The results from last week's debate between Hillary Clinton and Rick Lazio are now in, and they point to one overwhelming conclusion: The experts completely missed the boat. I watched the debate with my 9-year-old son, Alex, who at one point turned to me and asked -- a little gleefully -- "Do they ever actually fight?"

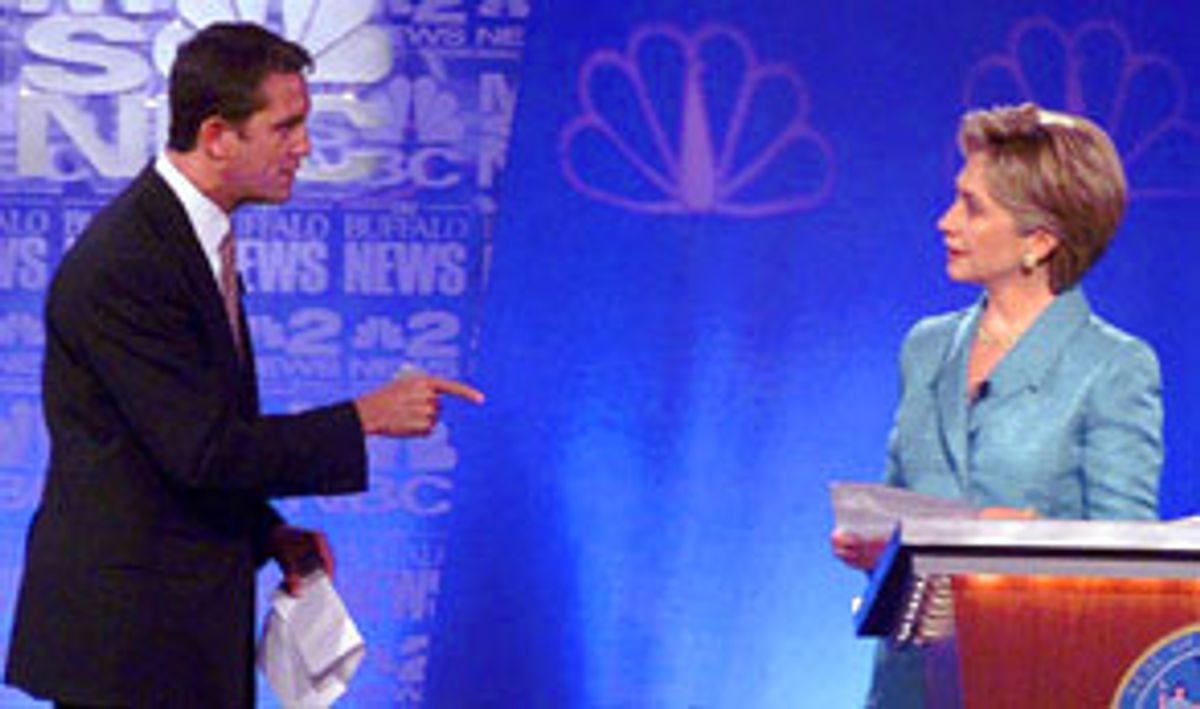

The possibility had crossed his mind, not during the climactic moment when Lazio crossed the stage to demand that Clinton sign a pledge to abstain from the use of soft money, but during one of his lesser encroachments on her airspace. Lazio's behavior felt not only unremittingly hostile but artifically so: He seemed like a fundamentally soft figure who had been instructed to act tough, and had inadvertently spun the dial all the way to rabid. Clinton, on the other hand, struck me as measured, deliberate, professional. I scored her as winning almost every round. (I gave the nod to Lazio when Clinton said that communities should be allowed to decide for themselves whether they want casino gambling, and Lazio said flatly that gambling was the wrong way to go about economic development.)

