When Hirotada Ototake was born, his mother was told she couldn't see him straight away because he was "too weak." A few days later it was: "They say you can't see him for a little while longer because he has severe jaundice." She soon understood that something serious was going on, but being in Japan, where a doctor's word is gospel, she felt unable to ask what was happening. Eventually, Ototake's mother was informed that a disability -- not jaundice -- was the reason she had not been allowed to see her baby. And so it was that three weeks after his birth, Ototake met his mother for the first time, staff standing by to assist her if she fainted. It's through this anecdote that readers, like his mother, are introduced to Ototake, a Japanese man born with congenital tetra-amelia, that is, without arms or legs.

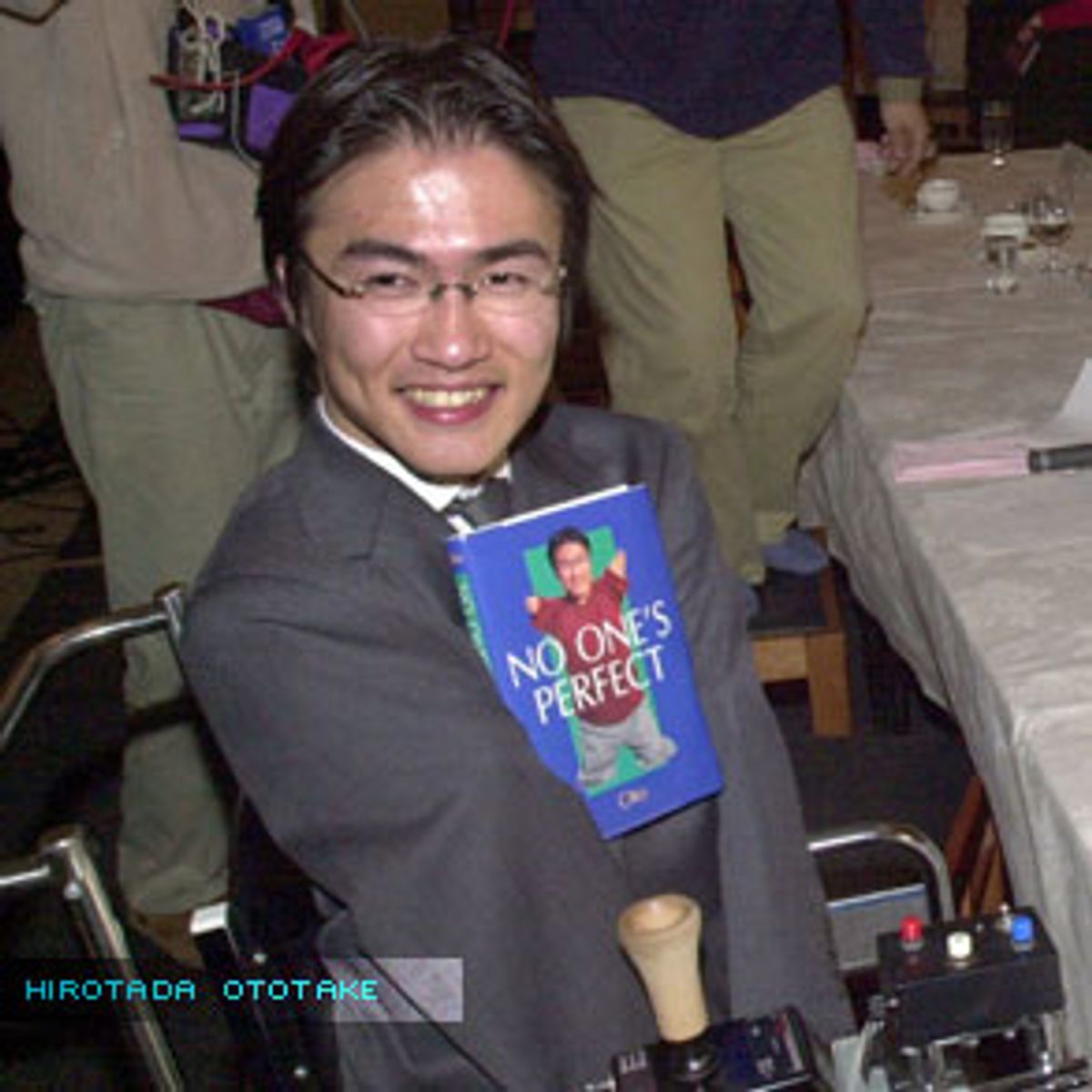

Ototake, now 24, wrote and published his autobiography, "Gotai Fumanzoku" in 1998. It became the No. 1 bestseller in Japan from December of that year through November 1999, and since its release, the book has sold about 4.5 million copies, which, according to publisher Kodansha Ltd., makes it the No. 2 bestseller in Japan since World War II. Called "No One's Perfect" in English and translated by Gerry Harcourt, the book has just been published in the United States.

"Gotai Fumanzoku" is a phrase invented by Ototake, and it literally means "not a complete, healthy body." It's a play on the Japanese version of that universal sentiment: "We don't care if it's a boy or girl, we'll be happy if it's just born healthy." In Japan they say "gotai manzoku": with all limbs and body parts satisfactorily in place.

Both the book's title and its main assertion -- that the disabled can lead fulfilling, interesting lives and be happy people -- have startled Japan. Anticipating some discomfort with the topic, and the possibility that it might be largely ignored, Kodansha had printed only 6,000 copies in the first run.

So what are the ingredients that have catapulted Ototake and his autobiography into literary history? It's that just by telling his story, Ototake shatters the Japanese belief that the disabled are to be not only pitied but never even spoken of. Despite its author's dramatic disability, "No One's Perfect" is essentially about a kid growing up, learning to make friends, coping with pressures at school and being accepted by his community. Rather than proclaiming his normalcy, Ototake conveys it by recounting life-shaping vignettes in a conversational style that makes readers feel as though they're watching a home video.

