With the presidential election three weeks away, it's clear that America has finally decided that the best man for the job is ... a TV character.

NBC's engaging political drama "The West Wing," about a fictional Democratic president and his staff, followed up its Emmy night landslide (it took a record nine awards, including best drama) with a resounding ratings victory for its Oct. 4 season premiere. Twenty-five million viewers tuned in for the episode, doubling the series' average weekly viewership from the previous season. Not only was the show the No. 1 rated program of the week, it brought NBC its highest rating for the time period since 1989. To put it in political terms, "The West Wing" has the Big Mo.

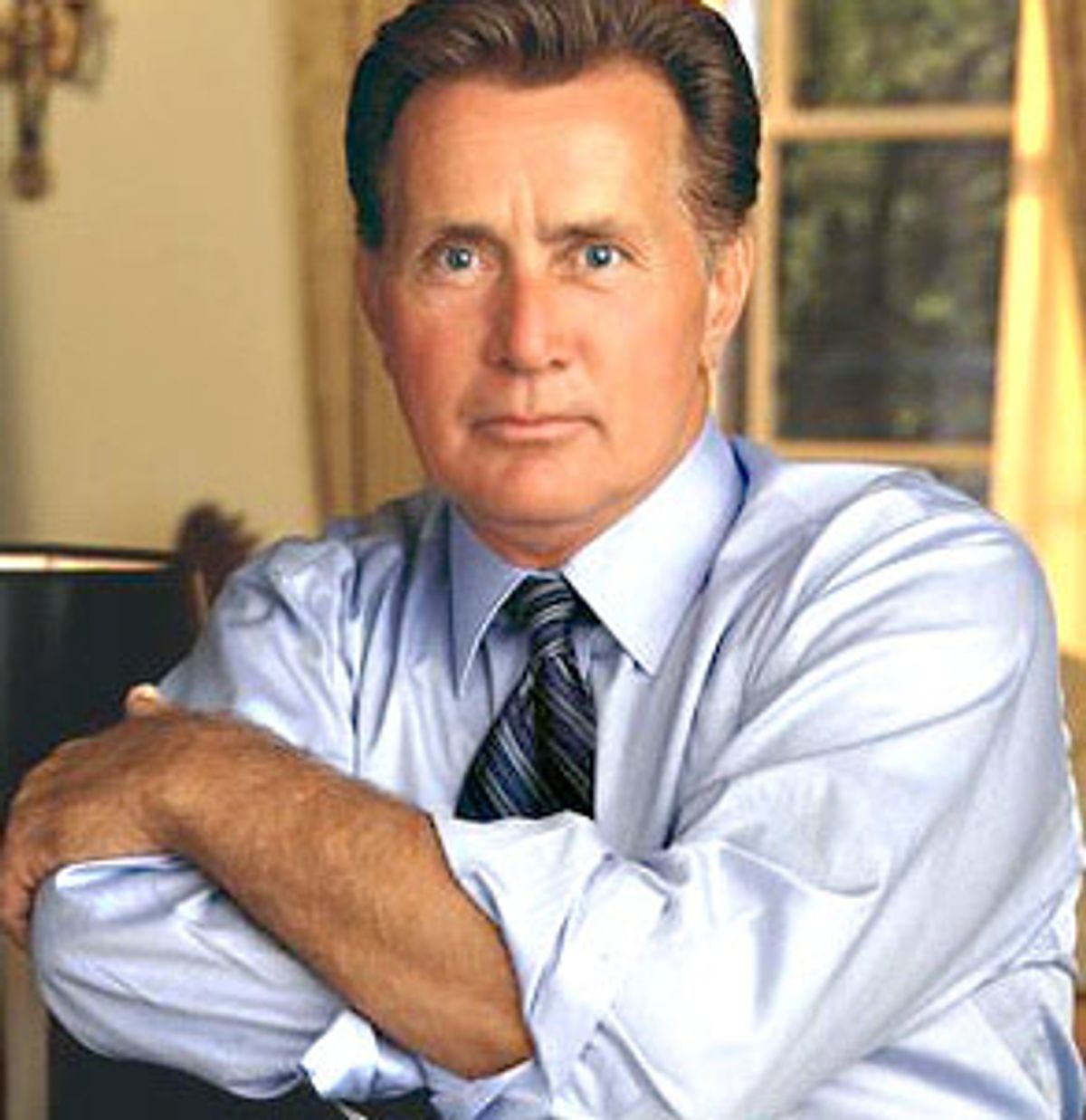

The two-hour episode was a continuation of last season's cliffhanger finale in which President Josiah Bartlet (Martin Sheen) and his entourage were fired upon by gunmen while leaving a town meeting at the Newseum. The president was wounded, as was deputy chief of staff Josh Lyman (Bradley Whitford). The assailants were white supremacists, but they weren't aiming at the president; they were aiming at his African-American personal aide, Charlie Young (Dule Hill), who happens to be dating a white woman -- Bartlet's college student daughter, Zoey (Elisabeth Moss).

Did you catch that last part? In the most popular TV show in America, the daughter of the president of the United States is dating a black man, with her father's blessing. In the most popular TV show in America, the president of the United States is also an undiluted liberal Democrat who is emphatically pro-gun control, is trying to replace "don't ask, don't tell" with a policy that protects the civil rights of gays serving in the military, has come out swinging on campaign finance reform (and he's not all talk either) and has vowed to protect a woman's constitutional right to an abortion.

