"Dead Man Walking" is a new opera about a nun who defies authority and braves intense stigma in order to offer death row convicts friendship and salvation. Commissioned and premiered by the San Francisco Opera, the work rides roughshod over established conventions. It hasn't met an operatic precept it doesn't want to send to the electric chair.

The first rule of grand opera is that the plot should concern a woman of loose morals; this opera gives us a nun. Grand opera normally culminates in the tragic and untimely death of the heroine; "Dead Man Walking" serves up a dead man. Perhaps most important, the way to the heroine's inevitable and cathartic sacrifice should be strewn with lavish, colorful sets, exotic dance interludes and outrageous and expensive costumes. "Dead Man Walking" gives us gray prison interiors, grim fluorescent lights and dowdy, anonymous street clothes. Taken in the context of the operatic tradition, "Dead Man Walking" is either a misguided abuse of the genre or a radical reworking of operatic stagecraft.

The atmosphere at the War Memorial Opera House was charged at Saturday night's premiere, with a few dozen sign-waving death penalty opponents outside and a star-studded audience inside. Luminaries on hand for the show included Sister Helen Prejean (pronounced "pray-zhawn"), on whose memoir the opera is supposedly based, and Tim Robbins, on whose movie the opera is actually based. Also in attendance were actress Susan Sarandon, who portrayed Prejean in the movie; singing nun emeritus Julie Andrews, whose presence might have given lead mezzo-soprano Susan Graham an extra dose of the jitters; and Robin Williams, who, if he has not yet appeared on the screen in a nun's habit, is bound to do so sooner or later.

"Dead Man Walking's" journey into operatic no man's land is made all the more audacious by the fact that none of the principal creators had prior experience in the art. Thirty-nine-year-old composer Jake Heggie is known, by the few who know him, for his songs. Librettist Terence McNally earns his living on Broadway writing plays and musicals. And director Joe Mantello has acted in and directed plays and movies. With the unorthodox "Dead Man Walking," the trio made their operatic debuts. For the audience, this was akin to boarding an airplane piloted by three novices who decided, for their maiden voyage, to fly the plane backward and upside-down.

The once-removed source of this unlikely opera is Prejean's account of her work as spiritual advisor to two convicted murderers awaiting their executions in Louisiana's electric chair in the mid-1980s. In an adroit blend of memoir and advocacy, Prejean's book recounts her attempts to understand and humanize these men, her uphill battle to get them to accept responsibility for their crimes and achieve some kind of personal redemption, her part in the futile legal maneuverings to get their death sentences overturned, her witness of their executions and her wrenching encounters with the parents of both the victims and the condemned. Sprinkled throughout are legal, moral and biblical arguments against capital punishment that, together with her personal testimony, make the book a devastating indictment of the practice and of a society that permits it.

