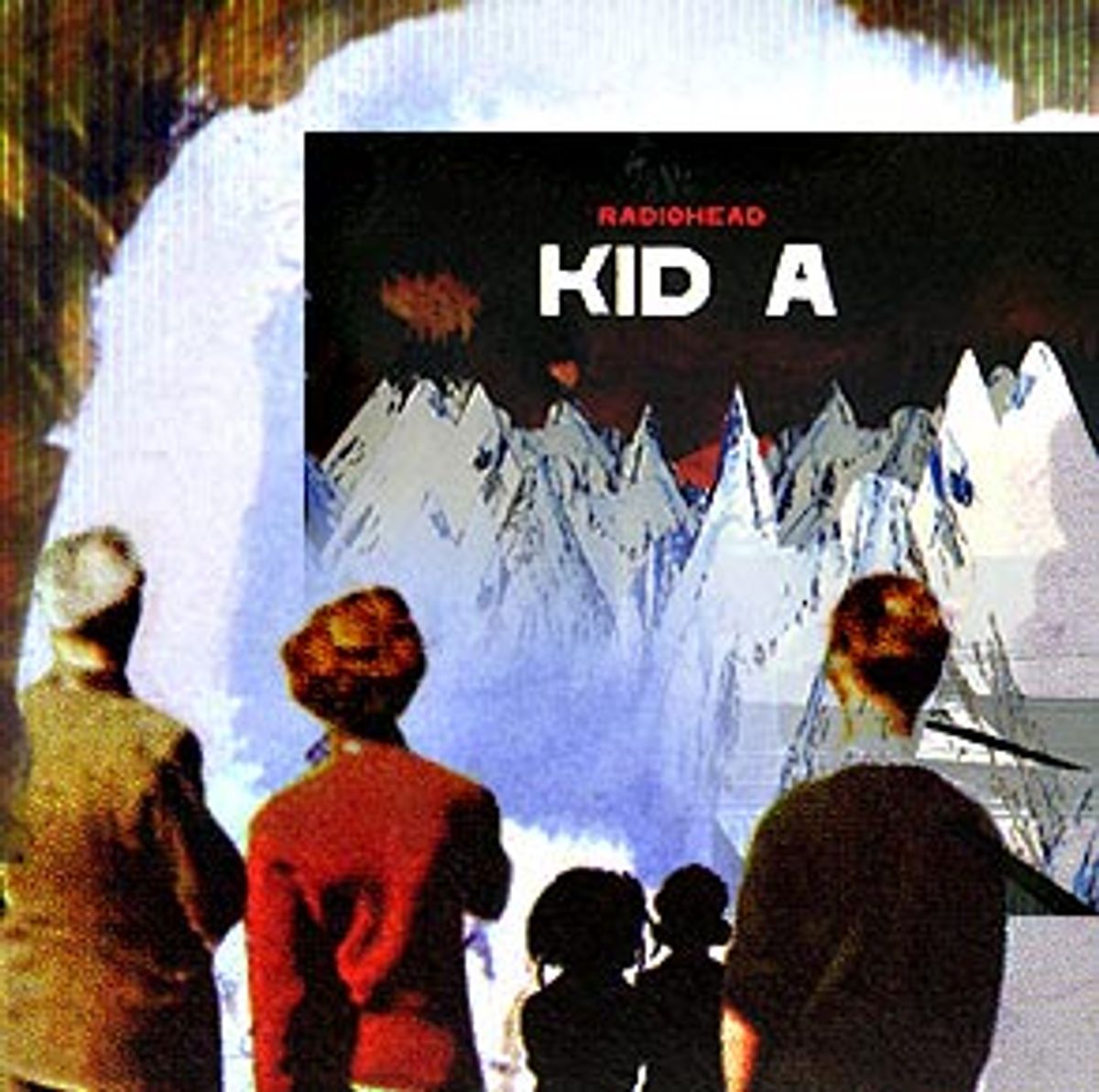

Andrew Goodwin: The critic Theodor Adorno, dismayed by the possibilities for classical structures in a broken world, once argued that "art of the highest caliber pushes beyond totality towards a state of fragmentation." He wasn't writing about rock music in the 21st century. And he didn't write the liner notes for "Kid A." But his words were, as ever, prescient in the extreme.

