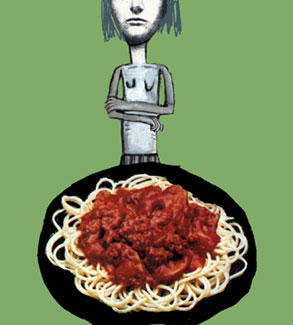

My heart began to pound, shaking my protruding collarbone and rattling my jutting wrists. Blood turned to lead in my trembling arms, anchoring them to my lap. Voluntary movement was not possible. I’m not ready for this, I thought. I faced the pile of spaghetti, alone.

A hill of stretched, pale worms wound around each other. Dark scabs of meat infested the blob of red goo that sank the mound’s middle. It looked like it could writhe at any moment. The smell conjured up a meal at “Mom’s Italian Restaurant” on Route 27 rather than the institutional cuisine I’d expected. That didn’t matter. To me, sustenance meant guilt and revulsion. I could sooner have swallowed a piece of homemade ravioli as chewed a giant beetle that crunched and then squirted.

Anorexia nervosa literally means nervous loss of appetite, but that’s not accurate. Like the bodies of other anorexics, mine yearned for food. Conventional wisdom holds that taming hunger instills a sense of control and mastery that a person lacks elsewhere in her life. The late 1970s, when I was sick, marked the beginning of what turned out to be a boom in eating disorder awareness in the general population. Girls of my generation, however, didn’t invent these illnesses. Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics depict conditions that resemble what we now call anorexia nervosa so it’s probably been around for at least several thousand years. The first formal account lies in a medical paper from 1689, in which a patient was described as “a skeleton clad only with skin.” For a long time, anorexia nervosa was thought to be a form of tuberculosis or a manifestation of some other physical disease. It wasn’t until the 1930s that researchers began to think that this type of self-starvation might stem from psychological roots.

Today, symptoms of eating disorders — inappropriate dieting, maladaptive preoccupation with shape and weight, and overvaluing the role these characteristics play in a person’s life — are extremely common, although the full syndrome of anorexia nervosa strikes rarely. Experts estimate that about one-half to 1 percent of young women suffer from the disease. Many factors probably contribute, and researchers are investigating the roles of personality traits, family structure, social patterns, biology and cultural influences. Several recent studies, including one that involved 2,000 twins published earlier this year, have suggested that predisposition to anorexia is inherited. This result implies that certain forms of genes put people at risk for the disorder, thereby focusing attention on genetic as well as environmental factors. In many ways, I was a typical anorexic — female, adolescent, conscientious with a perfectionistic streak, and seemingly happy and successful, yet haunted by feelings of defectiveness and loneliness. In contrast to the textbook cases, however, I was acutely aware of what I was doing, and why.

I had gone to a lot of trouble to land myself in the hospital. At 15, I had embarked on a diet and had shed 50 pounds in six months. My body had started out slightly padded, clad in baggy painter’s pants to conceal my thighs. As I shrank, I wore tighter pants to flaunt my success, until those too began to hang on my diminishing frame. By summer, my pelvic bones looked as if they could cut my bathing suit. I snuck downward glances as I walked briskly to the edge of the pool, admiring how they rose sharply to define the valley that used to be my belly. Now a vast chasm of air separated my thighs when I stood with my feet together. The contours of my ribs resembled a row of black piano keys, and bald cords of sinew had replaced my neck. When I unzipped my jeans, they dropped to the floor.

To accomplish this dwindling feat, I memorized the USDA’s book of nutrition and dug out my mother’s scale for weighing food. I slid the shiny knobs back and forth to measure exactly 100 grams of cherries. After I’d lost 20 pounds, my mother wanted me to put it away and stop tallying calories.

“You’ve reached your goal,” she said, “You’re thin enough.”

The times I failed to shove it all the way into the corner on the top shelf, she knew I’d been sneaking it out.

“You’re trying to cause trouble,” she’d accuse, yanking open the cutlery drawer.

So I left the scale in the cabinet and honed my ability to weigh with my eyes. I dished noodles into a measuring cup in my mind and multiplied the calories in one grape by the number in the cluster on my plate. My chest clenched when I had to estimate the calories in a bowl of soup or a heap of casserole. It relaxed when I encountered a single-serving Rice Krispies box or a pre-packaged frozen bag of broccoli in cheese sauce. I could just read the nutritional information label.

