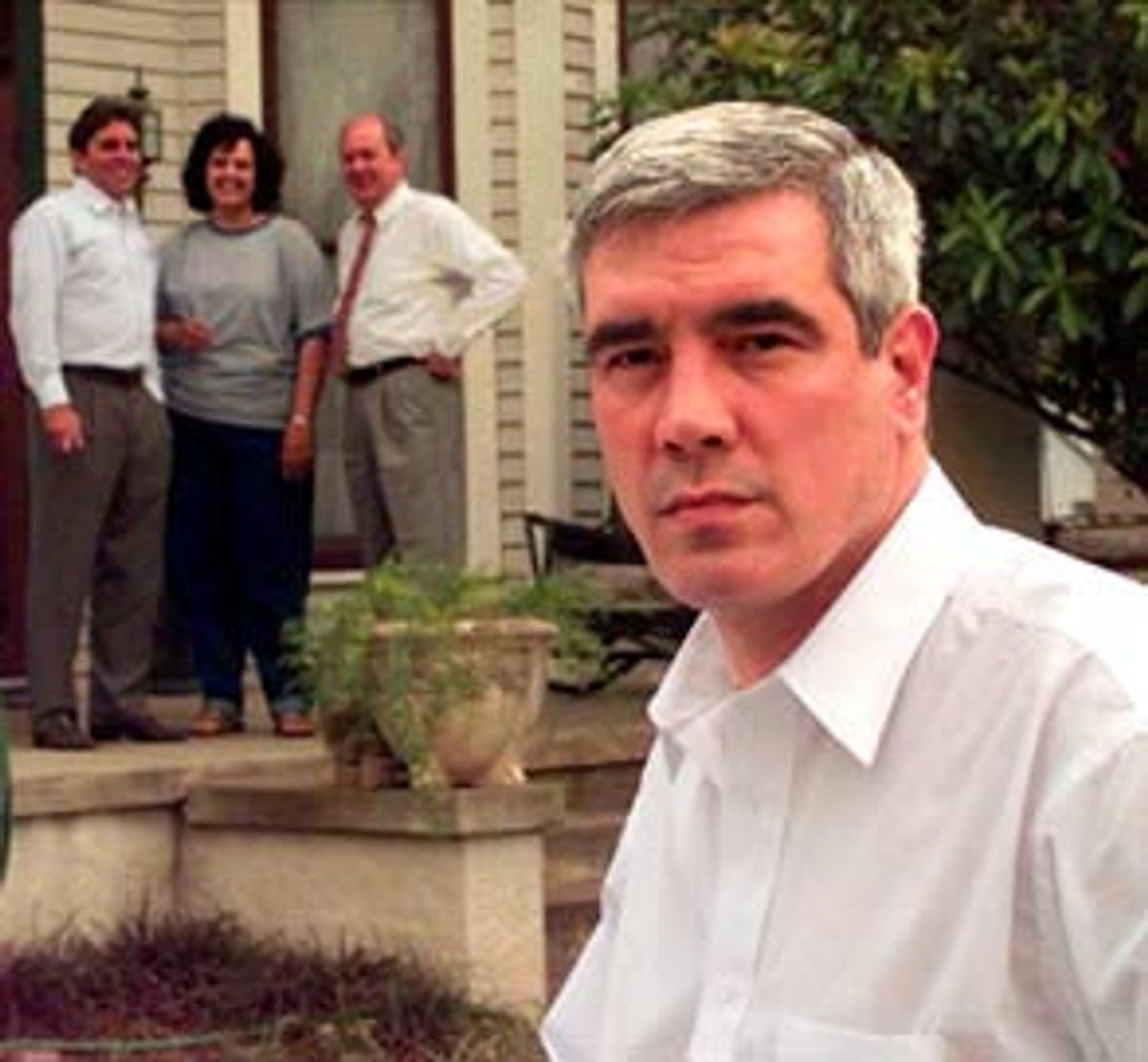

Erik Jensen says tickets are waiting for George W. Bush at will call for a unique New York production later this month. "The reason we have an open invitation for George W. Bush and his wife to come to the show -- there are two free tickets available, any night -- is because we don't think he has any idea what effect what he's done 145 times has on individuals who were, in fact, innocent."

