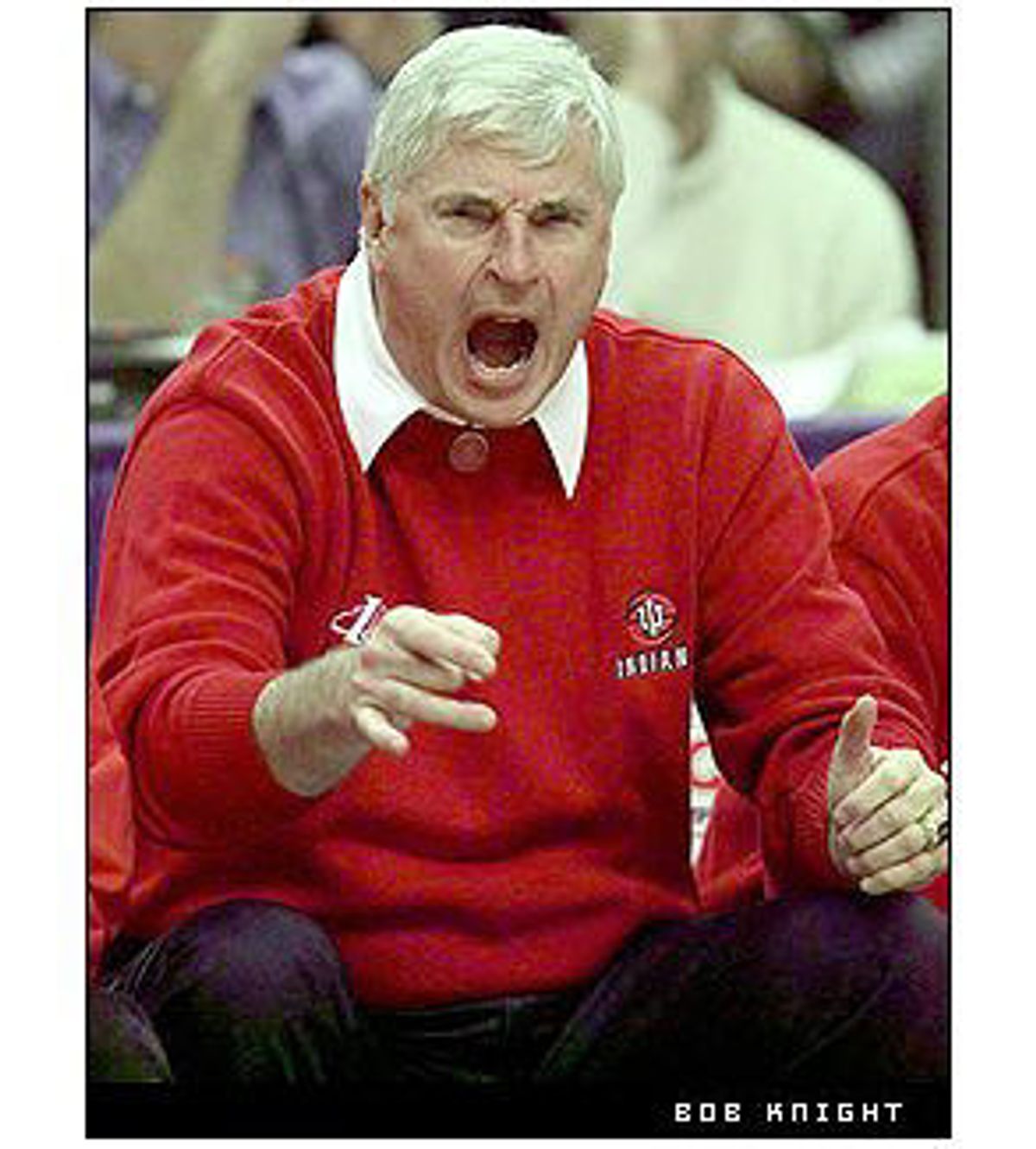

No, I've never hit a Puerto Rican policeman before practice at the Pan-American games; stuffed a fan from an opposing team in a garbage can; told Connie Chung, "I think that if rape is inevitable, relax and enjoy it"; told women, "There's only two things you people are good for: having babies and frying bacon"; pretended to bullwhip my star player; waved used toilet paper in my players' faces to provide them with a metaphor for their poor play; tossed a chair across the court during a game; kicked my son -- a player on the team -- in the leg during another game; head-butted a player during yet another game; or choked another player during practice. But neither have I won three NCAA championships, twice been named coach of the year, coached the United States to an Olympic gold medal, won more than 700 college basketball games or had a higher graduation rate among my players than nearly any other Division I basketball coach.