In the very first episode of "The West Wing," in fact, Bartlet was confronted by a pair of right-wing Christian anti-abortion leaders who sought to use a perceived insult by one of Bartlet's staff members as leverage to force Bartlet to endorse the morality legislation they were pushing for. We've already learned in the episode that Bartlet is religious, and that, in a private crusade, he spent eight months traveling the country trying to discourage teenage girls from having abortions. But, as his chief of staff, Leo McGarry (John Spencer), put it, Bartlet "doesn't believe that it's the government's place to legislate this issue."

And Bartlet dismissed the anti-abortion leaders with a frank speech that was in stunning contrast to the usual timid "balance" of prime-time topical dramas. He parried with them first, quizzing them on the Ten Commandments. Where in Scripture, he finally asked them, does the lord command his followers to mail symbolically mutilated rag dolls to little girls -- specifically, to the president's granddaughter -- who espouse pro-choice views in teen magazine interviews? The Bible and the Constitution are two separate entities, and, by God, he intends to keep them that way, thundered Bartlet. "Now get your fat asses out of my White House!"

Amazingly, this was Bartlet's first scene in the show -- "West Wing" writer/creator Aaron Sorkin had waited approximately 50 minutes into the debut episode to introduce the president. It was a breathtaking entrance (and Sheen played it to the hilt), establishing Bartlet as a political anomaly; here was a politician willing to speak his mind, sharply, without fear of alienating potential backers or risking reprisal from enemies. What a contrast to the obfuscating, hemmed-in men who would be president this campaign season.

In Josiah Bartlet, Sorkin (who also wrote the movies "A Few Good Men" and "The American President") has created the president of a liberal's dreams. And let's be honest about this -- it's hard to imagine "The West Wing" being enveloped in the big, warm media hug it's received since its premiere if the chief executive had been, say, an anti-abortion, pro-gun, pro-school-prayer Republican (although this season, Sorkin has hired former Reagan speechwriter Peggy Noonan to keep Dee Dee Myers company as a series consultant).

