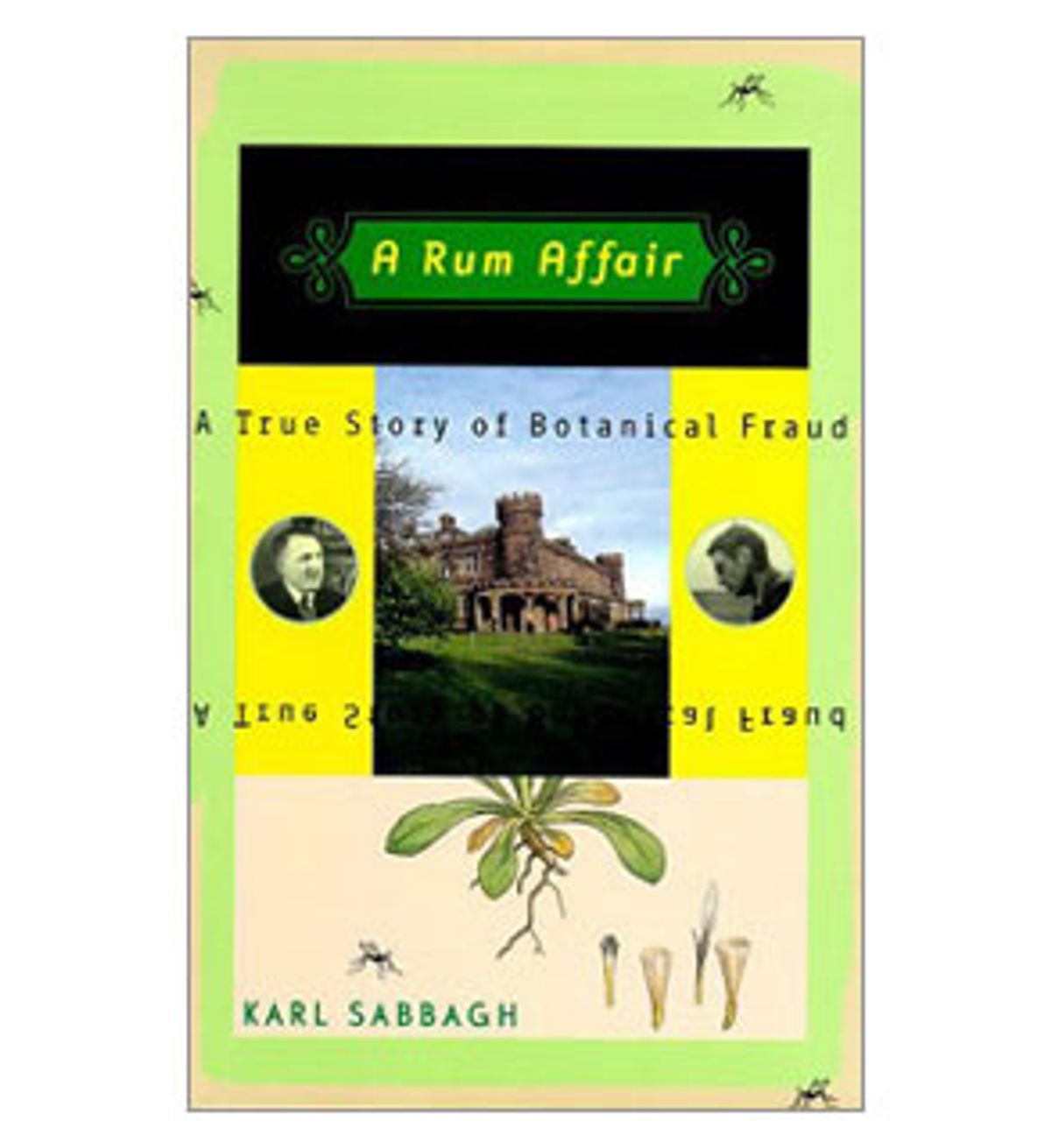

In this seemingly unpromising terrain, Karl Sabbagh, an English author and producer of science programs for BBC Television, has unearthed an intriguing story about the politics of science. It's a saga with dueling protagonists, outraged charges and countercharges, motivations shrouded in mystery. Yet it's a saga without a proper conclusion, ebbing away in very low-key, very British understatement. "A Rum Affair," for sure, as the Brits like to say about odd or strange events.

