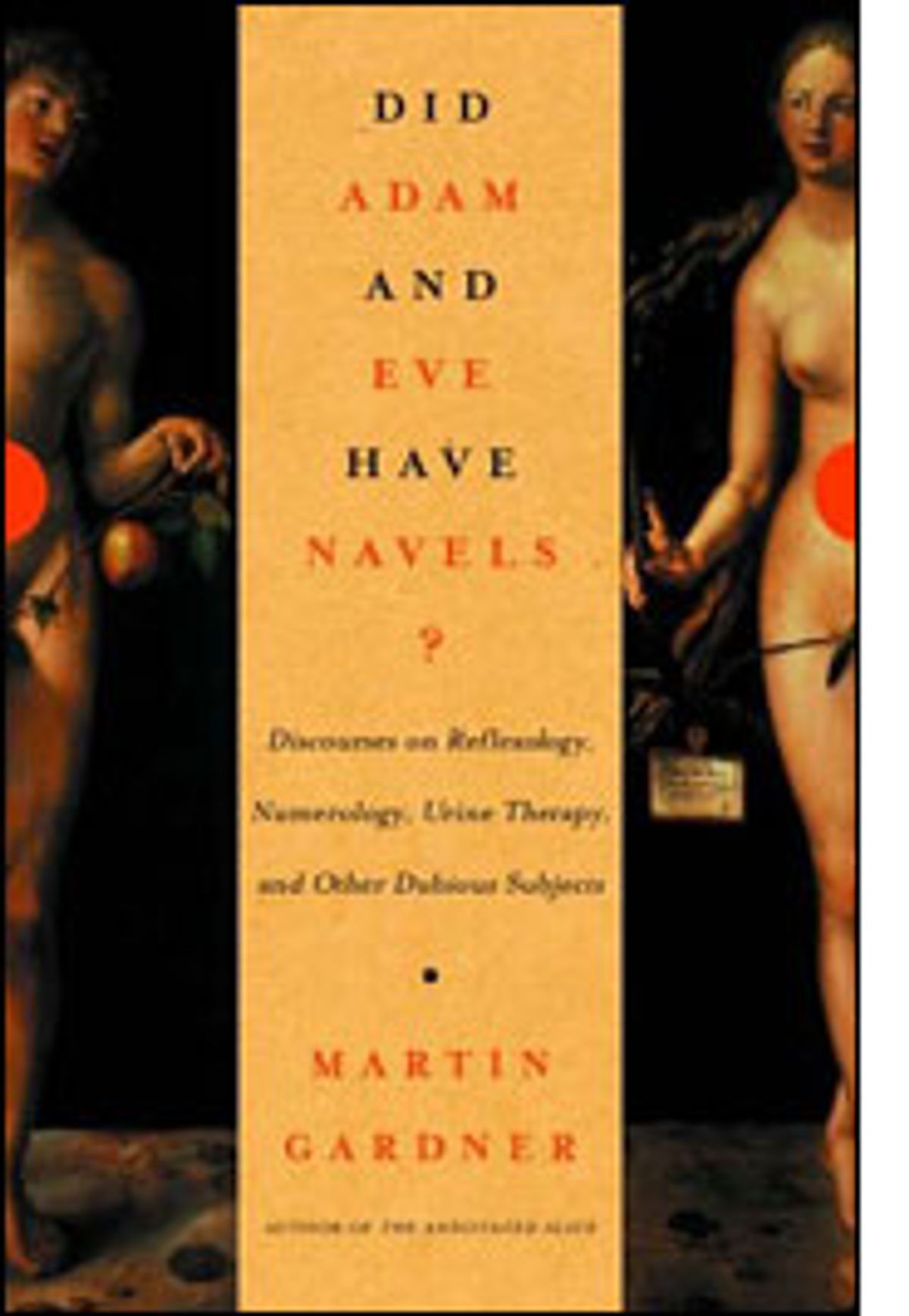

Before cracking open Martin Gardner's latest book, "Did Adam and Eve Have Navels?" I was prepared to be, at best, mildly amused. You know, ho-hum, yet another tome poking fun at religious fundamentalists unable to comprehend the basics of science -- the Scopes monkey trial revisited for the 1,000th time.

