I hit the wall last night. Locked up. Fingers dead on the keyboard. Lactic acid filled my typing muscles. Just couldn't keep up the pace. Forget about medaling: Hell, I could feel those flag-waving hacks from the Telegraph coming up on my shoulder. Luckily, I had gotten two tablets of cold medicine past customs (I told them it was a "food supplement" -- Ha!) I popped them and bang! Minute amounts of pseudoephedrine to the rescue! If the prose that follows has the grace and style of an Andreea Raducan beam routine, and I know it will because I'm pumped, don't thank me -- thank Theraflu.

So now the world is shocked, shocked that an unprecedented number of drug cheats have been caught at the Games -- including, most dramatically, a Romanian hammer thrower who was escorted off the field Wednesday as she tried to compete. The only thing that surprises me about the whole drug-cheat flap is that it took so long for steroid-filled heads to start rolling. I read a lot of stories about drug testing going into the Games, all of them more or less contradictory, and the one thing that seemed clear was that the whole testing situation was as full of holes as C.J. Hunter's alibi. Obviously the tests were going to be more stringent than ever before, which was a good thing, but just as obviously they weren't universal or foolproof -- not everyone was going to be caught. Moreover, as the flap over the U.S. Track and Field Association's lame coverup of the names of athletes who tested positive demonstrates, the administration of the system lacked both transparency and consistency.

This was a recipe for disaster. Until Olympic officials decide they're simply going to institute Draconian measures like continuous blanket testing, or whatever they need to do to make sure no athlete is using banned substances, this problem isn't going to go away. In the meantime, poor Andreea Raducan -- whose crime appears to have been taking cold medicine given her by a moronic team doctor -- saw her appeal to restore her stripped gold denied by the Court of Arbitration in Sport, which upheld the International Olympic Committee's original ruling. I understand the reasoning that no exceptions can be made, but under the dubious circumstances that surround the whole drug-testing business, to make an example of her seems unjust and mean-spirited.

The U.S. is taking its deserved lumps here over the USTF's refusal, on procedural and fairness grounds, to release the names of the athletes who tested positive. "[I]f the United States of America, with all its hand-on-its-heart-holier-than-thouness on so many other subjects ... is not going to lead the fight against drugs in sport, then who is?" railed Sydney Morning Herald columnist Peter FitzSimons, and it was hard to argue with him. On the other hand, it's hard to take the moral outrage expressed by much of the Aussie press (there must be special keyboards here that allow journos to input words and phrases like "shame" and "brave" and "honour" and "legend" and "our hope" and "Australia's pride" with one finger) seriously after observing the cheesy way they jumped on the C.J. Hunter scandal. Story after nudge-nudge-wink-wink story insinuated that Jones herself had been fatally tainted by association with the nandolene-laden shotputter. Just why being married to a drug cheat -- if that is in fact what he is, which certainly appears likely -- taints Jones was never made clear, but it didn't need to be. Most of it was tabloid sensationalism, and some of it was just wishful thinking: One scribe, dutifully trying to find a gushy Cathy Freeman angle in every subject, floated the idea that with Marion distracted and demoralized, Freeman might be able to beat her.

(I have to admit I am beginning to find the endless feel-good orgy here over Freeman's victory in the 400 meters, and the attendant deep, self-congratulatory cultural analysis about the great racial strides it represents, a little strange. A black woman from our country won a middle-distance race! Oh my God! Let's declare a month of national celebration!)

So on the Games go. I suppose now I should wonder which athletes have the blood with the muscle-bound cells swaggering around in it, but I don't. I may be naive, but I doubt that many athletes are taking banned substances -- even with the absurdly flawed procedures in place, the risks of being caught are too great. Of course, I have no way of knowing that, but I choose to believe it, mostly out of self-interest: If you suspect everyone of being a drug cheat, it pretty much takes the fun out of being here. Moreover, the events where drug abuse seems to be most rampant are the power sports -- weightlifting, shot put, hammer throw -- and much as I enjoyed watching the hammer throw (the indentation the ball makes in the sod is especially gratifying) if it is found to be suspect, my world will not crumble. The same goes for nationalities: The most suspicious athletes, statistically, are Romanian and Bulgarian musclemen, and they make up only a very modest part of my Olympic experience.

Actually, I did take in some seriously muscular dudes today (Thursday), although I suspect not many of them were of the steroid-taking variety. Feeling in the need of a little palate cleanser after what seemed like two dozen straight track meets, I went down to Darling Harbor and checked out some freestyle wrestling.

