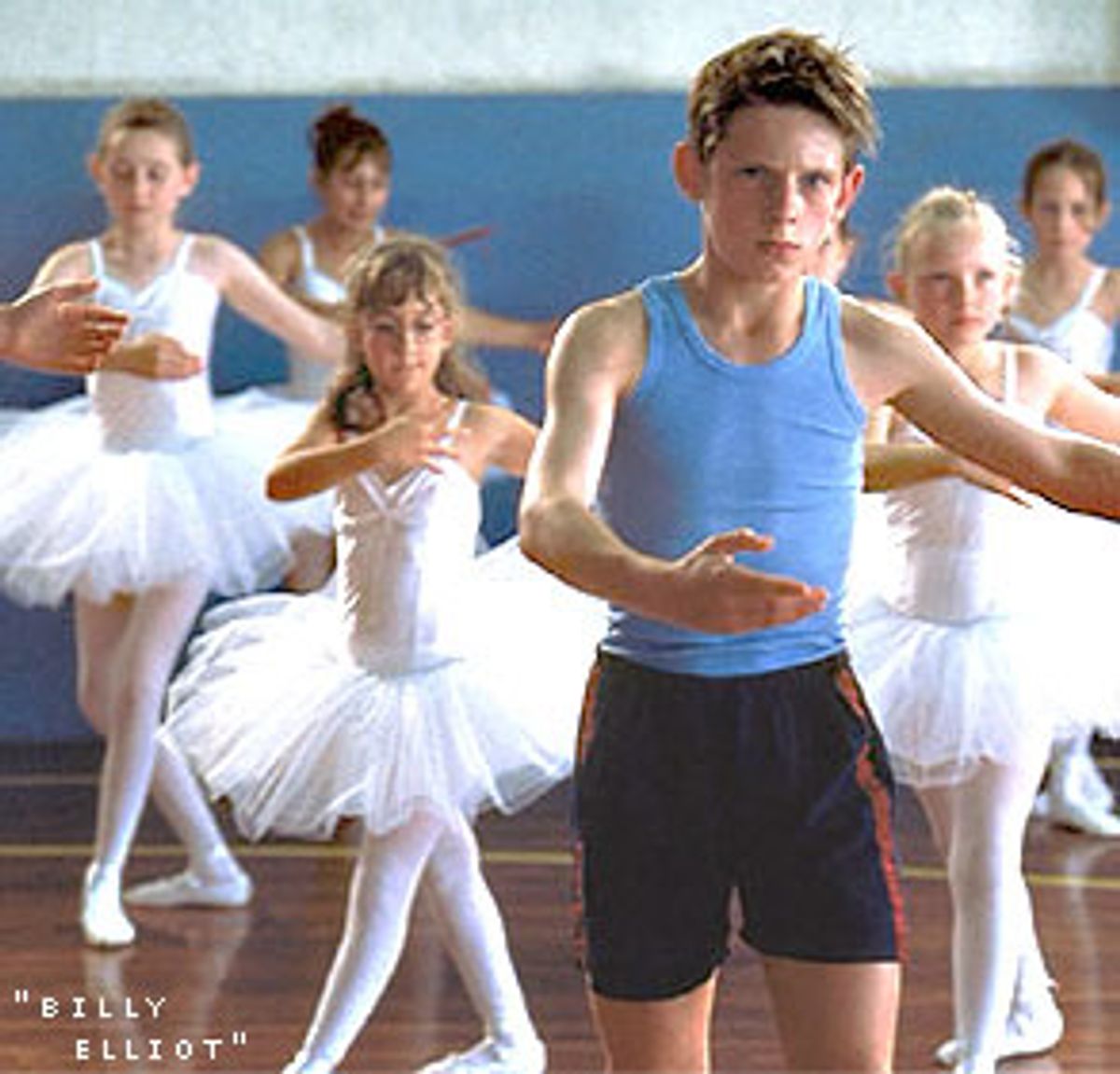

"Billy Elliot," the tale of a miner's son who wants to be a ballet dancer, has what admirers of "Shine" thought it had: an engulfing artistic passion and a varied, veracious and indelible ensemble. It introduces a pair of standout talents -- the director, Stephen Daldry, and the young star, Jamie Bell. In addition, Julie Walters, as Billy's dance coach, pulls off a brilliant reversal of the student-teacher relationship she helped etch so vividly in "Educating Rita" (1983), while theater vet Gary Lewis superbly limns a proud, hardscrabble dad -- the opposite of a stage father.

