No one ever expected Sean Dix -- the gently gruff, hardworking New York kid turned quirky inventor -- to wind up in jail this summer, especially not for sending a death threat to one of the world's most powerful men.

Since 1995, the ambitious 32-year-old has put his life's savings of $65,000 into manufacturing and selling something he calls floss rings. Floss rings, for the uninitiated, are plastic rings that one ties to the ends of a length of dental floss. Dix anticipated that the invention would return his investment and then some, $1.99 at a time.

A psoriasis sufferer, he developed the idea after years of painful flossing sessions; although it takes a little effort to tie the floss onto the rings, the small, plastic dental aids sit much more comfortably around sensitive fingers than raw floss. Arthritis sufferers can also find solace in floss rings.

Dix watched as his affordable product won favorable reviews from the press, including Bloomberg Radio, and got picked up, gradually, by more and more major department stores and pharmacies. He grew even more hopeful when a 1996 Beutel study found that using the rings while flossing can lead to the removal of as much as 23.8 percent more plaque, and when the Museum of Dentistry in Baltimore added the rings to its "Dentistry in Transformation" section.

So Dix was flying high when CNN called to say it was running a news piece on his floss rings. He spent nearly two months providing the network with information to illuminate the virtues of his product. The CNN crew came into his home and his company's office in New York multiple times. Dix told everyone he knew in media and venture capital about the airing of the show.

He even called and thanked the CNN segment's producer, Linda Djerejian. And in her response, Dix saw his world -- and possibly his mental health -- begin to crumble.

"She said to me, 'Well you might not want to thank me yet. You may not like the piece,'" Dix remembers. "I didn't quite understand what she was getting at. I couldn't let myself face [it] because the product was getting such wonderful reviews. But I filed away her statement in my mind." (Djerejian was out of town and unreachable for comment at the time this article was written.)

At 9 p.m. on June 12, 1996, Dix enthusiastically turned on CNN's "The World Today." He sat in disbelief as he watched an eight-minute humor segment, featuring two dismissive assessments from dentists, Johnson & Johnson's decision to not back his rings and, worst of all, fluff TV's reliable minimum of 18 sorry puns: "Sean Dix really put his money where his mouth is," etc.

With his first patented invention the butt of a televised bad joke, Dix's characteristic grin turned into something of a cringe.

The national sales team of 12 at Dix Preventive Products and Dix's most generous investors didn't find the segment too funny, either. Dix says they all bailed within weeks of the first airing of the show.

"Before the airing of the piece, I was about to invest $100,000 in the rings, and was on my way to raising another million," says Peter Lusk, a venture capitalist. "But due to the embarrassingly negative and trivializing tone of the CNN article, I found it very difficult to go back to my contacts -- whom I had alerted to the show -- for potential investment."

Dix is unusually determined and resilient, according to those who know him. "Sean always had a smile on his face," says Tony Chirinian, who worked with Dix in the jewelry business for 10 years. "He is a fair, honest, determined guy that couldn't hurt a soul."

From the look of the sparse one-and-a-half-bedroom apartment Dix and his brother grew up in, he came from an average -- but struggling -- American family, and was committed to creating a better life for himself. "Sean was willing to work for it to no end," says Chirinian. "Even as he watched his life fall apart, Sean kept trying to stay upbeat," he says.

At least at first.

Dix managed to persuade one of the dental specialists who had appeared on the show, Dr. George Reskakis, to reevaluate the flossing aid and then to put his second, kinder opinion in writing.

"I figured, 'What do I have to lose,'" Reskakis says. "Sean was so upset, so I took another look and wrote a more complete assessment." The dentist admits that at the time of the CNN taping, he wasn't given a chance to read the directions before using the product, and that his "initial criticism may have been premature."

Dix began to feel that a conspiracy may have been at hand: Perhaps CNN intentionally denied the dentists time to learn proper use of the rings. Perhaps it was all part of a big business plan to squash the little guy.

After all, the worldwide director of licensing and acquisitions at Johnson & Johnson's Oral Care and Wound Care Franchises in the Consumer Group, Brian Bootel, had said in a letter to Dix: "It is quite conceivable to expect that as many as ten to twenty million U.S. consumers could embrace the product line ... This penetration equates to a U.S. market potential of 50 million dollars to 100 million dollars." Eventually, though, J&J decided not to go with the rings. Is the company waiting for Dix's patent to expire?

Dix is sure of it. "The only reason that CNN would run a hatchet job on such a viable product would be as a favor to Johnson & Johnson," Dix insists. J&J has been advertising on CNN at least since 1996.