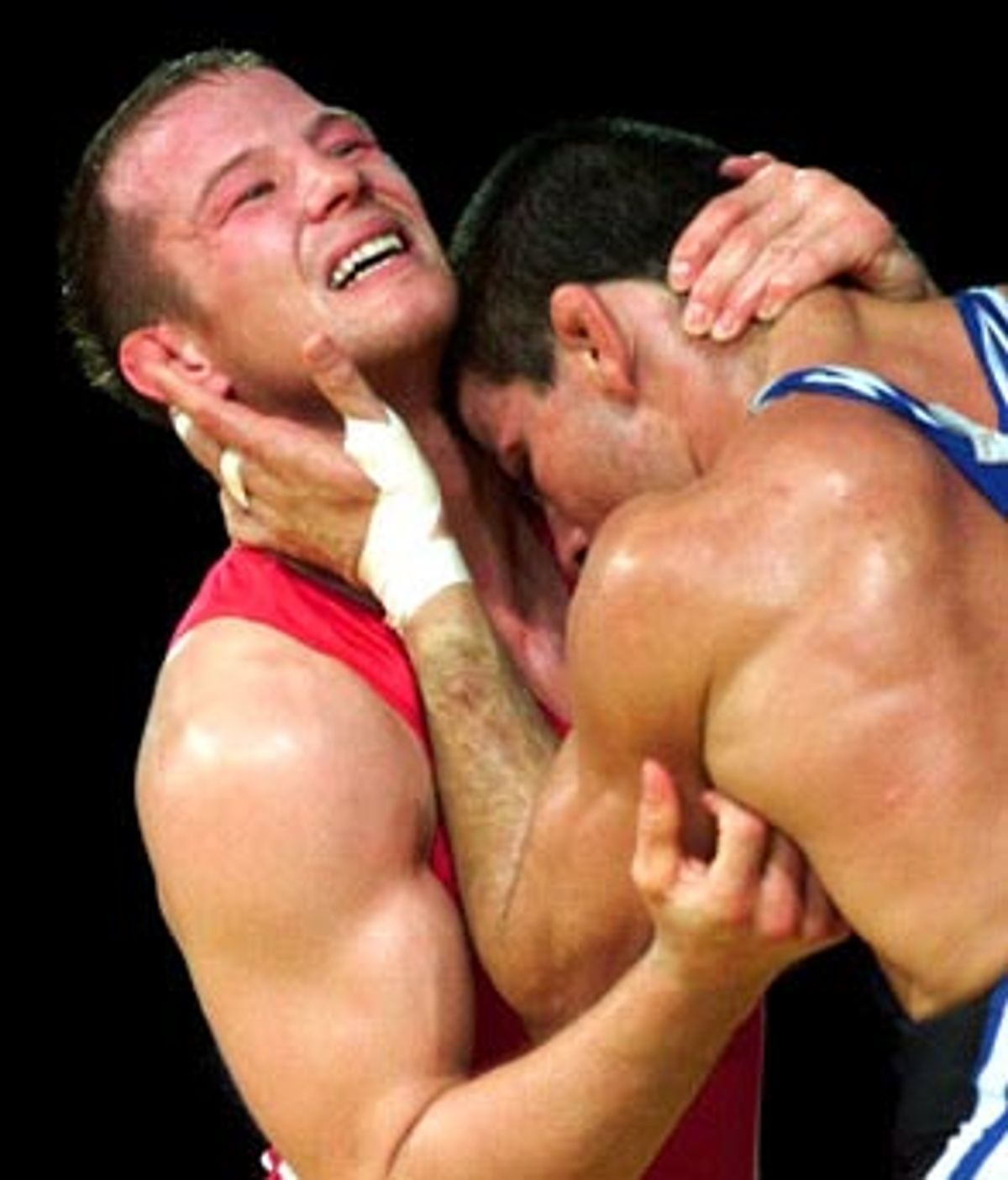

As I walked under the bleachers to go to my seat, I could hear one of the most animated crowds I've heard at any venue -- lots of yelling, screamed expert advice, applause. When I emerged, a weird spectacle appeared. It was a nice, clean gladiatorial arena -- three ferocious, primal physical duels going on simultaneously on a nice new clean blue stage. For the first few minutes, I hardly knew what to look at. It was a three-ring blur of unbelievably intense encounters, raw animal power, snake-like speed and grim tenacity combined with an arcane, sweaty knowledge of how to control a writhing, resistant mirror image of your own body. I had wrestled a few times in junior high and high school, and my brother was on the high school wrestling team, but I'd forgotten almost everything I ever knew. Luckily there was a guy sitting behind me who was delivering an expert running commentary. I try to find these guys wherever I go.