Bartlet doesn't chase skirt. He respects the dignity of the office. He comes from Founding Father stock (he's the former governor of New Hampshire), yet bears no trace of silver spoon entitlement. He's an economist by profession, but is capable of putting a human face on the numbers. Bartlet is Clinton with a conscience, Gore with a personality, Dukakis with a heart. Oh, yeah -- and he talks like Truman and looks vaguely like a Kennedy. (Indeed, Sheen played JFK in the miniseries "Kennedy" and RFK in the TV movie "The Missiles of October."). Bartlet is the feel-good Democratic president, the antidote to all the heartbreak of the past few years. He's too good to be true, which is why they call it "fiction."

But Sorkin undercuts Bartlet's perfection by giving him a serious mortal weakness -- he has multiple sclerosis, and his illness has been kept secret from the public and all but a handful of his advisors. He also has an irritating tendency to ramble in conversation until people's eyes glaze over. And, as we learned in the Oct. 4 second-season opener, he had a long, hard climb to the Oval Office.

The episode flashed back to Bartlet's campaign for the Democratic nomination, and a haphazard campaign it was. On the eve of the New Hampshire primary, Bartlet hadn't yet figured out how to stop bogging down in dry economics in his stump speeches. He was surrounded by Democratic Party handlers who wanted him to play it safe and not offend big contributors and special-interest groups. Bartlet was running a distant third in the national polls, far behind the favorite, Sen. John Hoynes (Tim Matheson), a political insider from the South. The depressed shadow of Hoynes -- who eventually became Bartlet's vice president -- hangs over "The West Wing," even though the character has appeared in only a handful of episodes. So beholden to special interests and party bigwigs he can't take a position on anything for fear of jeopardizing his future presidential chances, Hoynes represents politics as usual -- politics as the way it is, in the real world.

But Bartlet -- Bartlet is something else. In that same New Hampshire primary flashback, Bartlet is giving a sparsely attended speech at a veterans hall when a New Hampshire dairy farmer stands up and scolds him for vetoing a bill that would have helped struggling farmers by raising milk prices. This is Bartlet's reply: "Yeah, I screwed you on that one. You got hosed ... I put the hammer to farmers in Concord, Salem, Laconia, Pelham ... You guys got rogered but good. Today for the first time in history, the largest group of Americans living in poverty are children. One in five children live in the most abject, dangerous, hopeless, backbreaking, gut-wrenching poverty any of us could imagine. One in five. And they're children. If fidelity to freedom and democracy is the code of our civic religion, then, surely, the code of our humanity is faithful service to that unwritten commandment that says, 'We should give our children better than we ourselves receive.'" Bartlet stops, for just a moment, untangles his thoughts and starts again. "Let me put it this way. I voted against the bill because I didn't want to make it hard for people to buy milk. I stopped some money from flowing into your pocket. If that angers you, if you resent me, I completely respect that. But if you expect anything different from the president of the United States, you should vote for someone else."

Can you imagine a candidate talking to a constituent that way? A president? The season opener crystallized the Bartlet vision -- the Aaron Sorkin vision -- of politics as a noble call to do good. With a passion that's as charming as it is corny, Sorkin has created a president who puts the greater good above special interests, who remains true to his convictions, who doesn't live in fear of polls or pundits. Bartlet remains something of an outsider, yet his propensity for laying it on the line has earned him enough personal respect to get something done in partisan Washington. Bartlet is the POTUS with the mostest, and it's hard not to get all stirred up by him.

Indeed, the Oct. 4 episode filled in the back story of how Bartlet's inner circle was assembled and it was like watching the disciples getting the great call. In the New Hampshire primary flashback, future White House chief of staff McGarry was already a believer; so was his future communications director Toby Ziegler (Emmy winner Richard Schiff), a deep thinker who had been on more losing campaigns than he could count. But Josh Lyman was working for Hoynes, and he was disillusioned by his candidate's unwillingness to do the right thing -- or anything. Lyman's old school chum Sam Seaborn (Rob Lowe), the future deputy communications director, was unfulfilled too, working as a corporate lawyer finding tax loopholes for giant oil companies. Future White House press secretary C.J. Cregg (Emmy winner Allison Janney) was perhaps most unfulfilled of all, working as a movie publicist for a Hollywood public relations firm, even though she didn't give a damn about movies or public relations. Everything about C.J.'s slouching body language in the flashback screamed, "Kill me now."