And then I listened to the post-fight commentary, and felt, as Clinto said of Lazio, that I had been "orbiting another planet." Immediately after the debate, on MSNBC's "Hardball," Peggy Noonan, a notorious Hillary-hater, described the first lady's manner as "robotic." Even Clinton chronicler Gail Sheehy, presumably slotted as pro-Clinton, scored the fight as a draw. All agreed that Lazio had shown his mettle. In the next day's paper, experts impaneled by the New York Daily News gave Lazio the nod 57-50; the editorial page concluded that Lazio "had exuded a more New York sense." The New York Times editorial page, no friend to either candidate, called Lazio the "smoother, more aggressive performer." David Broder declared that Lazio had proved himself a force to be reckoned with. What had looked to me like comic swagger and cartoonish bluster had registered as confidence and backbone with Broder. Times columnist Gail Collins did describe Lazio's performance as "crazed," but voices like hers were markedly in the minority.

And then the vox populi was weighed and measured. Instant polls were mixed -- one for Clinton, two for Lazio. But opinion was remarkably unanimous among undecided voters. All six of the fence-sitters whom the Times had been following in recent months felt that Clinton had carried the day. In USA Today, the figure was eight for eight. Of the 10 undecided voters polled by the Buffalo News, most had moved into the Clinton column. And a Times/CBS poll conducted between one and six days after the debate provided the decisive evidence: Not only was Clinton voted the winner 47-34, but a majority of voters believed that Lazio had been too aggressive, while scarcely any felt that way about Clinton. In fact, the debate helped Clinton widen her lead in the poll from five to nine points.

The same language kept recurring in interviews: One respondent told the Times, "He came off as a much more immature person, and she came off very collected."

The extremely wide range of judgments should remind us that the means of expression available to us -- gesture, tone, word choice, facial expression -- are so open-ended and indeterminate that three people scrutinizing the same set of behaviors can offer three different interpretations. But in this case the range has a pattern. What can explain the gap between expert and ordinary opinion? One hypothesis is that the public didn't get it, and the experts did; that is, that Clinton really was robotic, and Lazio really did exude a more New York sense. But this would be odd, since the experts are essentially trying to anticipate public opinion rather than form a personal impression. A likelier explanation is that the undecided voters were reacting to their own intuitive judgments, while the experts were reacting to their own expectations. The experts, in effect, weren't receiving their own intuitive judgments.

This is, of course, a general problem with expertise. You can't fully experience any new performance of "Macbeth," or "La Traviata," because you're conditioned by the expectations created by so many prior peformances. You hear what you already "know." In this case, Noonan "knew" that Clinton was robotic -- and of course wanted her to be robotic -- while the communications mavens impaneled by the Daily News, who may have had no preference of their own, "knew" that Lazio's likeability was bulletproof, and so must have come across as "feisty" rather than nasty. In contrast, the undecided voters, who were hoping to make a decision based on what they saw, had good reason to clear their minds of predisposition. They actually experienced the performance before them. (I, of course, may have been influenced by my dim view of Lazio, which I have expressed in print; but I don't hold Clinton in terribly high regard either.)

But there is something Clinton-specific at work here. The great media blunder of the last few years was the widespread projection onto public opinion of the media's own scorn for President Clinton. The media thought that it was anticipating public opinion, but in fact the public resisted the media's own view.

Something similar may be at work with Hillary Clinton. I can't count the number of times that I have been confidently told over the past year and a half that Clinton was not only going to lose the Senate race, but that she was going to get shellacked.

Until very recently, Clinton has been widely seen as a loser -- a personal view which, as with the president, took the form of a prediction about public opinion. And scorn for Hillary, a whole subject in itself, runs even deeper than scorn for her husband, since she's charmless, bland and self-righteous -- and sometimes mechanical -- while he's a seducer and a rogue. Indeed, a shrink recently explained to me her theory that people hate Hillary as compensation for their inability to hate Bill, much though they feel he deserves their contempt.

Scorn keeps you from seeing straight -- or hearing accurately. Clinton is never going to be popular, but she has always had a better shot at winning the race than she has been credited with. She is, after all, a pro, which is more or less what she demonstrated the other night. It's fairly clear that the debate will come to be seen, in retrospect, as a modest step forward for Clinton, and a serious step backwards for Lazio. The Times poll found that her favorability ratings had grown slightly since June, while his unfavorables had soared. It may be cosmically unfair that the Clintons just keep on winning, but the truth is that they're better than the competition.

Shares