It's Fashion Week in New York -- again!

The Seventh on Sixth festival of fashion may have ended a few weeks ago. But a spate of new ` la mode art exhibits already have clothing-mad Manhattanites, just off the jet from the Paris collections, a-titter about a new curatorial trend that is whipping up haute couture cattiness among art-world insiders.

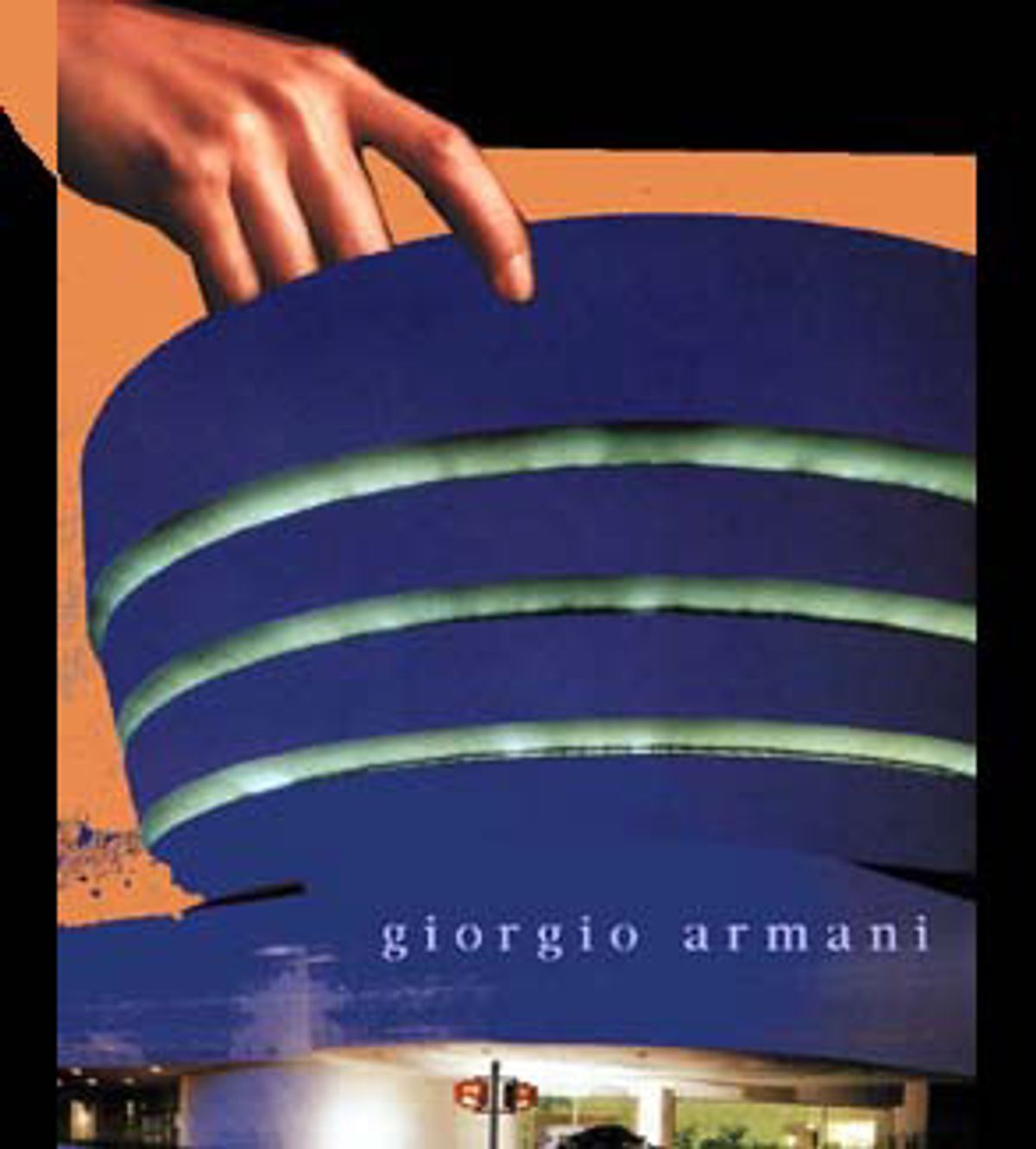

There's the Azzedine Alaoa exhibit at the Guggenheim Soho; the Grey Gallery's show on chic Japanese cosmetics conglomerate Shiseido; "A Century of Fashion" at the Staley Wise Gallery, with works by photographers like Richard Avedon, Louise Dahl-Wolfe and Baron de Meyer; and, most enticingly, the blockbuster Armani exhibit opening this Friday at the Guggenheim, with a "runway" exhibition space designed by theater designer Robert Wilson. The hefty, star-studded Armani exhibition catalog includes essays by Fairchild prez Patrick McCarthy and International Herald-Tribune fashion critic Suzy Menkes, an interview by Ingrid Sischy, baby photos and Armani ads, and tributes from the likes of Ricky Martin, Jodie Foster and Pat Riley. (And this is all months before the Met's Costume Institute gala, co-chaired by Vogue editor Anna Wintour, Oscar and Annette de la Renta and Carolina Herrera.)