In the Oct. 4 episode, McGarry, hoping to recruit Lyman for the Bartlet team, invites him to come to New Hampshire and hear the candidate speak. On his way there, Lyman stops in to visit Seaborn, promising to let him know if Bartlet was "the real thing." A few scenes later, after witnessing Bartlet's response to the dairy farmer, Lyman is standing outside Seaborn's office with a goofy grin on his face, nodding, "Yes." (It's a pretty good inside joke that the real thing -- the president -- is played by Sheen, one of Hollywood's most high-profile political activists. A proud remnant of the old left, Sheen has been arrested dozens of times in anti-nuclear, human rights, civil rights and peace demonstrations; his most recent arrest was on Oct. 7 at an anti-Star Wars missile defense system demonstration at California's Vandenberg Air Force Base.)

"The West Wing" is staunchly in the tradition of the serial workplace drama, like "Hill Street Blues," "NYPD Blue," "ER" and "The Practice" before it. But it's built around a radical notion -- that politics doesn't have to be synonymous with cynicism. Most of the big TV dramas of the past 20 years tended toward battered liberalism and a dark worldview; their heroes were good guys struggling against the tide of disillusionment, dealing with the poverty, crime, sickness and other tragic consequences of political leaders' neglect. "The West Wing" is an optimistic show. It insists that politicians don't have to be jaded or spineless, and that it's not futile for people to get involved in politics or work for a cause. And that's why, at a time when politicians are having trouble lighting a fire under the electorate, "The West Wing" has managed to hook viewers (who are also, presumably, voters).

Of course, "The West Wing" has caught on for TV reasons, too. It's a crackerjack piece of entertainment with smart, meaty dialogue, wonderful acting, richly detailed characters and, for a show about politics, a surprising lack of preachiness. But I think it has also struck a chord with viewers because, like Mulder on "The X-Files," we want to believe. And "The West Wing" gives us a glimpse of what it's like to truly have faith, not so much in one candidate or one president, but in fighting the good fight. It offers a glimpse of what sort of leader we might elect if our political process were about substance, ideas and accomplishment, instead of "character," TV cameras and mudslinging. "The West Wing" makes you wonder if we could ever send a Josiah Bartlet to the White House.

In the series' defining episode, "Let Bartlet Be Bartlet," which first aired last April, Bartlet's staff was distressed over a leaked memo written by a political consultant for one of Bartlet's potential rivals in the next election; the memo detailed the weaknesses of the Bartlet administration, chiefly criticizing McGarry for being too cautious in holding Bartlet back from boldly articulating his principles and pursuing his agenda. In the midst of this crisis, Bartlet's people were also anxious about the downward spiral of the president's popularity rating. The West Wing staffers had gotten caught up in the game, at the expense of the ideals that had brought them to Bartlet's side in the first place.

In that episode, Bartlet has a chance to make good on his promise of campaign finance reform. Two seats open up at the same time on the Federal Election Commission, and Bartlet, at Lyman's urging, wants to appoint two supporters of campaign finance reform. McGarry thinks it would be political suicide, but by the end of the episode he realizes that the leaked memo was right. He is holding Bartlet back. So he presents Bartlet with a note pad on which he has written his new strategy. It consists of one sentence: "Let Bartlet Be Bartlet."

The dirty little secret of "The West Wing" is that it's not a valentine to party politics, despite what Beltway fans may think. Let Bartlet be Bartlet? The only presidential candidates allowed the freedom to be themselves these days are the footnote candidates, the Naders and the Buchanans. In the real world, Josiah Bartlet, with his frankness and his refusal to play ball with the big boys, couldn't get nominated -- let alone make it to the West Wing.

Shares