But doesn't TV just run fluff for fluff's sake sometimes?

"Yes, but there's nothing humorous about floss rings," Dix declares. "They had to go out of their way -- not give the dentists time to read the instructions -- to make floss rings funny."

Armed with the letter from the dentist, Dix called CNN numerous times over the following two years, begging it to run another piece on the product. CNN journalist Jeanne Moos, who is a patient of Reskakis', stated in a letter to Dix that "we didn't influence [the dentists] in any way."

"Sean, I'm sorry about this," she said. "Getting press is a double-edged sword. And I must tell you, I was fairly gentle in choosing what comments from the dentists and how much of their comments to use. They basically had nothing complimentary to say ... I really don't know what you want me to say. I'm certainly in no position to give advice on merchandising your floss rings ... Now I better get back to work." (Moos was out of town and unreachable for comment at the time this article was written.)

In 1998, CNN finally responded to Dix's demands, promising that if he sent his claims and requests in writing to CNN's headquarters in Atlanta, Ted Turner himself would review the case. Dix sent the package. CNN said it didn't receive it. He sent it again. Still no sign of it.

"So I said to myself, fine, I'm going to make sure you get it!" Dix recalls.

He proceeded to fax his documents 6,000 times over the next four days, jamming up the network's communications equipment for the week.

He didn't get his desired response, but he did get away with the tactic at first. CNN staff saw only one discernible name and number on the pages: the letterhead of the dentist who had taken the time to reassess Dix's rings. "They called and ordered me to cease and desist," says Reskakis. "I called Sean for an explanation and he yelled at me."

A few months later, Dix finally got a response to his obsessive faxing and phone calling. Two men from the FBI came knocking on Dix's door and informed him that his behavior was considered harassment across state borders and that he had therefore committed a felony. He got off with a warning.

But Dix remained committed to having CNN take responsibility for, as he believed, ruining his life.