If I added about one and a half times as much water as the package of instant oatmeal called for, I didn’t dilute the flavor too much, but felt as if I was eating a heartier breakfast. For variety, I might try half an English muffin (dry) with a slice of cantaloupe. That gave me a good 100-calorie start on the day. Lunch was more of the same, though sometimes I’d substitute the fruit. No blueberries, though — too many calories per feeling of fullness. For dinner I might eat a bowl of iceberg lettuce (dressed in a few drops of water), a drumstick of skinned chicken and maybe a small baked potato.

Under this regimen, I biked, swam, ran and played tennis every day that summer, except when I was vacationing with my parents in Switzerland. There I woke early to stuff the croissants meant for breakfast into my knapsack before my mother and father appeared in the dining room. I ate my lunch high in the Alps, amid snow-capped mountains and green lawns dotted with wildflowers, perched on the other side of the rock so Mom and Dad wouldn’t see how small I pared the cheese, and so they wouldn’t witness the surgical procedure with which I removed the soft part of my rolls. I screened my activities with hunched shoulders, my body taut with deception. I had never liked egg yolks so at least I could eat only the whites (which carry most of the protein, but few of the calories) in the open.

I scrutinized every decision about what I would eat and do. Did it contribute to my program of maximizing the ratio of expended to consumed calories? I refused to go on trips that would confine me to a vehicle for hours at a time. I could burn only so many calories jiggling my legs. I avoided situations where dinner was served after 7 p.m. Too close to bedtime — not enough hours to walk off my so-called meal. For a treat, I might go to a movie. But once inside the theater, I couldn’t concentrate on the screen. I was too busy thinking about what not to eat the next day. Nothing was really funny, anyway.

Even as I starved myself, I took pains to avoid permanent damage. I always drank enough so my electrolytes wouldn’t get out of whack and provoke a heart attack. And although I knew I could stick my finger down my throat, I succumbed to the urge only once. I could imagine bingeing and throwing up forever, without being noticed, and that was not what I was after.

I wanted to feel better, but not the kind of better that gaining weight would bring. I wanted to feel better from the rottenness that had been metastasizing in me before I’d quit eating, the sense that I was invisible except if I was misbehaving or inadequate. In one of the few instances that my father had taken time off from his laboratory experiments to participate in my life, I’d humiliated him. As he returned from Back to School Night, I looked up from my homework with a smile. He frowned and said grimly, “Your English teacher embarrassed me in front of the other parents. She said you whisper to your friends throughout class.” My mother was home more, and would stop practicing cello for important events — such as the moments I bounced in the door on a report card of A’s. She’d inspect and return it, saying, “In math, you can get everything right. You should be earning an A-plus.”

I had already tried spewing suicidal poetry. “Can’t you write something that does not reek of depression?” my ninth-grade creative writing teacher had admonished when I shared some of it with her.

Erasing myself was both an offer to my parents and a plea for help. I had invested a great deal of thought and energy into my appeal. It had to pan out.

My vague plan had partially worked. My friends urged me to try the chocolate chip cookies I baked for them. My parents weren’t canceling their trips to the Metropolitan Museum of Art or giving away their “Carmen” tickets to play rummy with me, but my increasingly prominent bones pierced the polymer mesh that enveloped my chemist father and the clumps of hair in the garbage prickled my mother’s thorny shell. He coaxed me to eat more while she ranted.

“You’re doing this on purpose,” she’d scream. “You want to keep getting skinnier and skinnier.”

She was right, sort of, but no one seemed to see past the surface. I didn’t want to glaze my skeleton with a reassuring layer of tissue, or pink up my cheeks until I felt solid.

At the beginning, I had mapped out my caloric intake and energy output, and often struggled to stick to my plan. Coffee fudge ice cream sang to me from waffle cone platforms, beckoning my tongue to plunge into its smooth sweetness. I’m not sure exactly when I ceded control to my illness, but eventually I was no longer directing my diet; it was directing me. “Don’t eat that,” I’d hear as I lifted the smaller half of an English muffin to my mouth. “Don’t nourish yourself,” a voice bellowed, stilling the edge of my spoon a mere millimeter into a cantaloupe’s flesh.

My diet had seeped its way through my mind. I saw billboards that said “Sandy Beach” and read “Sandwich;” “Next Gas,” “Ex-Lax.” I’d lie in bed, sleepless and shivering, while chocolate honey-dipped Dunkin’ Donuts tumbled frantically through my head and pizza slices topped with sizzling cheese careened around, hovering directly in front of my mind’s eye to taunt me.

The diet was insatiable. “Two more laps today,” it demanded. “Pedal faster.” Simultaneously, it slashed my meals. Cutting melon slices thinner and abandoning increasing portions of my allotted food filled me with a soothing calm.