"The Exonerated," a play by Jensen and Jessica Blank, is a series of intersecting monologues culled from their 40 interviews with former death-row inmates who were eventually proven innocent and released. Like the 88 Americans who were wrongfully convicted in capital crimes and have been exonerated since 1973, the play's 12 subjects ("just like in a jury," says Blank) were freed through an appeals process that left them imprisoned on death row for as long as 20 years.

"Each of these cases was an exception," Blank says. "They were not overturned due to the normal workings of the system. These people were freed because of a crusading lawyer working pro bono or a group of journalism students, with the funding of a university, who dug back into a closed case or an investigative reporter who didn't let someone's story die in the public eye for 10 years."

This is Blank and Jensen's first production together; they're getting married in June. Actors and writers, both starred in the just-wrapped independent film "At the End of the Day," and Jensen appears regularly on NBC's "Deadline." The show's rotating cast of actors will include Tim Robbins, Charles Dutton, Edie Falco, David Morse, Martha Plimpton and Vincent D'Onofrio. All participants in "The Exonerated" are volunteers who Blank and Jensen rallied to the cause. Amnesty International USA and other death-penalty activists are on its advisory board.

"These stories speak for themselves," says Blank. "If people's hearts are open and they hear these stories, it's our belief with this issue that they cannot, will not be able to, leave the theater being adamantly and unquestioningly pro-death penalty. They will be moved to question things very deeply, and if that happens, we've done our job."

Their job is a tough one, particularly should the Republican presidential candidate decide to join the audience.

Since Bush began his tenure as governor of Texas in 1994, he has put 145 convicts to death. Kerry Cook was almost one of them. Cook, a former bartender, was on death row from 1978 (a year after the death penalty was reinstated) to 1997. With a number of appeals pending, Cook came within 11 days of execution -- and saw 141 fellow death row prisoners die.

Cook was convicted of the 1977 murder of Linda Jo Edwards, a college student who was having an affair with her married professor. Cook had met her just once -- at which time he'd left a fingerprint on the doorframe of her apartment.

Three months after their meeting, police stormed the club in which Cook was bartending and arrested him. Because the well-known nightspot had gay clientele, investigators came up with the theory that Cook was a "degenerate homosexual" who hated women, alleging that was why the body had been brutalized as it had. (So much damage had been done that the coroner posited that the victim's vagina had been cut out and carried away.)

On the way to jail, one of the lead investigators asked Cook if he "had wings," effectively threatening to push him out of the plane. At the trial, a fingerprint "expert" claimed he could date Cook's fingerprint to be 12 hours old, to the precise time of the murder. He later confessed that it's impossible to date a fingerprint.

Finally in 1996, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals reversed Cook's conviction, stating that "prosecutorial and police misconduct has tainted this entire matter from the outset." Before his final appeal, in 1997, Cook took a no-contest plea to a reduced murder charge and was released. DNA tests conducted two years later matched semen found in the victim to the married professor, proving Cook's long-maintained innocence.

Jensen describes Cook's character in the play as "a 19-year-old in a 44-year-old's body; everything in the world is brand new to him." He addresses the audience, recalling the DNA results coming in: "They said that would be the final nail in Kerry Cook's coffin. Instead, it finally took the nail out."

"When people talk about the death penalty," Jensen says, "they always bring up the victims and the crimes. Well, in releasing the people our show is about, the states have admitted that they never harmed the victims or committed the crimes. What we're trying to do with these innocent men and women is explore the three dimensionality of their experience, not just their incarceration, not just them getting sentenced to death and what that was like, but what their lives are like after as well."

Prosecutors have never pursued the new lead in Edwards' murder. "It's my belief that going after the actual killer would open them up to all sorts of legal ramifications," says Jensen. "It would be embarrassing for the state of Texas."

Cook's is the only case from Texas that appears in the play. "Very few people are exonerated in Texas," Jensen says. Indeed, Gov. Bush's state has freed only seven people from death row, accounting for a mere 8 percent of the total number of exonerated in the nation -- by contrast, Texas carries out 35 percent of U.S. executions. As of last week, 47 percent of all executions this year were in Bush's domain. By the end of the year, Texas is expected to have executed 50 inmates, which would bring its body count to more than all other death-penalty states combined.