How interesting could the topic of Adam and Eve's navels be, anyway? I thought how much more amusing it would be to examine that hot old question -- much discussed at the Council of Trent -- of Adam's penis. (It was decided, given the absence of desire in the Garden of Eden, that Adam's erections were voluntary, that appendage functioning more like his arm.)

Yet it turns out, as Gardner explains in the title chapter, that there have been full-fledged political implications to the question of biblical bellybuttons. In 1944, an acrimonious congressional debate was occasioned by an armed services manual on "The Races of Mankind," which depicted Adam and Eve with those cute remnants of our umbilical cords. Gardner views with amused distaste the idea that some of our lawmakers were worried that the U.S. government might offend that portion of the electorate who take their Bibles literally and hold sacred the unborn status of our original ancestors.

Gardner has his vision trained on all instances of blatant disregard for the scientific method that has been the cornerstone of technical and theoretical progress since Galileo. This colorful collection was culled from the column that Gardner contributes to Skeptical Inquirer, the official organ of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. Perhaps the best-known representative of that organization is magician James Randi, who has often appeared on TV in his role as debunker. Gardner, however, might be considered the ideological father of the CSICOP, since its foundation was partly inspired by his pioneering bestseller, "In the Name of Science."

So Gardner, born in 1914, is no Johnny-come-lately to the debunking game. And with his elegant arguments and fine eye for telling detail, it's no surprise that he has also penned novels and short stories. Add to these qualities the delicious sense of sophisticated fun that one would expect from the author of "The Annotated Alice," who also happened to write the "Mathematical Games" column of Scientific American for 25 years.

He brings those talents to bear in such genially engaging chapters as "Near-Earth Objects." Inspired by the mistaken 1998 news story that a meteor would swoop perilously close to the Earth, Gardner wears an impressive succession of hats -- literary historian, memoirist, film critic -- as he muses (no other term will do) on the theme of cataclysmic destruction. He chillingly concludes by speculating that to fundamentalists "a sudden extinction of humanity would be acceptable. The Biblical Jehovah, remember, is said to have drowned every man, woman, baby, and their pets, except for Noah and his family."

In other chapters he makes clear that some great scientific minds such as Isaac Newton -- who pursued the pseudoscience of alchemy when he wasn't busy inventing the concept of gravity -- have been inconsistent characters who did not always toe the line of pure science. Sketching a fuller picture of Thomas Edison than the usual sanitized version, Gardner sums up his appraisal of the national hero by stating that his "beliefs and habits were those of a crackpot and a bum. Rats lived happy and undisturbed in his laboratory; he often slept in his clothes, because he believed that changing or taking them off induced insomnia; he thought that Richard Wagner was Jewish; he was a disastrous husband and father; he all but starved himself to death because he believed that food poisons the intestines; his own company in Europe coined the cable name 'Dungyard' for him."

Indeed, what sets Gardner apart from the rest of the debunking crowd is that he doesn't just take potshots at the sitting ducks of fundamentalist thought or kooky cults; the sacred cows of science appear equally -- and hilariously -- in his deadly cross hairs. Gardner is always marvelously panoramic and ruminative, whether reporting the spread of the mistaken belief that eggs balance more easily on the first day of spring, pointing out that Newton was a fundamentalist, or discussing the conceptual origins of the Internet in the work of H.G. Wells. And he stimulates these same mental qualities, often useful gateways to creative thought, in the reader.

Schools could do well to interest children in science through Gardner's entertaining volume -- if they don't ban it first. After all, there are plenty of adults out there who don't want their kids exposed to the notion that Adam and Eve had the same bellybuttons we all love to contemplate. And not even a well-reasoned and engrossing book like Gardner's is likely to change their minds at this late date.

Shares