I am a sexual moderate. I have intercourse -- or at least something that involves two naked bodies and leads to orgasm -- three or four times a week, sometimes less. Sex books and magazine articles tell me that's about the norm for a person in my married state.

I don't think of sex when commercials come on TV. I don't get hot when I see Robert Downey Jr. with his shirt off on the cover of Details. And I don't sweat when the "Thong Song" comes on the radio, although I read somewhere that the average person thinks about sex several times an hour.

When I have it, I like sex probably an average amount -- which is to say, I enjoy it very much, but it's not a preoccupation or anything. I do an average range of sex stuff. I'm not a prude, but I have certain things I'd rather not do (like have sex with other people watching) and certain things I enjoy on a regular basis that are so mainstream as to be pedestrian (like the missionary position).

Sometimes I'm in the mood for sex to be an epic and systematic debauchery, but other times I just enjoy it in a moderate sort of way and am ready for it to be over in about 15 or 20 minutes.

I am outing myself here. As a sexual moderate in today's climate, there is a lot of encouragement for me to stay in the closet.

Two recent books -- Elizabeth Abbott's "The History of Celibacy" and Carol Groneman's "Nymphomania" -- point out that moderation has traditionally been the norm. Throughout history, both abstention and enormous desire have ostracized people from mainstream culture. Surprisingly, this happened partly because both nymphomania and celibacy are associated with frigidity, if you define frigidity as a lack of sexual satisfaction. Celibacy is connected to frigidity because so long as it's voluntary, the person is presumably either out of touch with, psychologically incapable of or immune to the urges that plague the rest of the population; nymphomania, because in the first half of the 20th century it was associated with women being stuck in a juvenile, clitoris-centered sexuality that prevented its sufferers from ever achieving the mature bliss of the vaginal orgasm. "It was frigidity that provided the ultimate push-over-the-edge into sexual abandon," writes Groneman of the attitude in the '40s. "Not lascivious desires or hot blood, but lack of sexual satisfaction most often bred nymphomania."

As a moderate, I essentially fit the confused definition of sexual health that led midcentury doctors to treat diagnosed nymphomaniacs with analysis and mood-altering drugs: That is, I want it just about as much as my husband does, so my desire doesn't frighten anybody, nor is anyone calling me a cold fish. But in the aftermath of the sexual revolution, the definition of health has changed. These days, the ideal level of erotic interest (in the popular mind, if not in the medical professions) can essentially be summarized as "Me so horny."

Abbott contends that celibacy is not unnatural and she goes to some length explaining that all the different levels of desire and practice should be socially acceptable. Yet, her long descriptions of hardships endured by the many people forced into abstinence suggest that perhaps there is at least something natural about fornication, if not unnatural about celibacy. Prisoners will suspend their deeply embedded homophobia to fulfill their sex drives, and according to Abbott's book, about 40 percent of Catholic priests -- who voluntarily renounce sex -- are sexually active on a regular basis, especially in countries where celibacy impinges on a man's standing in his community. These figures suggest that even unusually religious people will break their vows to God to satisfy their urges, and that others will suspend prejudice and preference for the sake of a little nookie.