Basically, the idea in freestyle wrestling is to gain control of your opponent or, better still, take him down. You get points for either of those achievements. You can win either on points or by pinning your opponent.

What freestyle wrestling really is is war. Compared to it, all other sports feel somehow secondary, derivative. You can't get any more primal, more man-against-man, than this: Two guys who are probably the cardiovascular kings of the entire Olympics (wrestling is like sprinting as hard as you can with every muscle in your body) grappling, grabbing, slapping, squeezing, working with violent precision against a slab of obscenely plastic, angry clay, until one moldable angry slab gains mastery and the other is utterly, completely defeated, annihilated, dragged by the heels around the gates of Troy. When you are pinned in wrestling, you have lost.

Watching, an old, painful memory I had forgotten suddenly came back: When I was still in junior high, we went to watch my brother wrestle, my big strong older brother who could kick my ass, and he got pinned. It was a terrible feeling, watching him futilely try to "bridge" (use his head and neck to keep his shoulders off the mat). His opponent inexorably drove him down, my brother thrashing and stretching while I looked on in stunned disbelief, until the referee's hand smacked the mat and it was over. It was like watching death.

Oddly, the memory didn't sicken me. In fact, it reminded me of the beauty of the sport, its precision, its elegance. They call boxing "the sweet science," and not without reason, but wrestling really deserves the name. You can be as strong as a bull and as fast as a snake, but if you don't know exactly what you're doing, you will lose. It is applied physics where the classroom is the human body and the theorems are written in muscle and blood.

But it is vicious. The last match of the day, in the 63-kilogram (138 lb.) division, featured a top-rated American named Cary Kolat against a wrestler from Uzbekistan named Ramil Islamov. Kolat was clearly the superior wrestler, but Islamov went into a defensive shell and was fortunate in scoring the first point. But then Islamov was penalized for passivity and the match heated up. Kolat, circling, feinting toward the upper body and then grabbing his opponent's legs with lightning speed, had Islamov in desperate trouble. The Uzbeki escaped -- and then fell in what appeared to be agony to the mat, clutching his leg. Time was called and an official sprayed his leg with some kind of anesthetic.

A nicely dressed, middle-aged American woman sitting behind me wasn't having any of it. Obviously, feigning injury was a good way to suck air. "Why don't you give him some oxygen while you're down there?" she yelled. "You guys are cruel," commented the expert.

The match resumed, the American continued his relentless attack. "That's it, Cary -- work the leg! Keep attacking it!" yelled the wrestling mom. (Note to presidential candidates: Wrestling moms may be too intense to be used as icons of suburban maternity.) And again, at the first break the Uzbeki fell to the mat holding his leg, his face contorted. Out came the official again. "Boo! Boo!" yelled the wrestling mom, joined by several other women and now the expert, too. "Fight or quit!" they yelled. "Fight or quit!" Thumbs down in the arena!

Finally, Kolat pinned the guy. As they stood on either side of the referee, Islamov really did look like he was hurting. But wrestling is a tough sport.

As I walked out, groups of men, some of them swarthy and slightly Asiatic looking -- there's a long tradition of wrestling in the geographic arc that runs from Iran through Kazakhstan to Uzbekistan -- were looking intensely at chalkboards that listed the results. An American fan was raging about some earlier decision that had gone against Kolat and apparently had taken him out of medal contention. "I'm just so angry I can hardly speak!" he spat, walking off. Other guys were gathered together, handicapping upcoming matches. It reminded me of the deep knowledge and passion that so many fans bring to these lesser-attended sports.

This evening, Thursday, was the another big night of track and field. Marion Jones was going for her second gold, in the 200 meters.

She got it. At least, I think she did -- it was kind of hard to see. A few days ago I was kvetching about sitting up with the gods, but the last two nights I've been right down on field level, at the opposite end of the stadium from the starting lines for the sprints but not facing the finish line, either. Believe me, you don't want to be there -- except when watching a race that goes all the way around the track, when you have a superbly dramatic view of the runners going by. I have a very powerful pair of binoculars, and all I could see of the 200 meters was: 1) a few half-obscured bodies in the blocks; 2) a few half-obscured bodies running around the curve; 3) many clear bodies coming down the straight; and 4) a finish that, because of the angle, was very difficult to call.

Well, it was difficult to call except for Marion Jones, who did a few errands, fixed her makeup and chatted with friends while waiting for the rest of the field to catch up with her. Jones appears to be from some other planet. It isn't fair. It's like an NFL wide receiver being covered by a high school linebacker. A large spike-filled pit in the middle of her lane might have prevented her from winning, but nothing else. She was in control from the moment she hit the curve and came out of it smoking, and then down the straight she got medieval on their asses. She clocked 21.84, an eternal .43 ahead of Pauline Davis-Thompson of Great Britain. (In one of what is becoming a delightful procession of unexpected nations crashing the garden party, Sri Lankan flier Susanthika Jayasinghe took the bronze.)

Jones' victories are splendid to behold because you're watching greatness, just massive once-in-a-lifetime talent. And greatness doesn't get boring, even when the races aren't close. But the many upsets we've had have added a terrific spice to the mix -- like the unexpected 800-meter victory by Nils Schumann of Germany on Wednesday night. And Thursday, yet another dark horse came flying through, this time in the men's 200. While everyone was looking at Ato Bolden or John Capel or Obadele Thompson or Christian Malcolm, there was this Greek guy named Konstantinos Kenteris. He ran a pretty good semi time, 20.20, the same as Bolden and a tick faster than Thompson, but Capel put up 20.10. Besides, white guys don't win 200s -- not since the great Valery Borzov in 1972, if you leave out the boycotted 1980 Moscow games when Italy's Pietro Mennea won.

But this time a white guy did win the 200. Capel got a terrible start and wasn't a factor, and Kenteris came flying down the straight to just beat Great Britain's Darren Campbell, clocking a 20.09 -- the slowest Olympic 200 in 20 years. Yes, Michael Johnson or Maurice Greene would probably have eaten Kenteris' lunch, but they weren't here. Throw in the silver in the women's 100 won by Ekaterini Thanou and these are Greece's finest sprinting results ever in an Olympics. Mercury is rising!

The other standout event of the night was a classic long jump shootout between Australia's Jai Taurima and Cuba's Ivan Pedroso, one of the greatest long jumpers of all time. Waving his arms and working off the deafening roars of the crowd, the inspired, pumped-up Taurima turned in the jumps of his life, springing up from the pit and throwing his hands over his head in disbelief at how far he'd gone. With only one jump left for the Cuban, Taurima led Pedroso, 8.49 meters to 8.41 meters.

I couldn't see the long jump at all, but I watched Pedroso's face on the big screen as he prepared for his final jump. He is an elegant, cool-faced, goateed man, and he studied the track with impassive calm. He began his run, with that loose-jointed, bouncing gait that long jumpers start with before they kick up to almost top speed, hit the board and soared, legs churning, before landing with perfect form far down the pit. When he got up, the crowd was silenced. A few moments later his distance was shown: 8.55.

Pedroso walked back along the track from the pit. Now I could see him in the binoculars. As he walked slowly back, he was the fiercest, most intense-looking competitor I've ever seen. He looked like Wyatt Earp and Billy the Kid and Doc Holliday all rolled into one, utterly fearless, too strong to be arrogant, knowing he had done what he had to, looking neither to left or right as he came down the track. In the background, thousands of faces appeared clear and sharp in the glass, all screaming, for now it was Taurima's last jump. Up, up above the deadpan, walking Cuban I could see the open-mouthed faces stretching, up into the upper stands, like a set in a Wagner play. The sound cascaded down. On Pedroso walked, one impassive man against a brilliantly colored background of thousands. He reached for a towel and began to flap it at himself. He did not look at Taurima, who had exhorted the crowd until the sound was like a continuous roar. Taurima hurtled down the track. Pedroso did not watch.

Taurima's last jump was short. Pedroso knew it from the sound of the crowd and began to walk down toward the pit. Another athlete briefly touched hands with him, but Pedroso didn't change his gait or his expression. It wasn't until he saw the announcement and ran over to the stands and was pulled backward, pulled on his back right into a chanting, screaming mass of Cubans, that I saw him smile. And then the joy broke over him and he roared and laughed, and the last I could see of him he was still laughing.

Shares