Late Sunday afternoon, Ron Felling stood with a knot of friends before the rail at Yogi's, a local sports bar, looking melancholy.

Some of the patrons who recognized him seemed perplexed; it was as if they expected to find Felling gloating at the news of Indiana University basketball coach Bob Knight's firing. A former assistant coach to Knight for 15 years, Felling is suing his former boss and the university. Felling claims Knight assaulted and fired him earlier this year after eavesdropping on a private conversation with a former colleague in which he discussed Knight's propensity to "rant and rage."

But as discussions all over Yogi's raged about Knight, Felling seemed remarkably subdued. Citing his pending case, all he would say for the record about Knight's sacking, as he gently shook his head, was "It's unfortunate. But it's over."

In one sense, Felling couldn't have been more wrong.

While Knight is also known as "The General" for his Patton-like style of coaching, the sobriquet is also apt for the Castro-esque cult of personality Knight commands in Indiana. In the Hoosier State, basketball has been the ribbon that binds the state's cities and small towns together; while Texas communities have their sacred Friday night football games, the holy rites of hoops reign supreme here. And no ground is more sacred than I.U.'s Assembly Hall, presided over for nearly three decades by one man whose rapport with his fans bears more than a passing resemblance to the relationship between another set of obsessive students (circa 1978) and a certain zealous imam.

So it was hardly surprising that last night Indiana University went from being a picturesque campus to a grotesque parody of a half-assed banana republic coup.

Early in the evening, a throng of at least 2,000 students showed up at I.U. president Myles Brand's house, where they burned him in effigy. From there, they proceeded down 7th Street and then cut over to Kirkwood Avenue -- Bloomington's main drag -- where they gathered in front of venerated local watering hole Kilroy's, alternately chanting "We want Bobby!" and "We want beer!"

"We're on Kirkwood, dude ... there's, like, business to smash up here!" one of the many shirtless, backward ballcap-wearing students marveled, as he and others beheld a line of Bloomington cops in full riot gear. "This is not going anywhere," a cop said into a walkie-talkie.

Eventually, after a few near run-ins with baton-wielding cops and irked by the non-welcoming townie response, the crowd turned around and headed for campus.

"Obviously, we're pretty mad," Kurt Squire, a 28-year-old grad student majoring in information technology, said as his large, black dog trotted along next to him. "The students weren't involved in the process." As if to underscore his point, at that moment, half a dozen students set upon the well-planted placard to Franklin Hall, rocking it violently and uprooting it, while yards away, two guys went to work on uprooting a street sign, drawing the wrath of a cop who took off after them and, in turn, found himself pursued by hundreds of students, chanting variations of "kill the pig."

The march then turned toward the cathedral of Indiana hoops, Assembly Hall. Tumbling down Dunn Street like the bull runners at Pamplona, the crowd made straight for the array of TV satellite trucks, exploding into cheers anytime a mobile camera's light shone on a swath of crowd. Various chants were screamed, ranging from "Fuck Myles Brand," "Go to hell Harvey" and "Die Harvey die" (for Kent Harvey, the freshman who last week accused Knight of grabbing him and angrily rebuking him for failing to address him as "coach" or "Mr.") to "Kill Harvey."

Though the crowd was by and large peaceful, some seemed ready to rush the boys in blue in the name of Knight. Some in the crowd tried to set fire to trees in front of Assembly Hall, spurring one person to ask, "What'd the trees do to Knight?" Others set fire to pictures of Harvey or banners bearing his name. In the end, the mob dispersed and left. Or so it seemed.