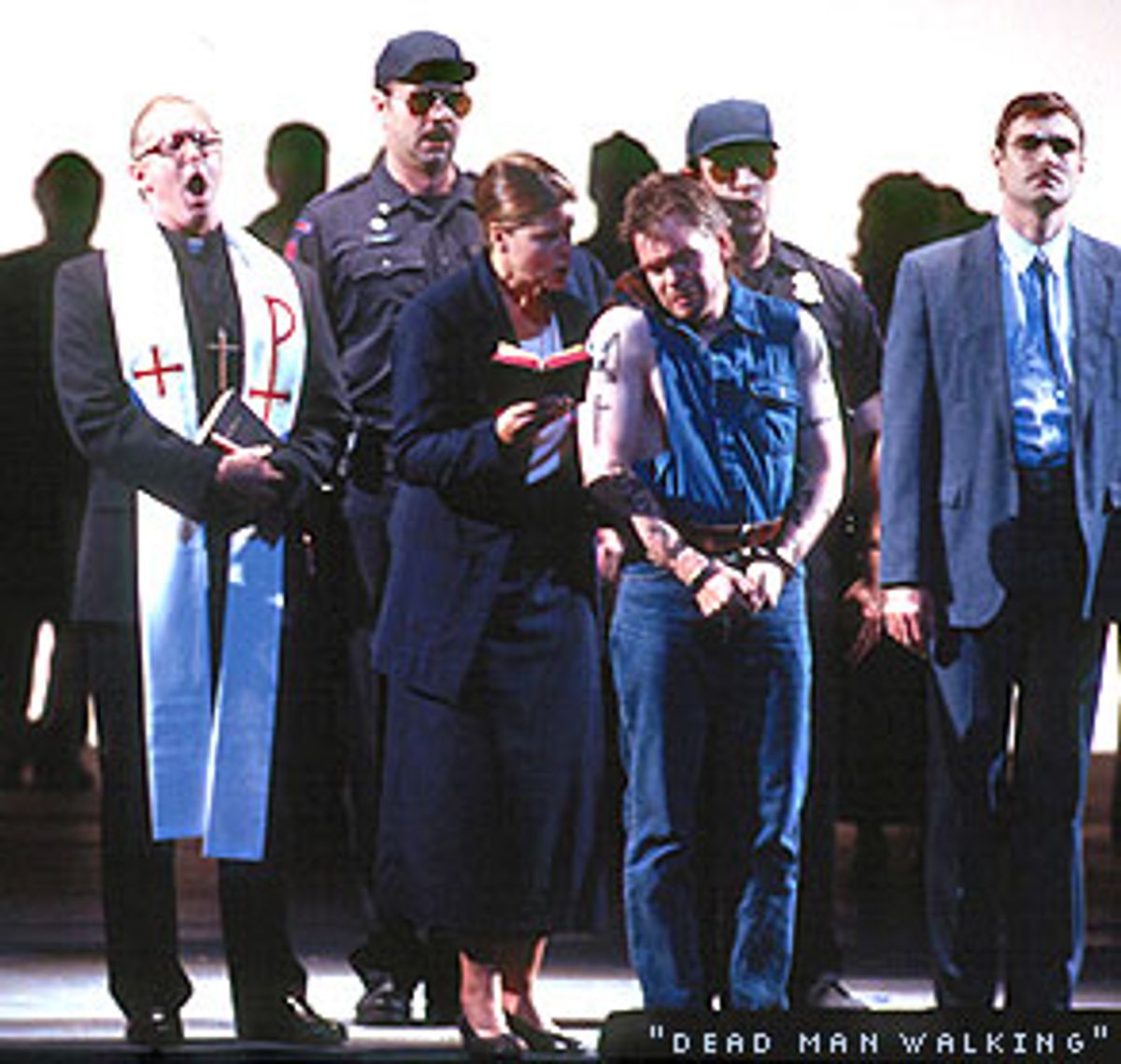

The book, movie and opera all make concerted efforts to convey the heinousness of the convicts' crimes. In perhaps its boldest dramatic innovation, the curtain rises on the crime scene, a midnight forest where two teenage lovers lie naked together after swimming in a nearby lake. They are set upon by the fictionalized Joseph de Rocher (baritone John Packard) and an accomplice. De Rocher rapes the girl, then stabs her to death to silence her screams. The accomplice shoots the teenage boy execution style in the back of the head.

From this opening scene of carnage, which caused audience members near me to gasp, we are transported to a sun-washed scene portraying Sister Helen at work, merrily singing to her young black students in the New Orleans inner city, and then to a lengthy but minimally rendered scene in which Sister Helen drives her car to the prison and expostulates on her situation. Leaving aside the advisability of adorning the stage of an opera house for 20 minutes with a steering wheel and two bucket seats, this is the first scene of several over the next three hours that illustrate a recurrent, possibly inherent problem in staging this story: There's an awful lot of talking in "Dead Man Walking."

