Scenes from a dot-com dynasty family gathering:

Scott (ex-son-in-law of the family's wealthy patriarch): "Far be it from me to try to be included in a family discussion. I learned my place long ago ..."

Dorothy (ex-wife of Scott): "You also ruined any chance of being a part of this family a long time ago."

Scott: "Well, Dorothy, I am ready. Let 'er rip. Give it your best shot. I am ready for my tongue-lashing."

Dorothy: "Who is the new 11-year-old you are fooling around with now?"

Scott: "Actually she's 5 years old and her name is Gametech.com."

Outtakes from a new prime-time, Silicon Valley soap, implausibly populated with "Baywatch" beauties and pumped programmers? Dialogue downloaded from an Internet sitcom? Nope. Scott and Dorothy are actors in a scene from "Grandpa's Little Secret.com," a play conceived with a very special audience in mind: the families of the superwealthy.

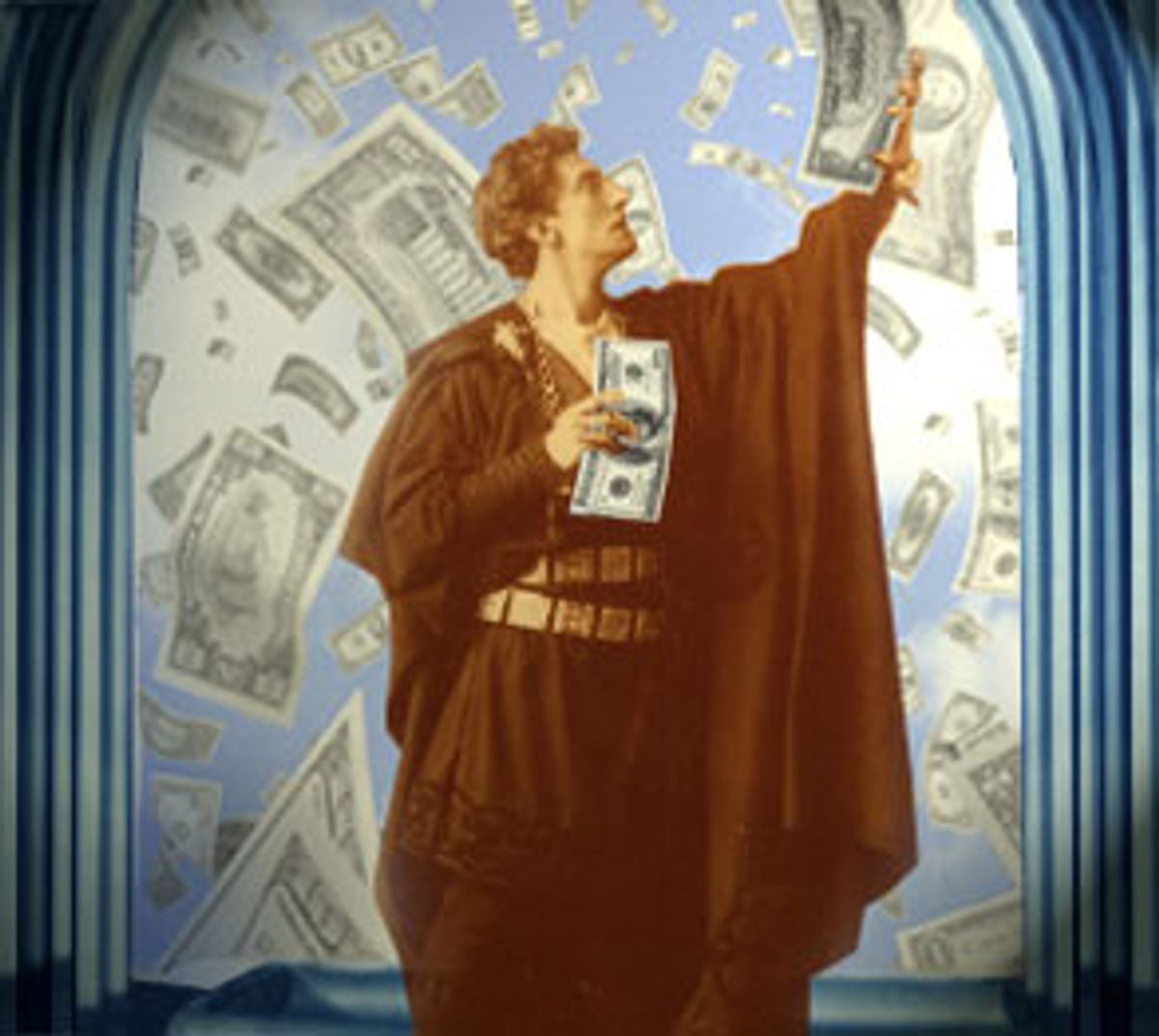

Not what one might have expected from David Kersnar, director, playwright and co-founder of the famed Lookingglass Theatre Company. But in an era in which national funding and patronage for the arts have been all but gutted by Bible-thumping senators, Kersnar has come up with a way to continue doing what he and his partners are good at, and still keep his family out of the poorhouse: Shaking the Tree -- a company formed specifically to produce plays for the viewing pleasure, and instruction, of wealthy family audiences.