Not everyone is happy, however, that the Museum Mile has been transformed into one long catwalk. Some critics are accusing the institutions in question of placing themselves on the auction block, whoring themselves for money and publicity.

"These are very cynical museological decisions, determined to break down the distinctions between art and commerce," says Hilton Kramer, art critic for the New York Observer and editor of the New Criterion. "Frankly, I don't know any serious art critic, art historian or artist -- or serious art collector, even those collectors who wear those clothes -- who regard Armani's suits as works of art."

The New Republic's Jed Perl has also ripped the trend, calling it "just another clever muddle of Dadaism, populism, philistinism and commercialism."

What's especially maddening to these art critics turned fashion scribes is the increasingly close ties between museum exhibitions and their corporate sponsors.

"It's a dreadful development," says Kramer. "In art circles it's creating the impression -- and I think there's a lot of reality to the impression -- that the museum is for sale, and that if you have enough money and if you're an important enough company, you can buy the museum to promote your product."

A month after the Armani exhibition was announced, the Guggenheim revealed the Armani company was making a three-year, $15 million commitment to the museum. (The exhibition itself is being sponsored by the celebrity-saturated InStyle magazine.) The Shiseido corporation donated half a million dollars to Grey Gallery's owner, New York University -- a sizable sum for a university. ("The Grey Gallery will show anything, if a company gives them enough money," sniffs Kramer.) When the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Costume Institute axed a Chanel exhibition because of designer Karl Lagerfeld's insistent curatorial meddling, Chanel promptly canceled its planned $1.5 million donation.

Perl blames money- and fame-obsessed artists and government cutbacks for the funny money relationships. "The market-driven mentality of so many American museums dates back to the 1980s, when Warholism and Reaganomics were complementary art-world forces."

Curiously, Lagerfeld, he of the powdered hair and ostentatious Oriental fan, agrees. Today's exhibitions, he told Talk magazine, have "more to do with promotion and ego trips" than any legitimate interest in fashion history. Of the Costume Institute, he sneers: "They certainly weren't afraid of being commercial. They were afraid I was taking over too much, and they wanted the check rather than me: 'Give us the money and shut up!'"

Harold Koda, the newly appointed director of the Met's Costume Institute and co-curator (with Germano Celant) of the Armani exhibit, dismisses his critics as "Marxist" and defends fashion as art. "Fifty years from now," he argues, "which is going to be the signifier, the image that conveys a sense of our time?"

"If I want the work as a curator," continues Koda, "I shouldn't have to take it out because of [some perceived impropriety]. I mean, it's draconian and stupid. You can't make this simplistic argument. In Japan, corporations are the museums! Yet they're able to do shows that are [considered] pure."

Koda says that as long he maintains curatorial freedom he has no qualms about Armani's ill-timed gift to the Guggenheim. "Art has always been sustained by people in power. Do we [pillory] a Medici portrait because the guy in the painting was a patron and that was self-aggrandizing? Give me a break."

But many worry that art institutions are increasingly victim to the financial excesses and the artistic aspirations of the fashion industry. The pressure for big box-office returns and shows with mass appeal is growing, driven by the financial ambitions of modern art institutions, like the Pompidou in Paris, the Tate in London, the Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim, all of which are involved in aggressive expansions. So, if people aren't interested in paying to see art, goes the philosophy, then give the people what they want. (That was one frequently cited explanation for 1998's hugely popular but critically pilloried and BMW-subsidized "The Art of the Motorcycle" exhibition at the Guggenheim, which is sure to be cited again when the Armani exhibit opens.)

"I know a lot of junior curators are just totally horrified by this," says Kramer, "who are saying, 'I didn't kill myself mastering medieval manuscripts to play second fiddle to some dress designer.'"

Even someone like Koda, a well-respected sartorial scholar who describes himself as a "boring formalist," concedes that the art world is now a buzz-driven industry.

"Art has become so concept-driven, it's not a bad thing anymore. Now you have artists who are manipulating art as commerce. I mean, it's Warhol on steroids! It really has blurred the lines. When you flip through art journals, it's difficult to tell if you're looking at an editorial about contemporary art photography or a Gucci or Prada ad."

When asked about how fashion is driven by money, glamour and politics -- all the things that might seem antithetical to art -- Koda laughs and interjects: "What, as opposed to the art world?"

Shares