The time is 1948. In one corner is John Heslop Harrison, an ironworker's son risen to a professorship in botany at Newcastle University and membership in the Royal Society, Britain's equivalent of our National Academy of Sciences. His young accuser, John Raven, is a well-connected scion of Cambridge. He is the son of a don in theology and a graduate and tutor in classics himself. Yet he is also an accomplished amateur botanical scholar.

Heslop Harrison has gained prominence as an authority on the flora of the Hebrides, the islands off the northwest coast of Scotland. A man of immense learning and field experience, he is also a brusque personality, dogmatic in his views and hostile to anyone who dares question him. Which is precisely what Raven does. Willing to stand up for his beliefs, no matter how unpopular -- he was a conscientious objector during World War II -- Raven has come to believe that Heslop Harrison is a liar. For Harrison claims to have discovered on the Isle of Rhum (later called Rum) rare plants, including some of those grasses and sedges previously thought not to be indigenous to the Hebrides. Not a big deal, one might think, except that the claim is a key link in a more far-reaching hypothesis that the islands, unlike the rest of Scotland, somehow escaped the last Ice Age 10,000 years ago.

Sabbagh's method is to follow his young hero as he stalks esoteric plants and the villainous Harrison. Roadblocks are everywhere. Rhum is isolated and owned by one Lady Bullough, though it's guarded by Heslop Harrison as though it were his private domain. Raven manipulates his way onto the island, cannot find any sign of the plants, retreats to Cambridge, writes a scathing report for university authorities charging that the great scholar has imported and planted the specimens himself. Simply put, Heslop Harrison's breakthrough discoveries are fake.

But, alas, Raven's revelations go nowhere. Harrison suffers no public exposure, no loss of job. Despite never again trusting the man's work, no one in the British botanical establishment wants to make any waves. And besides, the evidence of fraud isn't foolproof. Raven's impossible task has been to prove a negative: that on Rhum's 40 square miles the specimens do not exist.

Thus "A Rum Affair" becomes a scientific detective tale. Like Susan Orlean's "The Orchid Thief," it chronicles skullduggery among floraphiles, though without that New Yorker writer's smoothly witty delivery. Like Simon Winchester's "The Professor and the Madman," it portrays an intellectual odd couple in a British setting, though without that book's boffo drama of murder and madness.

Though we keep expecting Sabbagh to surprise us by uncovering evidence that Heslop Harrison was innocent after all -- in dramatic terms, he's too much the stock villain, a despot as department head at Newcastle and a nasty, officious opponent for Raven -- the author remains convinced of his wrongdoing. In British field guides today, he notes, Heslop Harrison's "finds" are subtly dismissed.

Sabbagh tries to put his malefactor in context by examining scientific fraud elsewhere, but, oddly enough, never mentions the case that rocked the American molecular biology establishment in the '90s. What's most startling is the contrast. A public accusation by a young post-doc that her boss at MIT had faked data, the involvement of Nobel Prize winner David Baltimore, congressional hearings and the accused's eventual exoneration -- all of this would have been anathema among Britain's tweedy gentlemen of the '40s.

In the Heslop Harrison case, the most puzzling aspect is the apparent lack of motive. Already at the summit of his profession, he risked his good name for a few more morsels of fame. In the end, Sabbagh's research indicates that the man was probably a congenital liar. Even in his ventures into entomology, he couldn't control his penchant for extravagant claims. His alleged sightings on Rhum of the Large Blue butterfly and several species of water beetles have never been duplicated.

Then there's the matter of Heslop Harrison's address. Throughout most of his career, he listed his as "Gavarnie, The Avenue, Birtley." He bestowed a pretentious name, Gavarnie, on his home. So far, so good. It's the English way. Yet he didn't in fact live on The Avenue, the most imposing street in his Scottish village, but on an adjoining, less impressive road. You could chalk this aberration up to class resentment against people who began life with more advantages. Or you could simply call it pathology.

Shares