Kersnar and his colleagues at Shaking the Tree are commissioned to write and direct plays that teach wealthy families how to get along. The commissioners are usually financial institutions seeking to minimize the damage that their rich clients tend to inflict upon themselves through family feuds and bickering. So the income generated by Shaking the Tree is considerably better than what Kersnar is used to -- sometimes five or six times what he made as artistic director at Lookingglass. In addition, the money gives him the financial freedom to take on other, less remunerative projects.

And the plays work.

"I have seen the light bulb go off, the look on people's faces when what they're watching resonates with some problem they've been grappling with. It's a really effective method of education," says Kersnar.

The "morality" plays that Kersnar and his colleagues at Shaking the Tree construct to teach wealthy families how to get along aren't exactly like the final scenes from "Hamlet." They aren't designed to produce hair-raising moments of personal revelation or peel back sinister motives. Instead, they gently prod their audiences into self-recognition via encounters with archetypal characters and scenarios -- like the prodigal son reluctantly primed to take over the family steel mills, or the mutinous granddaughter whose choice of badass boyfriends is not exactly to her grandfather's taste.

The key here is not the details but the universality of the underlying issues. "Rivalry, fairness, trust and communication -- these are concerns of everyone," says Kersnar.

"Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me," F. Scott Fitzgerald once wrote. "Yes," Ernest Hemingway riposted, "they have more money."

Different or not, richer or not, they also have families. And families -- no matter what the price tag -- have the potential for money squabbles, resentments, politics and just plain old difficult behavior. The difference in rich families, though, is in the Carnegie or Mellon scale of their disagreements. When millions or even billions of dollars are involved, often it's not just the family that is affected. Many wealthy families have philanthropic foundations set up to channel money into worthy causes. So family decisions can have a profound impact inside and outside the family.

"Wealth is popular culture," says Kersnar. "One of the things that wealthy families grapple with is a keen sense of stewardship or responsibility about their money or their companies ... Money just amplifies, really turns up the volume on, the communication problems that families encounter."

Olivia Boyce-Abel should know. Members of her family sued and countersued one another for 13 years, striving for control of her mother's large estate. "We only recently settled the matter," says Boyce-Abel. "I honestly believe that if my family members had experienced one of these plays, it might have changed things dramatically."

As a consequence of her own experience, Boyce-Abel has become a professional facilitator for estate planning and wealth transfer, and serves as an advisor to Shaking the Tree.

"What I've learned is that every family has to deal with communication issues," she says. "But in our society, money is just about the last taboo. Nobody wants to talk about it."

So the actors in a Shaking the Tree production do it for them. But the show doesn't stop at the edge of the stage. Unlike conventional theater aimed at corporate audiences, the Shaking the Tree "case studies" are interactive. At the end of a production, the audience is encouraged to pose questions to the actors while they are still in character. Audience members might ask what a character's motivation was for behaving a certain way toward another character. They might even ask technical questions about inheritance or charitable foundation matters.

"The actors are trained to be able to field financially technical questions as well," says MaryAnn Fernandez, who is a vice president in family education for Chicago's Harris Bank, one of the original sponsors of Shaking the Tree.

She heard about the novel, interactive theater work that Kersnar was doing in public high schools, teaching kids about AIDS and drugs. Fernandez, who has also helped organize "wealth management" conferences, thought the technique might work with her wealthy clients.

And even though the case studies are geared more for Wall Street war rooms than the Great White Way, Kersnar doesn't skimp on production. The scripts are complex and carefully plotted, sometimes taking up to a year to write and produce. Kersnar uses only professional actors, and they are costumed and made up -- all the way down to the right nail polish -- as persuasively as they would be in a Broadway play.

"We try to make it look like a real family," says Kersnar. "Everyone comes to the table with a different agenda and motivations. There's never just one bad guy."

As a result, audience members can feel detached enough from the characters to be moved by them, without being offended.

"It was a really profound moment when an audience member, a daughter of a wealthy family, who felt she had been treated unfairly by her father, stood up afterward and addressed questions to the actor/father figure in the play with the same intensity as the actor/daughter's character had addressed him," says Kersnar.

A case of life imitating art, perhaps, but also a demonstration of the power of art to reach into the heart of its spectators. Rich or poor, there must be a moral in there somewhere.

Shares