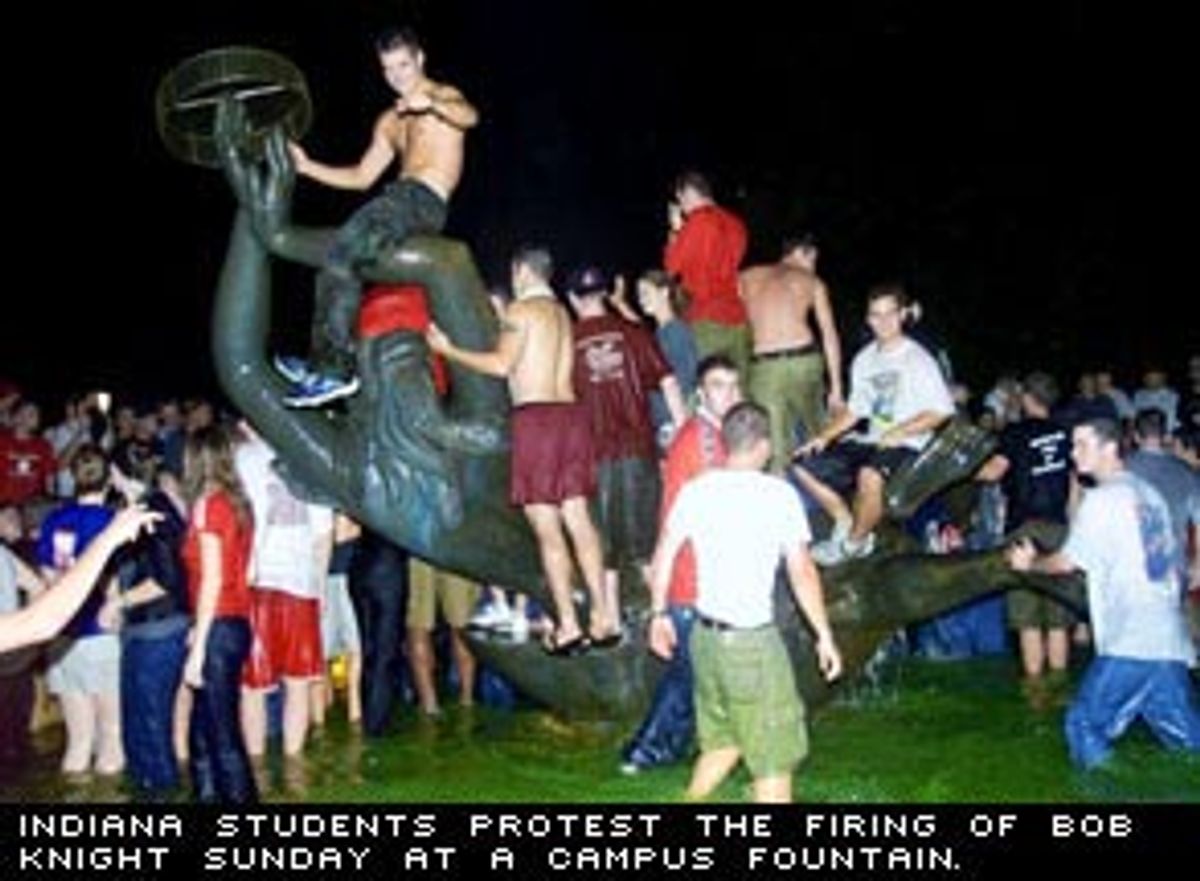

Protesters reconstituted and joined up with another pack at I.U.'s Showalter Fountain, wading in and wrenching exceptionally heavy iron dolphins from their cabled moorings. (The vandalism at the fountain offered a sharp contrast to the last time students attempted to deface the statue -- during post-game hijinks after Knight led the Hoosiers to a 1987 NCAA win.)

Meanwhile, not far from the fountain, the I.U. president's house had come to resemble that of a besieged head of state's residence under the protection of U.N. peacekeepers. Instead of blue helmets, the two dozen state troopers deployed around Brand's house wore Smokey the Bear hats. While some officers were resolute ("ain't no one gettin' in this house tonight"), others looked nervous as the roar of the unseen horde filtered through a misty grove of trees now littered with uprooted iron light posts.

Back at the fountain, it was an angry bacchanalia: Adding a touch of Mardi Gras to the protest, chants had expanded to include "Tits for Knight" and "Boobs for Bobby," requests some of the drenched co-eds were only too happy to entertain. Having given up on their attempt to remove the entire statue of Venus, a handful of young men hefted one of the iron fish up and carried it, surrounded by a protective crowd chanting everything from "Fish! Fish! Fish!" to the now-standard assortment of pro-Knight, anti-Brand/Harvey riffs, back over a mile to Assembly Hall.

