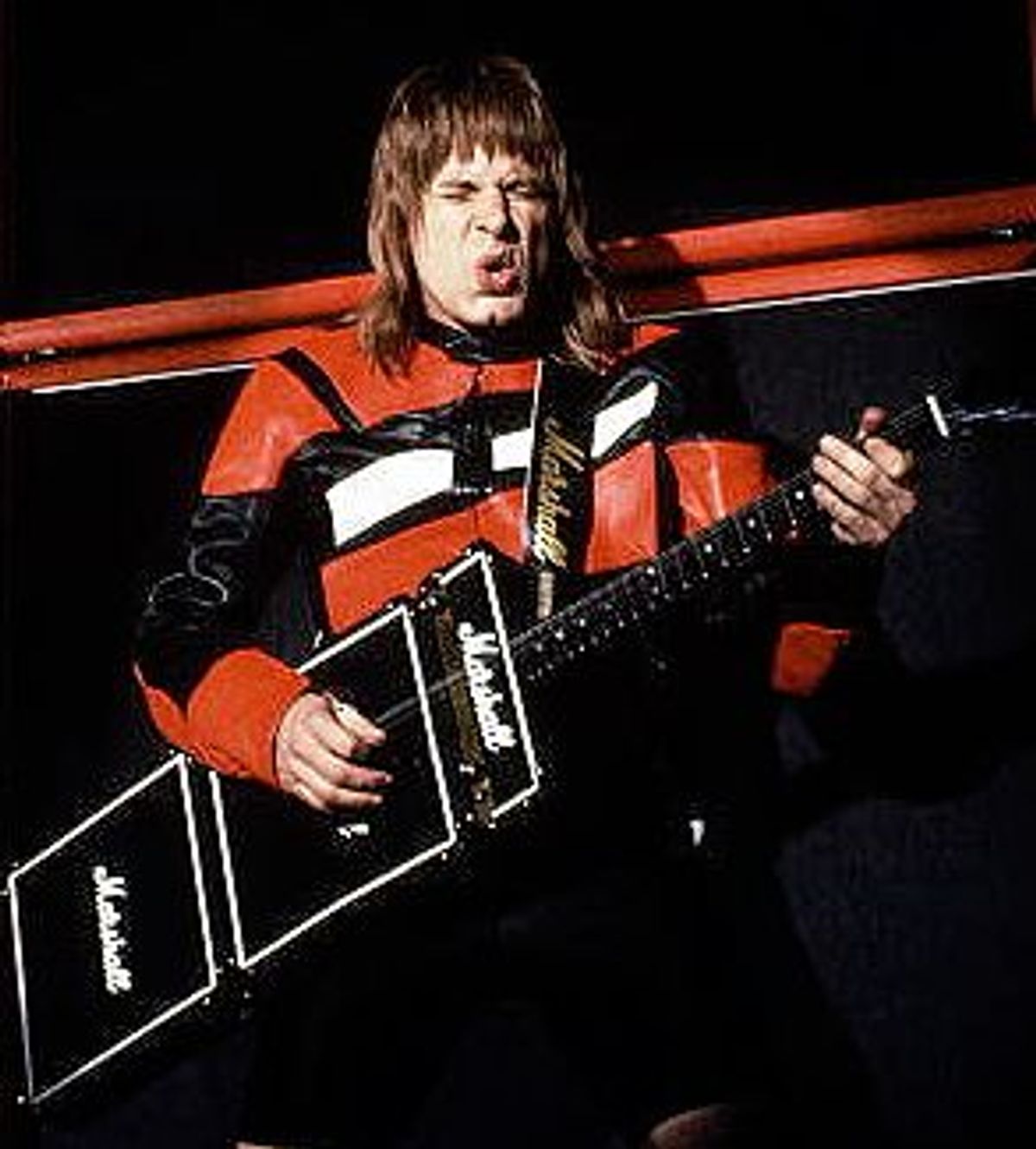

Christopher Guest is not the man you think he is. Look at his career. He worked as a scribe during National Lampoon's heyday. He had an extended and hilarious stint on "Saturday Night Live." He has made successful directorial forays into the world of the mockumentary ("Waiting for Guffman," "Best in Show"). And most infamously, he created a powerful alter ego in Spinal Tap's mullet-haired, dim-brained lead guitarist, Nigel Tufnel.

Guest, who's married to actress Jamie Lee Curtis, has written comedy for Lily Tomlin (for which he shared a 1976 Emmy) and music for the National Lampoon albums in the '70s and "This Is Spinal Tap." From these varied endeavors one would logically assume Guest to be a wacky, goofy, fun-loving fellow prone to loud guffaws and even louder ties. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The man who shakes my hand firmly in the sparsely furnished offices of Castle Rock Entertainment is silver-haired and quietly intelligent. He moves with a dignity that suits his title as Fifth Baron Haden-Guest of Saling (a role Guest inherited after the recent death of his father). He is wearing a gray cable-knit sweater and khakis, and his soft lilting voice is nearly inaudible. He does not guffaw. He does not instruct me in the ways of Olympic synchronized swimming or regale me with the benefits of an amp that goes to 11.