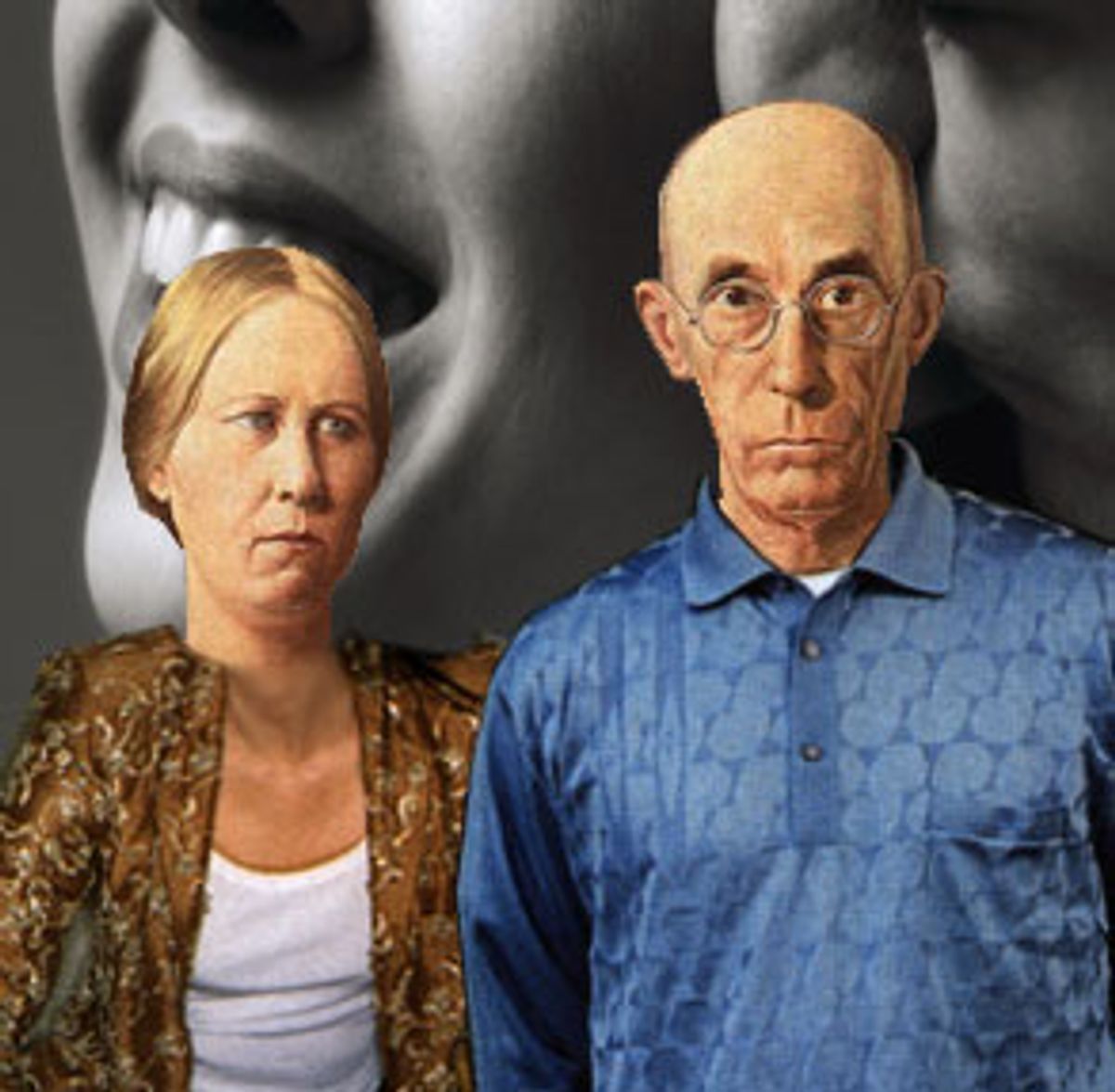

In this sense, "A History of Celibacy" contributes to an idea that we are particularly fond of in this culture today: that the sex drive is very high in human beings, that we'll give up almost anything for sex, that we are basically a very horny bunch of hound dogs, heh heh heh. This idea has something to do with the image of the Marlboro man -- a loner, one with the landscape -- and also with the wet-behind-the-ears adolescent, two icons that are very important to the self-definition of the American male, and that together equate masculinity with a high level of desire. It also has to do with our living in a country that went through the sexual revolution, including the idealization of free love and the explosion of the myth of the happy homemaker.

We Americans like this conflation of ideas, all of which suggest that it's natural to want it all the time, that it's the healthy state of the human body to be ready for it, dying for it, thinking about it in the office, jerking off once a day and generally willing to risk jobs, marriages and money in pursuit of gratification.

No one says proudly that he's only moderately interested. No one says, "I met this guy at a party and he wanted to screw me on the roof deck, but I just wasn't in the mood." No one wants to be thought of as having a medium amount of sex, or of caring about sex only moderately, or of being average in the bedroom in any way. We idealize the heroines of "Sex and the City," the urgently horny Howard Stern, the ultralustful Pamela Anderson, the self-proclaimed hot lovers Angelina Jolie and Billy Bob Thornton.

To be average in bed is to be not good enough, so in talking about our sex lives we have a tendency to portray ourselves as wanting sex all the time, being preoccupied with it in the way our books, music and movies are, being people who know just what to do to satisfy a lover.

Celibates, as Abbott points out, come in two forms: voluntary and involuntary. Those who choose celibacy do so largely for religious reasons, but the last chapter of her book looks at the so-called New Celibacy -- the reclamation of virginity by organizations like True Love Waits, movements that sometimes have religious values at stake and sometimes don't. Books like Wendy Shalit's "A Return to Modesty" and Tara McCarthy's "Been There, Haven't Done That" hold out the promise of marital sexual fulfillment's being increased by maintaining virginity until one's wedding night.

Abbott claims that most of these books and organizations share idealized notions of romance: Celibacy is only a temporary state, to be abandoned when the right mate comes along and everything is made legal. True Love Waits has put considerable marketing energy into making celibacy chic for teens: There are T-shirts, bumper stickers, Christian rock and other kid-friendly products that aim to take the stigma out of virginity. And that's because, despite the emergence of these movements, despite all the P.R. Shalit got, there is still a stigma: To be devoid of sexual appetites or even to repress them successfully is to have one's social standing threatened.

People in our culture wonder about people who don't have sex: Are they strung out? Anorexic? Fanatically religious? Or are they in some way neuter, cut off from their urges because of some childhood trauma or deep personal failing? As Abbott writes, sexuality is equated with normalcy in this post-sexual-revolution age, and abstinence is "tantamount to being branded as an emotional deviant, an errant soul in a world where adult sexuality is a mark of mental health and a measure of social adjustment." Therapists, she notes, even try to restore the fearful or asexual to a state of sexual interest, rather than affirm celibacy as an acceptable way of living. In any case, to be celibate is to be called into question; it is not, in this day and age, normal.

Therefore, understandably, most Americans shy away from proclaiming any lack of interest in sex -- something that's as fundamental to being a sexual moderate as it is to being a celibate. Sometimes, for example, I am just not in the mood, not for days and days. Or I just want to do something relaxed and familiar, rather than something adventurous and especially hot. And I wonder if that means there's something wrong with me. The norm these days is to aver something closer to sexual rabidity -- not only as a marker of liberation and modernity but also as a marker of health, both mental and physical.

I'm not suggesting that the notions of moderate normalcy Groneman describes in "Nymphomania" weren't tyrannical and restrictive. They were. And I'm certainly glad for the Kinsey reports of the late '40s and early '50s, which unsettled -- if not upended -- terms like "natural" and "unnatural" in the study of sexology, and for Albert Ellis' 1960s argument that behavior wrongly labeled "nymphomaniacal" in women was considered completely normal in men and that sexual promiscuity was not a mental illness. However, our current ideal of being always in touch with our desire -- of mental health being partly defined by a perpetual, uninhibited openness to sex that's actually a form of bravado -- is tyrannical as well. It makes me wonder some days if I'm repressed or anhedonic because I'm not in the mood; if my marriage is a hollow shell because we haven't screwed in several days; or if my lack of interest in, say, dildos is a symptom of my self-loathing.

And that's a sad thing.

Shares