One young man, who would only give his name as "John," bore the brunt of the purloined fish's weight, carrying it for at least a mile over earth, tarmac and gravel, bereft of shoes, before depositing it as an offering of sorts at Assembly Hall. Passionately but calmly, he explained his ardor. "He's been at I.U. for almost 30 years -- we've grown up being proud of Bob Knight for what he's done for this state and this university.

"He's the reason most of us come here -- he's part of a tradition," he earnestly continued. "You take that tradition away, it's like taking part of our hearts, part of our spirit, away." He added that while removing the fish from the fountain had not been easy, "Our spirit and determination for Bob Knight carried us through."

And then, Generalissimo Roberto himself emerged from Assembly Hall. Reported to have been in Canada on a fishing trip, he had apparently returned, and the crowd went wild. "I want all the police officers behind me," he said, driving the crowd into a frenzy of delight.

Then, after Knight offered a brief defense of the cops, the crowd listened attentively as he explained that he would call an assembly of students later in the week and tell them "my side" of recent events. And with that, he accomplished what squadrons of police hadn't: He got the crowd to go home, peacefully.

By any standard, Robert Montgomery Knight has had an exceptional coaching career. Though he has not won an NCAA championship since 1987, he has delivered three such titles to Indiana University over three decades. Save one other coach, no man has won more college basketball games than he. Knight also presided over the 1984 U.S. men's Olympic basketball team, which took the gold. And he has been widely praised for running an ethical program that doesn't quietly pay players or their families, has no patience for prima donnas and extols the virtues of teamwork.

On the other hand, Knight's career has been one of the most controversial in American athletics, owing largely to what even his partisans see as an anger management problem. In 1979, while serving as U.S. coach at the Pan American Games, he was convicted in absentia in the American territory of Puerto Rico for hitting a police officer. In 1985, angered by a referees call, he registered his displeasure by hurling a chair across a basketball court.

The recipient of scores of game ejections and costly fines for his tongue-lashings of referees, a university investigation earlier this year concluded that he had engaged in a pattern of inappropriate actions -- including manhandling at least one player -- and could only stay at I.U. if he accepted a $30,000 fine, a three-game suspension and adherence to a "zero tolerance" conduct policy.

The policy hadn't even been drafted yet when, last week, Harvey -- who just happens to be the stepson of local attorney and ex-radio talk-show host Mark Shaw, a vociferous Knight critic -- saw Knight and said, "Hey, what's up, Knight?" Knight then allegedly grabbed Harvey and lectured him (perhaps in colorful language, perhaps not) about the importance of addressing elders with the proper honorific.

As Brand explained at the Sunday press conference announcing Knight's firing, Knight was not being canned over the Harvey incident, but for a pattern of "uncivil, defiant and unacceptable" actions since the conclusion of the earlier investigation. It's the type of stuff that few in the public or private tolerate: refusal to acknowledge his superior, athletic director Clarence Donninger (only recently given any real authority over Knight), refusing to meet with alumni and loud badmouthing of just about everyone. Salon has also learned that recently, when I.U. counsel Dottie Frapwell went to meet with him to discuss defense strategy regarding Ron Felling's lawsuit, he "blew up at her and ran her out of his office," according to a source familiar with the situation.

To an older generation of Bloomingtonians, none of this is surprising, and they're relieved that the boom has finally been lowered on Knight. It's not that his iconoclastic, politically incorrect style irks them; even if one disagrees with his principles (and he has them), he's always been tremendously entertaining. But that he's assiduously built and cultivated a power base on appearing to be the maverick but is, in fact, a bully who operates with impunity, has been profoundly disturbing to some.

"He's a demagogue, and any demagogue needs worshippers, and he certainly has a houseful of kids here who don't know the history that older alums who live and work here do," one local merchant says. "I can say a lot of good things about the guy. But what's scary about him is how he gets people to not only believe his myth, but believe it so strongly and blindly they don't think."

He chuckles. "There was a guy I knew who was the biggest Bob Knight fan in the world. Dan Dakich (a former assistant coach) brought him down to the locker room once to meet Knight, and for no reason, Knight made this guy feel like two cents waiting for change. His faith was destroyed. He should have known better. But to a lot of people, especially the kids, Knight can do wrong."

Shares