Instead he smiles gently and speaks of both the disparities and the intangible connections between "All in the Family" and "The Beverly Hillbillies," the structural necessities of improv and the abstract essence of comedy.

What drew you into wanting to do comedy as a kid? Comedy is such a wonderfully abstract thing, I imagine it's hard to even pinpoint your motivations.

I'm glad you figured it out. I've only done 400 interviews and no one has said that. I do think it's very hard to talk about. First of all, there's a million different kinds of comedy. And there's a lot of different sensibilities within comedy. You have comedians who don't think other comedians are funny. You just have to find your own place in what you do and what makes you laugh.

As a kid of 5 or 6 years old, I knew that there was something about what I did that was funny. I mean, you'd have to get into a serious sort of analysis to say how or why, and then it does become very abstract -- as does trying to interpret what makes people laugh.

Rob Reiner has this incredible story that really sums up this whole world. Someone came up to him while he was doing "All in the Family" and they said, "Mr. Reiner, I just wanted you to know how much the show means to me. You tackle issues that nobody else does; the whole family sits around and watches it and discusses it after -- your performance is wonderful."

And Rob says, "Oh, thank you."

And the person says, "Yeah, that and 'The Beverly Hillbillies' are really, for us, just ..."

So you have a person who likes both of those shows, which is fine. You can't be a sort of comic dictator. People like what they like. But when Rob told me that story I laughed and I thought, Why am I laughing? I'm laughing because I would think one show is more sophisticated, but you can't dictate what people are going to like.

People have said versions of that to me, surprised me by saying, "I like your stuff and X's," and I think, I don't understand. How? I think as a young comedian especially, you tend to think, Well if you like what I do, then you certainly can't like that. But then you have to get past that. I hope. You really can only worry about yourself. These are the kind of movies I make. If people like them, great. If they don't, then what am I supposed to do?

It's definitely difficult to verbalize. Humor is intangible. With the people who make me laugh, like Peter Sellers, it's something about his body language, the way he speaks, the way he looks.

Peter Sellers was my idol when I was a kid. He was the first person I looked at and thought, If I can do something like this, I'll be happy. If I can distill what he specifically did for me, it was: This is not sketch comedy. This is a deep, deep, profoundly deep character he creates. A seamless world, which was very different than other things I was seeing, which were very superficial, not thought out and ultimately uninteresting characters. If I can describe what he does for me, that's the best I can do. Because as you said, beyond that, why is that funny? I don't quite know.

I think it's also a shared sensibility. Perhaps, because of the visceral response people have to comedy, it ultimately creates an intimacy. You feel close with certain comedians if they tap into that place, if they share a certain outlook with you.

You're probably right. I've been asked about this for a long time and I find it hard to talk about because I end up going around in circles. Someone recently asked me, "Why is 'Best in Show' funny?" I said, "That's a strange question. First of all, is it funny? Is it funny to you? Is it funny to me?" Because that's a very different thing. And without getting into this thesis of comedy again, basically the question should be, "Is this movie funny to you?" But then there's still no real answer, so we end up chasing our tails.

It seems like that intimacy I was talking about is there between you and the other actors you work with in your films. You use an ensemble cast that has many of the same players. What draws you to them? What makes you decide "I want to work with this person"?

As you said earlier, these are people who, when you meet them, you immediately know are on your wavelength or whatever you want to call it. Not to say that it's all based on intuition. But if you are in the world of comedy, you can tell immediately if they are sharing a sensibility. And then they're basically in the club. For what I do, it's a small club. I'm not saying it can't expand. It's just that there's not 20,000 people walking around who share that sensibility. It's very specific. You meet them and you immediately recognize something in them. You know instantaneously. Eugene Levy makes me laugh. Why? Here we are again: I don't know.

You've done two mockumentaries. It seems like that is a framework that works for the type of improvisation your actors do.

I think it's very important to say that we start with more than a loose idea. It's many, many months of preparation. It's building a story with a beginning, a middle and an end, describing the characters, describing the characters' history. It's setting up a format that grids down every scene, as far as function, as far as plot and how each scene is moving the story along. And then you hang improvisation on this skeletal structure.

Without that framework, it's nothing. You can't just show up and start talking. I equate it with playing jazz. You have to know what key you're playing in, you have to know the music, you have to know where you're going to end up. After that it's up to finding players with good chops. And these actors have the chops.

Shares