The problem of dramatizing a story so bound up with argument and ideas also vexed the movie, which tried to smuggle into dialogue bits and pieces of Prejean's compelling case against capital punishment. What didn't quite work on screen really doesn't work in the opera house. Hands firmly gripping the wheel, Sister Helen slogs through miles of inner turmoil over ministering to a murderer, delivering her thoughts in quasi-recitative passages that repeatedly inspire that immortal question, "Are we there yet?" Once McNally gets Sister Helen interacting with the other characters -- particularly the aggrieved parents of the convict's victims -- things start to pick up.

The music affords us a smoother ride. Heggie's musical language is, like that of most of his young contemporaries, eclectic and familiar; you could say that he occupies the cutting edge of conventionality. But while the various influences of Copland, Bernstein, Berg and other predecessors are clear, the music is good enough to weather accusations of being derivative. With deft orchestrations, he builds tension and delivers climaxes without overreaching. His ensemble writing is superb, particularly when it involves the distraught quartet of victims' parents. The music associated with the crime is particularly evocative: a meandering, ascending chromatic figure that infuses the scene with the same retrospective, haunted grief that characterizes the best of Prejean's own writing.

There are wonderful things about McNally's libretto, though many of them, particularly the comedic scene in which Sister Helen is pulled over for speeding, are the inventions of Robbins' movie. On the whole, however, McNally's admiration for the movie seems to have led him astray in the opera house. In Prejean's book, the condemned is sentenced to die by electric chair. In the movie, as well as in the opera, he faces lethal injection. The prospect of electrocuting a baritone onstage may have been more than McNally and his co-creators could stomach, but it was the horrific fate of death by electric chair -- a device that can take more 15 minutes to finish its work, setting the condemned's head on fire and exploding his or her eyeballs -- that inspired much of the terror and pity of Prejean's narrative.

"Dead Man Walking" premiered with a first-rate cast. The whole group, but Susan Graham in the role of Sister Helen especially, sang with such purity of voice and clarity of diction that the inexact supertitles flashing above the stage seemed superfluous, if not insulting to the singers. Packard conveyed a convincing sense of de Rocher's arrogance and petulance, and can hardly be blamed for failing to bring off the character's rushed redemption. Frederica von Stade, a San Francisco Opera fixture, expertly filled out one of the opera's most successful characterizations as de Rocher's mother, whose breakdowns are that much more effective for her attempts to put on a brave face in front of her condemned son. Theresa Hamm-Smith, in the supporting role of Sister Rose, engaged in conduct unbecoming a nun by stealing each one of her scenes.

The opera ends with Sister Helen's a capella rendition of a spiritual, "He Will Gather Us Around." Introduced with her entrance and heard in bits and pieces throughout the opera, it is the only tune likely to make it home with audience members. The oft-repeated theme is meant to be the opera's emotional lynchpin, charged with summoning all the work's pathos and kindling a redemptive spirit at its otherwise dismal conclusion. But for those of us to whom spirituals sound bloodless and antiseptic when sung in operatic voice, "He Will Gather Us Around" will be the opera's musical undoing. Even if you like to hear Kathleen Battle sing spirituals, even if "Porgy and Bess" is your favorite work in the repertory, the repetitions of this cloying tune act like clusters of redwood trees, sucking up sunlight and starving everything below. Barely one of Heggie's other musical creations can survive next to this melody. It is all-consuming, and if it makes half the impression on you as it did on me, the rest of the opera's fine music can hardly be remembered, much less redeemed.

Musical misfires can do only so much to distract us from the tale of a man facing death, his conscience and a determined nun. But McNally unnecessarily guts the complex question of the convict's guilt, stripping it of vital ambiguities. In foreclosing the possibility that the convict is being executed for a crime in which he took part but was not the principal actor, as Prejean's first convict maintained until his death, McNally robs Prejean's story of one of its principal tensions. We wind up with a clean confession achieved too easily, with the Christian homily that "the truth will set you free" as our consolation prize. Certainly this type of neat, dramatically slack finale is as familiar to the opera house as it is to McNally's Broadway audiences. But in an opera that so gleefully sets aside tradition, that so readily embraces bleak realism over operatic glitz, this adherence to formula feels like a betrayal. For this we endured fluorescent lighting?

Shares