Ototake's story is full of unassuming heroes, from the teacher who encourages him to compete in the 50-meter dash on his butt in front of the whole school to the classmates who insist he not be left behind on their field trip to climb Mount Kobo -- and who end up pushing and carrying him in his chair to the top. Then there are his parents, about whom he deliberately keeps much private. Faced with a severely disabled child in a society where disabilities are generally a source of shame, they take his condition in stride, accepting his differences and adjusting their own lives so that he can live as normally as possible.

And of course the central character is Ototake himself, who manages to achieve a remarkably typical childhood: making friends, trying to be cool and participating in regular school activities. When he sets his mind to it, he achieves great things; when he slacks off, he gets bad grades. All the while, just by living his life and being himself, he cuts through other people's discomfort with his disability and teaches them to see him first and foremost as another human being.

Although Ototake admits to loving the limelight, he insists that he's not the heroic figure he's been cast as by the media and his fans. On this subject he has said: "My parents were shocked but not saddened or depressed by my disability. I've always thought that they loved me. Does it mean that they are strong? I've often been told I was strong. But I think that the whole family just did not realize how challenging the situation was. I don't think we tried to overcome it. We were simply a happy family."

It is this humility, which he exhibits even now after attaining celebrity status in Japan, that moves the reader and makes Ototake a hero, despite his protests to the contrary. He does not intellectualize his life. There's no trace of bitterness, and there's no sense that he isn't just what he claims to be -- a regular guy. Still, the degree of his book's success is surprising. Sociologists, those who work with the disabled and the general public agree that until recently, the Japanese have shown very little awareness about the disabled and the challenges they face.

As Yuko Kawanishi, a sociology professor at Temple University in Japan puts it: "Most Japanese people don't really know so much about physically handicapped people's reality. They don't see them so much because they have much less visibility. So there is a lack of understanding, an ignorance." As a result, disabled people in Japan usually avoid the spotlight. In Ototake's words, "This doesn't mean they are confined. Rather they may think it's too much trouble to go outside. Japanese people tend to stare at people with disabilities."

And, as Ototake and other disabled people are increasingly making it known, access to public facilities and transport is poor in Japan. Rather than inconvenience or embarrass others, traditionally the disabled and those related to them have accepted prejudice and poor access and adjusted their lives to compensate.