Movie lovers are accustomed to seeing acclaimed directors from the theater stamp their film work with stage trademarks, using the camera frame as a proscenium and encouraging actors to emote at the audience as if still trying to address the balcony. But that doesn't happen in "Billy Elliot." First-time feature director Daldry, known for London and Broadway sensation "An Inspector Calls," deploys his camera like a magic carpet with just the right amount of grit embedded in the fibers. Instinctively and unobtrusively, he keys his lens to the fluid, funny, unpredictable movements of his soaring star, Bell, who, as the 11-year-old hero, bolts and prances through a depressed northern England town locked in the futile struggles of the 1984 coal strike.

On a publicity stop in San Francisco more than a month ago, Daldry, a lean, dapper man of 40, accepted my compliments but resisted becoming self-conscious about his accomplishments. The movie, he says, came about because "it was written by a friend of mine called Lee Hall, whom I've worked with a lot. I responded to a variety of thematic strands within the piece. It's a celebration of human endeavor and human life against the odds -- pretty much a classic story. It contains the theme of teachers: what goes into the good ones and how, subconsciously perhaps, we betray them. And there's the theme of the grief of the miners strike, which put families in crisis. I've always believed quite strongly in the power of art as the transforming crucible in our lives. The idea of the particular art in this piece being dance wasn't as important as it being art of one sort or another. For Hall, who comes from that area in England, the way out was writing; he went to Cambridge and wrote there."

Since "Billy Elliot" is a movie with a clear, buoyant personality, it's tempting to trace autobiographical connections between the story and its maker and star. But Daldry's own youthful background was bucolic; he grew up in England's Somerset County in a farm community. And if advance publicity tried to link lead actor-dancer Bell with his character, Daldry poohed-poohed that notion, saying, "Any boy who wants to be a ballet dancer will get similar reactions from other boys."

When I interviewed Bell after my talk with Daldry, Bell, who was 13 and in a drama club when he signed up for the movie, explained that he went after the role simply as a plum performing opportunity. What Daldry found in Bell was the rare child performer capable of submerging himself into a character and responding to the process so deeply that this character becomes entirely his own. Slight though he is in size, Bell on film is larger than life -- and that fit with Daldry's view of the difference between theater and film.

"The mediums are not really related," contends Daldry. "It seems to me novels are much closer to the movies than theater is. The actual artistic root is different. I think serious theater is about authenticity. It's about putting real life of one sort or another onstage, within a single authorial voice. It's essentially journalistic, really. So I think theater and television have a much closer relationship than theater and movies. I think that if theater is about our conscious world, then the movies are about our subconscious world, the dream world."

So what may have drawn Daldry most of all to "Billy Elliot" was that it was about a dream "quite literally." At his most inspired, Daldry insinuates dreamlike moments into the daily grime of mine-town life -- as when Billy, after watching Fred Astaire on TV, does his own top-hat dance in the middle of a street.

"We thought that one up," confides Daldry. "Jamie had a stick and was playing around with it as if it were a cane. So we just barked out, 'Anyone know how "Top Hat" goes?'"

As filming went on, dance became essential to Daldry's treatment of even nondance subject matter. For example, the first half of the picture depicts the taunting confrontations between police and strikers, and between strikers and scabs, with an unstressed, organic choreography. You see the forces of Labor and Conservative government enact blood rites of protest and crackdown with the woeful inevitability of a tragicomic folk dance.

"Yeah," Daldry agrees, "and then, in the second half, the backdrop becomes the foreground. Dad has been striking but then he suddenly tries to go back to work, to help Billy, and the background becomes foreground. But the 'design' of that is something that we happened on in the making of the movie. We could plan only certain things. The choreography was the biggest challenge -- the dance generally -- and the other big challenge was we didn't have much money, so we didn't have long to shoot. And we could only work five-day weeks. It was quite stressful."

Was it easier directing young, often nonprofessional actors in this movie than it would have been in a stage piece? "Um, well, yes and no," says Daldry. "I mean, most theater methodology is predicated on the idea of repeated action. That was why 'the system Stanislavsky' was crazy, really, because how do you repeat the 'moment of truth' again and again and again? In movies you don't necessarily have to repeat the moment of truth and the actor doesn't have to take responsibility for the entire evening. The rhythm, the texture, the other actors, narrative structure -- they keep each segment of the action in context, so even the lead actor doesn't have to carry the burden of a piece.