Me? I remember being simultaneously a graduate student in the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop and a patient in the university's equally renowned Speech Clinic, and being overwhelmed by the paradox that as an apprentice writer I was learning to manipulate words, but that as a stutterer I was at the mercy of them. How had my life come to this, I wondered, shuttling back and forth between two four-story brick buildings, two houses of language?

I wanted gorgeous language to be my revenge upon the Babel of my speech; I wanted somewhere within the world of words to succeed hysterically. Twenty years later, I love language as much as any element in the universe, but I now have trouble living anywhere other than in words. If I'm not writing it down, experience doesn't really register. Language has gone from prison to refuge back to prison. (Bob Knight once said, "All of us learn to write by the second grade; then most of us go on to other things.")

Is it clear how Knight and I are alike? In short, what animates us inevitably ails us. Not only for Knight and me, of course, but for everybody. What has been largely absent from all the coverage and commentary following Knight's dismissal from Indiana University earlier this month for violating its "zero-tolerance" policy is recognition that, for all of us, the force for good can convert so frighteningly easily into a force for ill. Our deepest strength is indivisible from our most embarrassing weakness, and what makes us great will inexorably get us in terrible trouble. Everyone's ambition is underwritten by a tragic flaw.

"A great painting comes together," Picasso said, "just barely." That fine edge gets harder and harder to maintain. I yield to no one in my admiration of Renata Adler's first novel, "Speedboat": It is, I think, one of the most original and formally exciting American novels published in the past 25 years. And I hesitate to heap any more dispraise upon her recent, much-maligned memoir, "Gone," which I must admit I found utterly addictive. But surely the difference between "Speedboat" and "Gone" has to do with the fact that in the earlier book, the panic tone is beautifully modulated, under complete control, even occasionally mocked, whereas in the later book it has been given, somewhat alarmingly, absolutely free reign. Success breeds self-indulgence. What was effectively bittersweet turns toxic.

We all contrive different, wonderfully idiosyncratic and revealing ways to remain blind to our own blindnesses. My 7-year-old daughter is (my wife and I think) unnervingly observant about the subtlest human gesture; she's also wildly oversensitive to the slightest slight. In the current British television series "Cracker," Eddie Fitzgerald is a brilliant forensic psychologist who can solve the riddle of every dark human heart except, of course, his own. (He gambles nonstop, drinks nonstop, smokes nonstop, is fat and is estranged from his wife.) Richard Nixon had to undo himself, because -- as hard as he worked to get there -- he didn't believe he belonged there. President Clinton's fatal charm is his charming fatality: His magnetism is his doom; they're the same trait. Someone recently said to me about Clinton, "By all accounts he could have been, should have been, one of the great presidents of the 20th century, so it's such a shame that ..." No. No. No. There's no "if only" in human nature; it's all one brutal feedback loop.

And when our difficult heroes self-destruct, watch us retreat and reassure ourselves that it's safer here close to shore, where we live. We want the good in them, the gift in them, not the nastiness, or so we pretend. Publicly, we tsk-tsk, chastising their transgressions. Secretly, we thrill to their violations, their violence -- psychic or physical -- because through them we vicariously renew our acquaintance with our own shadow side. By detaching, though, before free fall, we preserve our distance from death, stave off, at any cost, serious knowledge about the exact mixture in ourselves of the angel and the animal.

In college, when I read Greek tragedies and commentaries on them, I would think, rather blithely, "Well, that tragic flaw thing is nicely symmetrical: Whatever makes Oedipus heroic is also ..." What did I know then? Nothing. I didn't feel in my bones as I do now that what powers our drive ensures our downfall, that our birth date is our death sentence. You're fated to kill your dad and marry your mom, so they send you away. You live with your new mom and dad, find out about the curse, run off and kill your real dad, marry your real mom. It was a setup. You had to test it. Even though you knew it would cost you your eyes, you had to do it. You had to push ahead. You had to prove who you are.

Shares