The sheer number of executions in Texas, plus the disproportionately low percentage of Texas death-row inmates who are exonerated (3 percent compared to the national average of 14 percent) makes Bush's continued claim that Texas has never executed an innocent man or woman a cold and fuzzy one.

Bush asserted his role in capital punishment during the final presidential debate. "My job is to ask two questions, sir. Is the person guilty of the crime? And did the person have full access to the courts of law? And I can tell you looking at you right now, in all cases those answers were affirmative."

But in Cook's case, "full access to the courts of law" meant a court-appointed defense lawyer who was paid $500 by the state. "And in Texas, you get what you pay for," Cook says in the play.

One of the few safety nets that exists for those wrongly convicted is the window of time between death sentence and execution, when they have the opportunity to appeal. But that crucial window has been closing.

In 1996, President Clinton pushed through Congress what is perhaps the most innocent-be-damned legislation on capital punishment: the Effective Death Penalty Act, which cuts the appeals process by about two-thirds. "Had the act been in effect then, they could have killed Kerry four times," says Jensen. "This is crucial to our play," says Blank, "because it takes about seven years on average in these cases of innocence for the innocence to come out. With the Effective Death Penalty Act cutting that window down to two, three, four years, it puts us at a huge risk of executing innocent people."

In one of the most egregious executions in history, Jesse Tafero was put to death by electric chair by the state of Florida in 1990 -- two years before his wife's conviction for the same crime was overturned. Flames erupted from Tafero's head, and executioners had to pull the switch three times to stop his breathing. State officials attributed the display to "inadvertent human error"; someone had substituted a synthetic sponge for the proven natural one.

Tafero's exonerated wife, Sonia "Sunny" Jacobs (who will be played by Susan Sarandon), is the only female former death-row inmate featured in the play. (Blank and Jensen also included the stories of four wives and girlfriends of the exonerated.) Jacobs and Tafero were sentenced to death in Florida in 1976 for the murder of two policemen at a highway rest stop.

A third codefendant received a life sentence after pleading guilty and testifying against Jacobs and Tafero. He -- the state's star witness -- was the actual killer.

Largely because a filmmaker friend and the horror of Tafero's execution drew attention to her case, Jacobs' conviction was overturned on a federal writ of habeas corpus in 1992, and she was released following the discovery that the chief witness for the prosecution had given false testimony.

By the time she was released, her husband wasn't the only loss Jacobs had suffered: Both of her parents had been killed in a plane crash en route to visit her in jail. She addresses the audience with some of the most unsettling lines in "The Exonerated": "I'll just give you a moment to reflect: From 1976 to 1992, just remove that entire chunk from your life, and that's what happened."

Being sentenced to death for a crime one didn't commit is almost too hideous to imagine. "What we heard over and over again in our interviews was, 'I didn't know that this kind of thing could happen,' or 'I kind of knew from reading about it in the newspaper, but you don't really believe it until it touches your life,'" says Blank.

"One of the things we're trying to do is give people a way to connect with what this is, very directly, and in a way that's heartfelt and human and full -- without having to go through it themselves."

While those who favor the death penalty in this country are still in the majority, popular opinion is waning. A recent national Harris Poll found that support for the death penalty has dropped to 64 percent this year (from 71 percent in 1999 and 75 percent in 1997). It also revealed that 94 percent of Americans believe that some innocent people have been convicted of murder.

"If the system had been allowed to work how it normally works," Blank says, "with state-provided defense attorneys, etc., all of our subjects would be dead. Every single one."

The play, directed by Bob Balaban (who appeared in the recent film "Best in Show") premieres with three benefit performances (Oct. 30, Nov. 6, Nov. 9) at the Culture Project at 45 Bleecker Theater in New York. Half of the proceeds for these shows will go to the exonerated people whose stories appear within. The other half will go to organizations working to overturn wrongful convictions: the Center on Wrongful Convictions, the Innocence Project and Centurion Ministries (a New Jersey pro bono law organization).

It runs one hour and 15 minutes -- the time it would take for Bush to review five clemency appeals.

For tickets to benefit performances and information on the full run in the spring, contact the 45 Bleecker Theater box office, 212-529-4530.

Shares