"But I don't think I treated the kids -- certainly not Jamie, anyway -- any different than I treated the other, adult actors. There are two sorts of child actors. You know, there are the ones that basically do what they can -- and basically the roles turn out to be them. And then there are the other lot, which are just proper, grown-up little actors: They can imagine themselves in situations that they have no knowledge of and can make an imaginative leap. Jamie's one of those, so he isn't really raw talent. He's a proper little actor, as opposed to, say, the little girl who befriends him, who has only one way of doing anything. And Jamie, while in character, didn't change; he's a very good actor."

My favorite sequence in "Billy Elliot" depicts a bare-bones Yuletide at Billy's house, where crepe paper lines the living room and every one wears a paper hat. Despite the father's chopping up his late wife's beloved piano for firewood, the family does celebrate, and the sequence strikes a magical balance between melancholy and homespun transcendence. It has a fragile, quiet gaiety.

"Yeah," says Daldry, "and there's no music there, no camera movement. On a scene like that one you've got two options in terms of what you do with the camera. You can let the actors basically run the scene -- orchestrate the scene, rehearse it and just let the camera watch the scene. The other option is to move the camera -- in other words, if Dad starts breaking down, push in. Which is what you'd normally do, so the camera, or the filmmaker, is working the emotion, or at least indicating the emotion. Audiences immediately sense what a push-in means: that the camera movement, as opposed to the actor, is dictating an emotional intensification. So the camera pushing in can prevent the actors from doing anything. If you've got that camera coming at them, then the audience is already thinking, 'Oh, my God, something important's happening 'cause the camera's moving.' Which I think is a cheat. I had certain rules about the filming, like if the camera or the music was pushing an emotion that wasn't there, then that would be wrong, or it would be wrong if you were aware of the camera. I was also worried about an overuse of the camera because, you know, with first films you can often get a self-conscious attempt at style."

But when Walters, Billy's dance teacher, argues with his angry and befuddled father about the little boy's future, Daldry utilizes an almost orgiastic mix of quick cutting and pushed-in angles; then Billy erupts into his own terpsichorean catharsis. "You're picking on exactly the scene that would be the exception," says Daldry, laughing. "That's exactly right."

Did Daldry view the out-and-out emotionalism of the film's second act as a potential pitfall? "No, I didn't note it as a pitfall. No," he protests. "I think that's what we were going for. Most English films work on the idea of 'less is more' emotionally, and I was really interested in the reverse. We wanted to keep it as truthful as we possibly could and not veer off into sentimentality, yet enjoy the sentiment. Sentiment is fine; sentimentality is not. Sentimentality is emotion beyond the fact -- if you haven't earned the emotion, the scenes become generic.

"Now, the emotional orchestration of the second half of the film -- yeah, that took a lot of doing. We did a huge amount of work in the editing and there were many other scenes in there that I had to lose. That was hard to get right. I thought you had to keep banking the emotion and not spend it too early. I don't know how best to describe it -- you keep allowing the emotion to happen, [without] giving into the release."

Daldry's most stirring achievement in the push and pull between emotion and astringency is the student-teacher relationship of Bell's Billy and Walters' Mrs. Wilkinson, which is fractious, ambiguous and never fully resolved. "I love that about it," says Daldry. "Most people have mentors you can relate this bit of the film to; I certainly did. And the problem is, no matter what stage you're at when you're with them, you usually can't take them with you. They often get left behind. It's an unconscious cruelty -- though 'cruelty' may be too strong a word. There's always a slight sense of guilt attached to your great teachers, which gets expressed in thoughts like 'Oh, I should contact them all; I should invite them all.' You may know you have to move on, but it is always quite hard. So I decided not to have one of those 'Oh, my God, it's so fantastic that you got into the school' scenes. And Julie is great. She plays her character a bit jaded. I was lucky with all of the actors. Usually, you have somebody you've got a problem with, and I didn't have a problem with any of them. Lewis, the father, is fantastic. He's only made a couple of films. It's very hard to find English actors of that age who aren't either very busy or very bitter."

After seeing "Billy Elliot" and talking to Daldry, I wondered whether reading about his supposedly artifice-laden theater work had given me a wrong impression of his talents and ambitions. "I teach directing in the theater," he explained, "and one of the things that I always teach young directors is that you've got to know the rules before you can break them. I've spent a lot of time in the theater, so I know how I can fuck about with the rules, as opposed to veering toward an experimental aesthetic just for the sake of it. I do like playing around with what is real and what is not, but the theater itself is an artificial medium -- you're always aware of the artifice, and you try to find the reality within that. Playing around with artifice -- is this real or is this not? What are you watching? Where are you watching? How are you watching? It all seems just like good fun. I don't know whether I would do it anymore, but when I was doing 'Inspector,' which was about 10 years ago, I was interested in that."