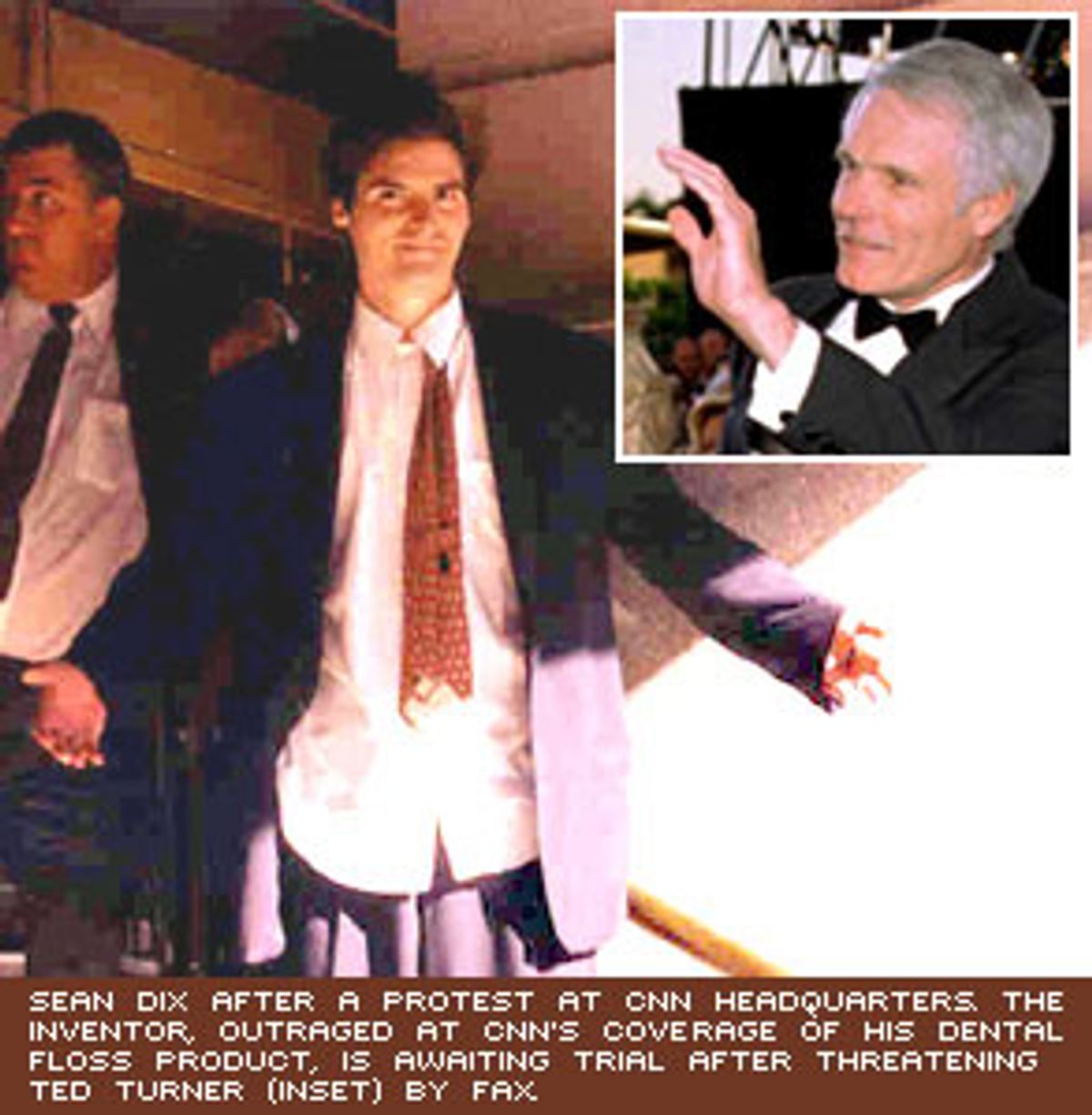

A year after the FBI warning, Dix protested in front of the CNN building with a megaphone and a poster declaring that "CNN and Johnson & Johnson Conspire Against Dix." In a scuffle with security, Dix was thrown down a flight of stairs and was arrested and held for 24 hours.

Ignored, humiliated and in financial straits, Dix launched a more militant pursuit of his American dream.

"I felt like I pushed the envelope so many times -- so one day I said that I don't think anything short of a death threat will make CNN staff look and see what they did to me. I mean, shows like the one they did on me can make people go off the deep end!"

Indeed. In April, Dix faxed a letter that stated, "I am now telling you that if you do not attempt to make restitution I will attempt to kill Ted Turner, and if he is unreachable in his ivory tower, then I only need kill one CNN employee and it will be on your hands."

The police showed up the next day, and Dix was taken away in handcuffs.

"But I was just trying to get CNN's attention," says Dix, who has no prior record of mental illness, and who refuses to plead insanity.

In July, Dix replaced his public defender because she urged him to plead guilty and take the minimum two-year jail sentence (rather than risk the maximum five-year sentence for threatening someone's life across state borders). "I mean, what kind of a lawyer tells you that doing time is unavoidable?" Dix asks in disbelief from the Atlanta City Detention Center.

Despite the fact that he signed a death threat and sent it to Turner -- and faxed it from his home fax machine -- he believes he has a case.

"To sentence me, they have to prove criminal intent. But if you read the letter I wrote to Turner, you see that I end it with: 'If you press charges, I will have my day in court,'" says Dix. "I just wanted to get the case into court so I could publicly document my side of the story. I had no criminal intent to kill Ted Turner."

As Dix anticipates his vindication -- and waits for a trial date to be set -- he passes time reading "Exploring the World of Lucid Dreaming" by Stephen Laberge, playing cards and strategizing chess moves.

Meanwhile, his mother, Carmela Silvestri -- having invested more than $35,000 of her own money in Dix's business -- tries to keep the product afloat. "We still have one major store -- H.E. Butt Grocery Co., in San Antonio, Texas. They still order 288 units of floss rings every month," she says. The grocery company doesn't know about Dix's arrest, and the family is afraid that if it finds out, it will stop ordering the product, as so many others have.

The East Coast chain Eckerds, which bought $22,000 worth of floss rings in 1997, has since discontinued sales of the product. H.E. Butt has spent just $380 on the rings this year.

"But I've gotten about 18 letters of request from people who have read about the rings and want to try them," Silvestri says. "I'm just trying to maintain things as status quo so when Sean gets out he can bring the business back to the level he left it at, and take it further, of course."

Are the rings a perfect product yet? Silvestri sees a problem that one of the dentists pointed out on the CNN segment: Tying the string around the rings is not convenient. "But Sean has patented a segment that would make the whole process a cinch; he just needs the funding to manufacture it," she explains.

As I sit with Silvestri in her cluttered East Village home, she prods me to try the dental aids that led to her son's current predicament. She's a frazzled but gentle public school teacher, and she slowly and intensely demonstrates proper use of the ring.

After a bit of difficulty getting the floss around the small plastic pieces and locking it into place, I sit back and enjoy the easiest, most thorough flossing session I have ever experienced. Silvestri lights up.

"See?" she says. "There is still hope that these things will take America by storm."

(Nicole Bode helped research this article.)

Shares