I shriveled inside my diet, which swelled with every pound that I lost, every bite I didn’t take. Eventually I looked out from inside my withering body to see bars on all sides.

One evening my father appeared at the doorway to the living room to announce dinnertime. I looked up from the book I was reading and suddenly went limp inside. “I can’t eat,” I told him. “I need professional help.” Surely someone would know how to nurture the slim part of me that wanted to thrive.

Several days later, the first professional I visited prescribed Thorazine, Stelazine and three bowls of soup every day.

“You’re nervous,” that psychiatrist said.

“I’m not nervous; I’m anorexic,” I replied.

“If you know that you’ll die if you don’t eat, and you still won’t eat, you’re nervous,” he reasoned.

He had a point. But I knew I’d keep losing weight on three bowls of soup a day. Does he know anything about calories? I wondered. And I don’t know exactly what those drugs are, but if the dentist said I was too scrawny for laughing gas, why isn’t this guy worried about oversedating me?

By the time my parents and I got home from the appointment and trip to the all-night pharmacy, the little confidence I’d had in his approach had vanished.

“I’ll just fall asleep,” I explained. “That’s not what I need.”

My mother made a fist around the pill bottles and shook them at me. “You don’t really want to get better,” she said. “You’re just wasting everyone’s time.”

“I do. This won’t work,” I replied evenly, gulping tears. “How about a hospital?”

Several phone calls and a 90-minute trip to an eating disorders specialist secured me a spot at Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania, site of one of the most progressive anorexia programs in the world. Dr. Collins had treated dozens of anorexics. She even noticed that I was wearing a sweatshirt on a sweltering day, and asked if I had trouble concentrating and how much hair I was losing. Plus she could explain why my calves hurt. “Your body’s breaking down protein for fuel.”

I was experiencing the relatively minor symptoms of anorexia. Self-starvation can lead to serious and sometimes irreversible physical problems, including irregular heart rhythms that can trigger heart attacks, kidney damage, infertility and weakening of the bones. Studies have shown that up to 10 percent of patients with anorexia admitted to university research hospitals die of complications. I didn’t really want to wind up in that category.

Once I knew I’d be going to the hospital, I could sleep more easily. I had done my part and now someone else would help me recover. I stopped eating almost entirely during the two weeks between acceptance into the hospital’s behavior modification program and the day I was admitted. That way I didn’t have to fight with myself about every morsel I put in my mouth. By the time I faced my first meal, I figured, someone would have asked me why I was doing this, and then listened as I began to explain. That person might say, “You will feel better eventually, and in the meantime, you’ve got to sustain your body.”

I had finally arrived. All afternoon, I had hung around my room, thinking that maybe Dr. Collins would drop by to remind me that this treatment had helped many other girls. I had sat on my bed, resolving to tell the truth about my thoughts and habits to the therapist who’d undoubtedly show up and assure me I’d heal with a lot of hard work.

No one came.

And now, here was this plate of spaghetti. If I didn’t get it into my stomach, I wouldn’t gain my half pound for that day, and I’d spend the following one with the yellow curtains pulled around my bed. That was part of the hospital deal — and I was ready to hold up my end. Yet no one had even talked to me, much less cured me.

Oh my God, I’m on my own, I realized.

I tried to quell the terror stemming from the guilt mounting inside me. Somehow, immediately, I had to transform myself into a person who deserved to eat.

My eyes locked on the spaghetti, and then filled with tears. They don’t have any magic answers. I got myself into this and I’m going to have to get myself out of it.

My gaze crept from the plate on the wheeled tray table to my thighs on the bed. They were already swelling, as my stringy legs dangled.

Inside my mind, I grasped the frayed, straining rope that connected me to a future self — someone who could again enjoy the thwack of the ball when playing table tennis, who belted out “Anything Goes” to her big brother’s piano accompaniment, who could thoroughly inhabit the novel she was reading. Someone who could even lick the batter off a wooden spoon, and whose sense of self-worth didn’t correlate with descending numbers on a scale.

I raised my eyes to confront the now-blurry spaghetti.

Then I lifted my hand and forced my thumb and fingers around the fork. Sinking the prongs into the towering strands, I slowly started twirling.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

Sites that can help

While no one can save a person with anorexia or other eating disorders, professionals can and do help. For information about eating disorders and treatment options:

Eating Disorders Awareness and Prevention Inc.

Anorexia Nervosa and Related Eating Disorders Inc.

National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders