When George W. Bush promises to restore "honor and dignity" to the White House, everyone knows that, although he's talking about the Monica Lewinsky sex scandal, he's not just telling us he won't have sex with cherubic interns in the Oval Office or that he's a fiercely devoted, monogamous family man. Bush is making a point about "character."

"Character" is the mantra of Bush's campaign against Vice President Al Gore and President Clinton. He mentioned "character" nine times in his acceptance speech at the Republican Convention. In other speeches he's made as many as 20 references to character. He's even pledged doubling funding for "character education," whatever that is.

The only problem with all his talk about character is that it really doesn't tell us very much about, well, Bush's character. We have some idea what Bush means when he uses the word; he talks a lot about compassion, conservatism, credibility and his Christian awakening. In his address to the party faithful in Philadelphia he associated character with virtues such as abstinence, family love, courage, self-denial, responsibility, faith, idealism, charity, vision and equality. He let us know that the Founding Fathers were men of character, and that he believes men of character read the Bible. It's hard to find fault with his agenda of virtues.

It's also difficult to leap from Bush's recitation of moral abstractions to any obvious association with his actions as governor.

Bush's character campaign is as much about the immoral character of his opponent as about his own rectitude. No one begrudges Bush pointing out Gore's chameleon-like mutability, his claim of inventing the Internet, his hypocritical advocacy of campaign finance reform, his propensity to resort to Clinton-esque defenses ("no controlling legal authority") or his populist pretensions.

But our reservations about Gore do little to advance our understanding of Bush. How do we assess him?

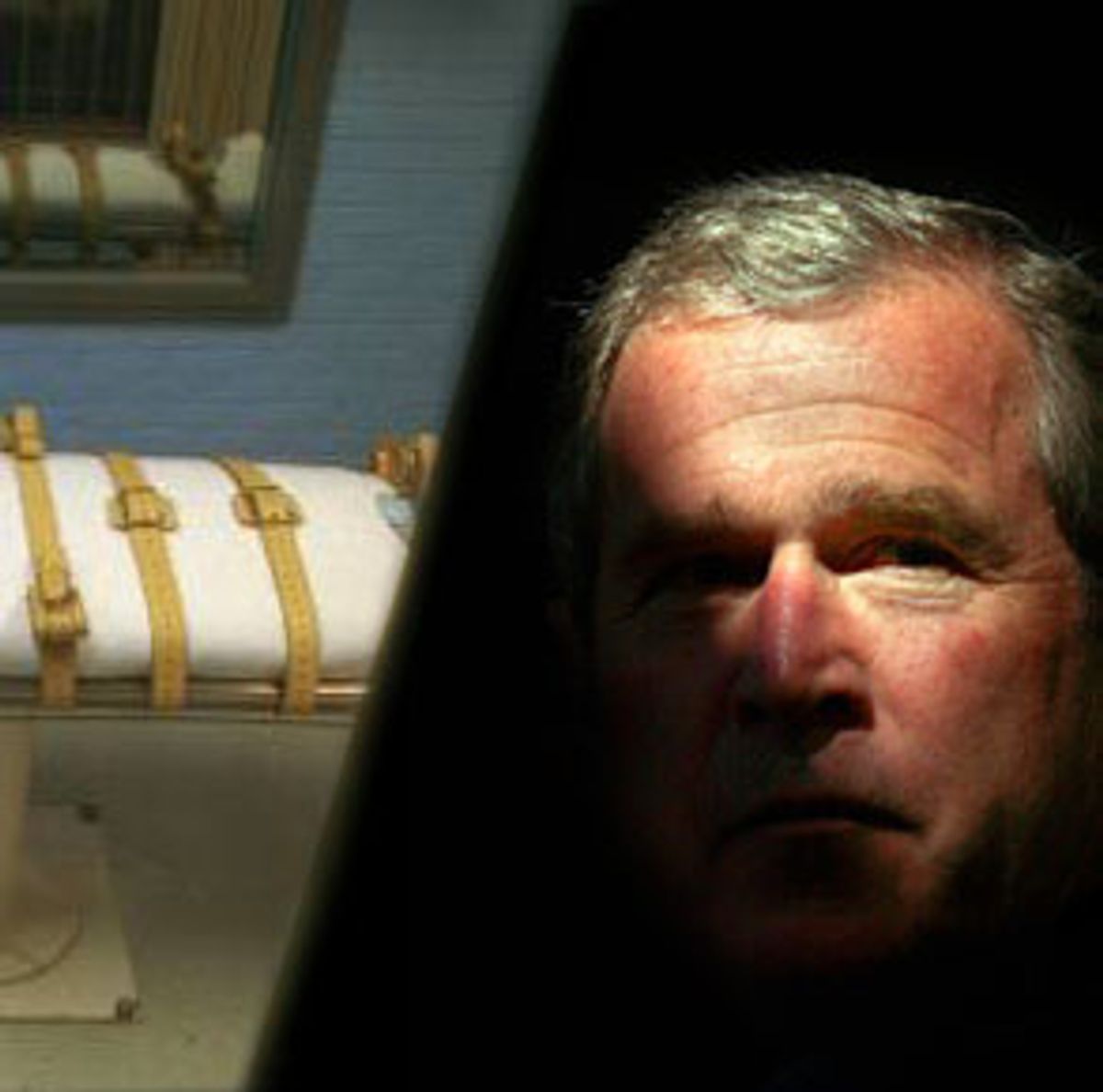

It would be fair to question the courageousness of his evading service in Vietnam, or the forthrightness of his "non-denial" denial of alleged drug use as a youth. But by far the best-documented evidence of Bush's character can be found by examining how he has handled irrevocable decisions about life and death: his decisions to approve the executions by lethal injection of 145 men and women during the past five and a half years.

One needn't be Hamlet, driven insane by a sense of duty to avenge a heinous murder, to appreciate what an extraordinary burden deciding the fate of more than 140 individuals would impose on a human being. We know that jurors, who must confront real-life murderers in the flesh, are surprisingly reluctant to impose death sentences, are often traumatized by the ordeal and may agonize for days before making a decision. Yet the typical juror is only asked to take responsibility for the taking of a single human life. Imagine the responsibility of 145.

But if many jurors have qualms about taking another life, Bush has shown no such compunction. True, one could argue, and Bush does, that juries, appeals courts and his own Board of Pardons and Paroles have already examined the evidence and come to a conclusion about guilt in the cases he reviews. But there is an equally cogent argument that this makes the governor's clemency decisions even more onerous: Given the numerous demonstrable errors in capital convictions, how can one be sure that somewhere along the line something didn't go terribly wrong?

The question here is not Bush's support for the death penalty and his often-expressed belief that "capital punishment is a deterrent" that saves lives. It is whether or not Bush has respect both for human life and for the most basic prerequisites of justice. The question is one of his qualities of leadership and whether he has behaved responsibly when the consequences of his official actions were irredeemable.

Bush insists that he regards his role in the execution process as "an awesome responsibility." He says the governor must provide a "fail-safe," what he calls "one last review to make sure there is no doubt the individual is guilty and that he or she has had the due process guaranteed under our Constitution and laws."

In practice, Bush has taken every opportunity to exempt himself from that responsibility. "I believe decisions about the death penalty are primarily the responsibility of the judicial branch of government," he says in his autobiography, "A Charge to Keep." "The executive branch role is much more limited." Bush doesn't like to second-guess juries. He also doesn't like to second-guess police, prosecutors, judges or anyone else in the criminal justice system. He wants credit for being an unflinching death penalty supporter. What he apparently doesn't want is any direct responsibility.

Indeed, what is most astonishing about Bush's record on the death penalty is not just that he has signed off on such a staggering number of executions, but the doggedness with which he has tried to take himself out of the decision-making loop. Bush effectively argues that he has "no controlling legal authority" over these deaths.

The classic formulation of this argument surfaced in connection with the 1998 execution of Karla Faye Tucker, the brutal pickax murderer who later became a born-again Christian and won the support of longtime death penalty champions Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson. "Despite the call being sounded around the country and world, I could not convert Karla Faye Tucker's sentence from death to life in prison," Bush said. He made a similar statement in June shortly before the highly controversial execution of Gary Graham, who many people believe was innocent. "Most governors can literally stop an execution, I think," Bush told reporters. "But in Texas, that's not the case."

This is Bush's big lie and the key to his "deniability" in the execution process. It relies on the kind of legal hair-splitting that would do Clinton proud: an oft-cited Texas law allows the governor to commute a death sentence only when the Board of Pardons and Paroles recommends it. Absent a BPP recommendation, the governor is only allowed to grant a condemned inmate a 30-day reprieve. Since the board failed to recommend commutation in the cases of Tucker, Graham or 143 others, Bush insists his hands were tied.

No one who has seriously examined the Texas clemency process doubts for an instant that Bush could have stopped the Tucker execution or the Graham execution, or any other execution had he seen fit to do so. What Bush never mentions is that the governor also has authority to order the BPP to hold hearings or to conduct a serious investigation of a case where he may have doubts about guilt or due process -- or for any other reason. Bush has never done that. Even at the 11th hour, Bush could use his 30-day reprieve authority to let the board know he disagrees with their recommendation, or to say, "I'm sorry, but a person's life is at stake here; let's take another look at some of these questions."

Would Bush deign to disagree with the current board, all of whose members he hand-picked, there is no question that the BPP would turn on its heels. Bush's inaction is not a matter of law, as he claims, but a matter of choice.

The governor's near-absolute insistence on disengaging from the clemency process was brought home in the Graham case when he and his lawyers argued that he could not even grant a 30-day reprieve because his predecessor, Gov. Ann Richards, had already granted Graham one. There is no case law whatsoever to support that view. Had Bush granted Graham a reprieve it is almost inconceivable it would have been challenged. Bush could have established a precedent by standing up and saying, "The governor must be accountable" in such a situation. But Bush wanted the least possible authority for the office of governor and sought to establish that precedent with a cowardly interpretation of the law.

But the ultimate obscenity of Bush's calculated decision to hide behind the skirts of the BPP is that everyone knows the board is a fraud, a Potemkin village designed to create the illusion that there is genuine clemency review in Texas. Not only does the board conduct no investigations and hold no hearings, its members don't even meet to discuss clemency applications. "It is incredible testimony to me," U.S. District Judge Sam Sparks stated in a 1998 case concerning the board's procedures, "that no person has ever seen an application for clemency important enough to hold a hearing on or to talk with each other about."

Bush says he relies on the BPP's recommendations because "I know that I cannot possibly know all the information necessary to make good decisions." That might be a credible explanation if the board was actually providing Bush good, hard explanations for executing all these people. But as Sparks observed, it doesn't: "There is nothing, absolutely nothing that the Board of Pardons and Paroles does where any member of the public, including the governor, can find out why they did this. I find that appalling."

By relying on the board, Bush dons the mask of Justice and blinds himself to the reality of injustice in Texas. Yet he demonstrates an uncanny ability to stay on message -- or should we say "in character" -- blithely asserting that "I review every death penalty case thoroughly" and that "there is no doubt in my mind that each person who has been executed in our state was guilty of the crime committed." (Bush has intervened only once on a matter of innocence, in June 1999, when he was given clear and convincing evidence that serial murderer Henry Lee Lucas could not have committed a murder the state was about to execute him for. Bush commuted the sentence to life.) Bush is adamant that there have been no violations of due process in any of the 145 executions he has approved. "They've had full access to the courts. They've had full access to a fair trial." In short, Bush is absolutely certain: There is "no doubt."

Unfortunately, this conclusion is belied by overwhelming evidence to the contrary. The actual record in Texas is littered with injustices, with cases of men and women routinely denied due process, as well as cases of innocent people who may have been executed. For Bush to claim certainty suggests either he is hopelessly uninformed or not telling the truth. If he has not thoroughly informed himself of the issues in these life and death matters, it demonstrates the most extreme nonfeasance of office. If, on the other hand, he has done his homework, it is simply not credible for him to claim certainty.

The June execution of Graham did more to undermine Bush's credibility on his certainty claim than any capital case under his watch because it raised serious questions of both innocence and due process. It wasn't that people didn't think Graham was capable of murder. After all, he had shot one defenseless man in the neck. It was rather that fair-minded people looking at the entire record in the murder for which he was condemned couldn't make up their minds about Graham's guilt.

The evidence was ambiguous. Graham was condemned to death on the basis of testimony by a single eyewitness, Bernadine Skillern, who acknowledged that she only saw the assailant for two seconds at a distance of 30 to 40 feet. There was also evidence that Skillern was coached by police, who showed her a photo array of possible suspects, before being asked to review a real-life lineup. The only suspect in both lineups was Graham. Another witness who said he also saw the shooter did not pick Graham out of the lineup. But this witness and a second exculpatory witness were never interviewed by Graham's lawyer and neither testified at Graham's trial. There were so many questions about Graham's guilt and his incompetent representation that even the somnambulant Board of Pardons and Paroles produced five votes recommending that the death sentence be commuted to life in prison.

Did Bush execute an innocent man? We'll probably never know for sure. In his autobiography the governor writes, "The worst nightmare of a death penalty supporter and of everyone who believes in our criminal justice system is to execute an innocent man." But Bush isn't losing any sleep over Graham's execution. "I am confident that justice is being done," he said shortly before Graham was given a lethal injection.

Gary Graham was not, however, the only person executed under Bush who raised troubling questions about innocence. In 1997 David Spence was sent to his death for the grisly stabbing deaths of three teenagers, protesting his innocence until the end. Doubts were raised about Spence's guilt because the extremely brutal murders, which would have necessarily involved extensive contact with the victims, produced no physical evidence linking him to the crime. Hairs found on the mutilated remains did not match Spence. And there was testimony that Spence was framed by police. The state's chief witness against Spence, as well as two jailhouse informants, later recanted their testimony and charged that police had pressured them to lie. Bush has never publicly commented on the case.

In repeatedly assuring the public that no innocent person could possibly have been executed under his watch, Bush never mentions that seven innocent men have been found on Texas' death row in the past 12 years, including one during Bush's first term in office. (A recent Scripps-Howard Poll found that 57 percent of Texans surveyed believe Texas has executed someone who was innocent of the crime. A recent Gallup Poll shows 46 percent of Americans believe an innocent person has been executed in Texas since Bush took office.) More importantly, he brushes over the fact that he himself worked hard to pass legislation that clearly increases the likelihood that innocent people will be executed by reducing the time between conviction and execution from nine years to seven or less.

One needn't be a cynic or hold a Yale B.A. to appreciate that, if Bush's law had been in effect over the past decade, the seven men released from death row would have almost certainly been executed. Bush can talk all he wants about the need for victims' families to have "closure," but there is no escaping the fact that speeding up the execution process increases the likelihood that innocent people will be executed -- that there will be new victims.

One can, of course, grant Bush the benefit of the doubt and say, "Well, he looked at the evidence in the Spence case and the Graham case, and it seemed clear to him that they were guilty even if others were not convinced." The problem with doing that in Texas is that, unlike a typical governor of one of the 38 death penalty states who may be asked to review an occasional capital case, Bush eats death sentences for breakfast. The sheer number of executions works against his claim that he "seriously" reviews any of them. Then again, as Clinton might say, it probably depends on what you mean by "seriously." Judge Al Gonzales, who was Bush's legal counsel for the governor's first 59 executions, says Bush would typically spend about a half hour on each of the cases.

Someone once suggested that explaining due process to George W. Bush is like explaining a sundial to a bat. Last year, the governor signed off on the execution of Canadian Joseph Stanley Faulder, who was convicted of murdering a wealthy oil heiress at a trial in which the prosecutor was literally hired and paid for by the victim's family while the state's principal witness was paid more than $10,000 to testify. Does Bush really think a victim's family should be doing that? Bush approved the execution of Andrew Cantu, although Cantu had neither state nor federal habeas review of his case. Does Bush know why habeas corpus is enshrined in the Constitution? And he signed off on the death of James Beathard despite the fact that his co-defendant, Gene Hathorn Jr., recanted his testimony and admitted that he, not Beathard, had been solely responsible for the murder of three members of Hathorn's family.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals refused to grant Beathard a new trial because state law requires that new evidence be presented within 30 days after a judgment is entered. Hathorn's recantation arrived 11 months too late. How did Bush satisfy himself that Hathorn was lying? Does he really think a bureaucratic 30-day time limit should trump a human life? Does he really expect us to believe that after "thoroughly" reviewing these cases he had "no doubt" that all three men were provided due process?

These cases are not anomalies in a smoothly functioning justice system. They are, in fact, frighteningly commonplace. In June, the Chicago Tribune reported that among the 131 men and women who had been executed under Bush up until that time, 40 were condemned in trials where the defense attorneys presented no mitigating evidence or only one witness during the sentencing phase of the trial. Another 29 went to their deaths based in part on testimony by a notorious psychiatrist -- Dr. James Grigson, aka "Dr. Death" -- whom the American Psychiatric Association found unethical and untrustworthy.

And 23 were executed on the basis of testimony provided by jailhouse informants, considered to be among the least credible witnesses. Earlier this month, the Dallas Morning News reported that among the 461 Texas capital cases it examined, nearly a fourth of the condemned were represented by attorneys who had been disciplined for professional misconduct. Certainly one might make a case that some of these people were actually treated fairly despite the ostensible miscarriages of justice. But would you really want to try to make the case for all of them? Bush does.

Bush must know at some level that the Texas criminal justice system is a disgrace. He can tell NBC's Tim Russert, "I'm for public defenders," but he knows that only three of the state's 254 counties have them, that he vetoed a bill that would have expanded the program and that during his first five years in office, the state received more than $150 million in federal criminal justice funds -- and didn't spend a nickel of it on defender services.

In January, Bush's Illinois campaign manager, Gov. George Ryan, announced a moratorium on executions in his state because of its "shameful record of convicting innocent people." And what constitutes a "shameful record"? For Ryan, a strong supporter of capital punishment, it was 13 wrongful death sentences.

Bush, meanwhile, remains certain nothing could possibly go wrong and has rejected any pause in the execution machinery of Texas. "I've thought about it," he said in June. "We don't need a moratorium ... I believe the system is fair and just." End of conversation.

Bush vests the Texas criminal justice system with the kind of infallibility creationists reserve for the Bible. Part of what it suggests is that Bush, like many of the voters he is undoubtedly trying to appeal to, is willing to assume that anyone caught up in the criminal justice system is guilty. It further suggests a certain contempt for the very "law of the land" he tells us he was sworn to uphold virtually every time he signs off on another life. And it suggests he is willing to gamble with something more important than whether a tax cut or a prescription drug plan or privatization of Social Security will actually be good for America. He is willing to gamble with people's lives.

Shares