But a subtle and gradual change in attitude has created an environment receptive to -- even hungry for -- Ototake's message. As Kawanishi puts it: "Japanese people are now in a mind-set to welcome this sort of hero." Motoki Yamazaki, executive director of the Specially Challenged Persons Health and Welfare Department in Fukuoka, says that perceptions have been evolving over the past decade: "Although there have been groups representing the disabled for some time, recently there has been a growing change in attitude about the disabled -- both among themselves as well as among the public at large --- of their right to participate fully in society."

Yamazaki sees Ototake as a skilled writer who presents a very appealing -- particularly for the Japanese -- image of someone who is trying very hard. In this sense, he feels that the book speaks to, and has greatly influenced, a growing change in consciousness in the Japanese public, who have come to recognize that discrimination against the disabled is wrong. Above all, Ototake's book has given the public the first popular, well-written account that allows them for the first time to identify with a Japanese person with a disability.

But the upbeat attitude that has made Ototake's book so popular has also been the source of its most serious criticism. Ototake's experiences are just too perfect to ring true for some readers. According to his account, his family was unfazed by his disability and the classroom experiences he describes are overwhelmingly positive -- in fact, he doesn't recount a single bitter personal encounter in the whole of his academic experience.

And though his disability is severe, Ototake himself is handsome, bright and articulate. In short, he's an ideal poster boy, easy for people uncomfortable with disabilities to latch onto. He's never sharp-tongued about the injustices committed against people who don't fit into the mold in Japan. In fact, Ototake avoids dealing with the dark side of prejudice against the disabled; from reading his book you might think that the only reason Japan isn't more friendly to disabled people is because its people aren't aware of them. This strikes some observers as incredibly naive. Others have speculated that with maturity, Ototake's sunny outlook may change.

So what does Ototake's story offer readers in the U.S., where the status of the disabled is said to be 40 or 50 years ahead of that in Japan? The author, who tends to idealize the situation in the States, says: "Maybe people in the U.S. are already used to my message, and it'll be no big deal." It's true that the disabled have both a stronger history of activism in America and more laws to protect them.

But are most Americans really that comfortable with the disabled? Do we truly see them as individuals who can lead fulfilling lives and not as the objects of pity? As one American English teacher living in Japan put it, "Access has been ingrained into us in the U.S., but I don't know if most people know how handicapped people really think, unless they have direct interaction with them. They still may see them as very different from themselves and be scared of them. This guy, who has a very dramatic disability, is a happy person. I believe this is relevant even in the U.S., because most people here are also scared and uncomfortable with disabilities. There's a huge difference between agreeing that handicapped people need access, and certain rights to protect them, and understanding how a disabled person truly thinks."

Here's another thought. In this day and age of fetal testing, amniocentesis and bimonthly ultrasounds -- all of which can lead to the aborting of imperfect fetuses -- what are the chances that someone like Ototake would even make it to birth in the U.S.? This book is a reminder to the most technologically sophisticated of societies that who you are and your value as a human being are distinct from physical soundness.

Finally, for U.S. readers this book is a cross-cultural gold mine. Anyone reading "No One's Perfect" will stumble upon the most interesting facts about growing up Japanese. Ototake's classmates structured special rules for him so that he could participate in their games at recess. The coach had him play on his school's basketball team. This could only happen in a society where winning is less important than being part of the team -- a rather faded notion in America, where the drive for individual athletic success reigns supreme.

Throughout his life, Ototake struggled to be accepted at school, first being forced to prove that his physical limitations didn't indicate that he also had mental ones, and then being forced to prove to school administrators that his presence would not be too disruptive to the group, all important in his culture. At each school transition, from elementary to junior high to high school, while other kids could pick and choose their next institution, Ototake's admission into any school at all was always hanging in the balance. When accepted, he felt relief and gratitude. Even today he says that he considers himself fortunate that Waseda University accepted him, although he passed the prestigious school's rigorous entrance exams.

Ototake's ability to make his point, while skillfully adhering to the Japanese code of humility and self-effacement, has greatly contributed to the popularization of the notion of a barrier-free society in Japan. Indeed, the success of his book may prove that, given an "acceptable" catalyst, and despite all theories to the contrary, Japanese society and its prejudices really can change.

Shares