For all his skill, Bell is so green that learning the rules and breaking them are equally fun for him. He makes even a multicity American promotional tour sound like a gas: "I had a couple of days to see San Francisco," he offers. "Yesterday I went to Alcatraz. I went to the new ballpark [Pacific Bell Park]. I went to see the Golden Gate Bridge, but I couldn't see it because of the fog. I was a bit cheesed off about that, but we did do enough of the city to say that we've been here."

For Bell, "Billy Elliot" started as a dancing challenge: "Most of the auditions were just dancing," he says. "Just in the last couple of auditions did we read the script as well." When filming started, one of the most difficult tasks was learning how to dance badly. "There was a two-month rehearsal period before we started shooting," he recalls, "and we spent a couple of days on how to dance badly. But it was very hard for me because they put the music on and I would automatically dance in time to the rhythm and they told me I had to dance out of rhythm."

Bell says he's been dancing since he was a tyke: "When I was little I used to get dragged to lots of dance rehearsals and competitions because my sister was a dancer. I used to watch the girls at the dancing class and stand outside the door and try to copy what they were doing. I think I had the rhythm within me already. But when you actually get up and do it yourself properly to a different kind of music, it's quite hard to first catch on to the rhythm and then actually get into it."

Like his director, Bell found his inspiration in the script: "I just read it so many times, I got into the character. I was able to forget that it was about some kid that has, maybe, gone through some of the same stages that I have. I just played it as the character. I only began to think about me and the character being similar when all the people interviewing me said that."

Any red-blooded kid who takes tap and modern dance and ballet instead of playing rugby is apt to come in for schoolyard jibes, as Billy does. What Bell found tougher to master was the mind-set of a working-class family in a strike: "Well, I didn't really know anything about the strike at all," he admits. "I had a teacher on set and she actually taught me about the strike. I asked her what women were doing during the strike, because the film doesn't contain many females. I thought, 'OK, what are the women doing when the guys are on the picket line? Do they worry? Do they listen to the radio all the time? Do they watch TV just to make sure it's not their husbands dying on the picket line?' It was quite hard to realize the background the character was coming from -- that your dad's on the strike and all the rest of that. Part of it was that I'm not in a lot of the miner scenes; most of the scenes I'm in don't really relate to the strike. Stephen had to keep reminding me of the fact that Billy is coming from a background of poverty."

Bell comes from a middle-class, single-parent household: "My mom works in a doctors' [office] as an accountant. She works out all the doctors' wages and stuff like that and patients' appointments." When it came to negotiating a volatile relationship with his screen father, or expressing mourning for his screen mother, Bell relied "on the dialogue in the script. It's written very well."

He and Daldry and the rest of the cast did come up with the occasional improvisational coup. In what could have been a maudlin interchange, Billy hands his dance teacher a letter that his mother wrote for him before she died. He hasn't shared it with anyone else. "Me, Julie and Stephen worked very hard on that scene," says Bell. "It did change from the first draft of the script. In the first draft of the scene -- I read it during one of my auditions -- Billy read the letter out himself. Then, in the second draft, it was going to be Mrs. Wilkinson [who] reads it out. But Stephen felt that it would be touching if Billy knew it by heart. So Mrs. Wilkinson says something that she can't carry on, because she thinks it's too sad. Then Billy backs her up and says something. Then Billy loses his confidence and Mrs. Wilkinson backs him up, and then Billy eventually finishes it, which is the ending. That works very well. I think it shows that he's got emotions, that he's expressing them to Mrs. Wilkinson -- and that he hasn't expressed them to anybody before her."

Ironically, Bell says that in real life he "didn't have a very close relationship with my teachers, because at my old dancing school the teachers kind of have favorites. If you're not a favorite, you don't really get recognized."

A little bit of James Dean seeps out of Bell when he makes such remarks. And his inner rebel explodes, in the film, when he punches a boy who is merely trying to comfort him after a traumatic school audition. Bell admits he related that scene to his experience of "people trying to say, when I just came offstage and I did badly, 'You tried your hardest,' when I thought I hadn't, really. Why are you telling me that? What's the point in trying to comfort me when you're not being honest, stupid? But with Billy, I think the guy touches him and Billy's heard a lot about dancers being poofs and stuff. So he cracks him."

Shares