Alongside Oasis, Elastica, Pulp and Blur, Radiohead were one of five candidates to head up the so-called British Invasion of the 1990s, and if Blur's Damon Albarn isn't choking on his press cuttings right now, I for one will be surprised. Like Blur, Radiohead took one look at "success" and decided to rewrite the rule book.

Think about it. Elastica? Six years to follow up their debut album, and they come back with ... more of the same. Pulp? The inspiration for a thousand sad bedroom soliloquies have been silent for over two years. Oasis? Their implosion was as ugly as it was predictable. Only Blur and Radiohead have lasted the course; and their tactics, like U2 before them, consisted of following up a brace of smash-hit records with a barrage of dirty, spaced-out noise.

To read the reviews, you might imagine that Thom Yorke has invented a totally new kind of music, rewritten the rules of tonality and taken the tools of multitracking to a new level. He has done no such thing. That Yorke has been listening to Aphex Twin is no secret -- the influence of Richard James on this material is transparent. If you are a rock fan looking for new kicks, for something more shocking than the sound of the Gallagher brothers disappearing up their own Beatletudes, then "Kid A" will surprise you.

Otherwise, you will hear an uneven collection of songs weighed down by a paradoxical combination of overambition and underproduction. Some of it is brilliant -- expect "Idioteque" and "Optimistic" to feature in Radiohead set lists for years to come. Some of it is mundane: Listen to the faux-jazz screeching of "The National Anthem" next to the inspired honking of Primal Scream's similar exercise, "Blood Money" (from "Exterminator"), and be embarrassed -- be very, very embarrassed.

The first five notes of the first song, "Everything in Its Right Place," seduce so compellingly that you find yourself listening to the entire album just for the thrill of going back to the beginning. And they also sum up the whole gig. A magical hint of a 1970s Fender Rhodes electric piano lures us in, but with enough synthetic edge to announce something beyond nostalgia. Is it old? Is it new? No, it is something borrowed -- the oldest trick in the Book of Rock. This is the Art Move. Radiohead have replaced rollicking power chords and anthemic stadium chants with ambiguities and fragments. This is the pop equivalent of cinema's Dogme 95 and Brit Lit's New Barbarians -- strip it down, sort it out, detonate the bombast. It is a new thing, and an old thing -- the album as its own remix.

The lyrics are a Rorschach test. What do you hear? "I've lost my way." "You can try the best you can/The best you can is good enough." "I'm here in the studio, suffering for my art/My bandmates are down the pub, drinking beer and playing darts." These lines quite possibly exist somewhere in the mix, buried beneath backward-masked voices, clapped-out beat-boxes and arrangements that suggest, rather comically at times, that the rump of the band repeatedly abandoned Yorke and his producer Nigel Godrich in the middle of a song.

The Beatles invented the (modernist) Art Move. And indeed, "Kid A" does bear comparison with "Sgt. Pepper" on at least two counts. First, it is the most anticipated release in a decade -- albeit for a lost tribe of rock fans whose numbers and confidence in themselves have declined precipitously. Second, "Kid A" is a fine and confused piece of work endangered by the overwrought criticism heaped upon it. We should not blame Yorke for this; we might want to have a word with the Radiohead PR machine, but they, after all, are only doing their jobs. Probably this is nothing more than a hackneyed concept album about cloning -- 40-something minutes of music to follow up on 1997's seven-minute epic, "Paranoid Android."

Soon enough, no doubt, Radiohead will surprise us one more time, with a grungy, in-your-face, hook-laden Rock Move. Meantime, there's Poor Thom, fretting on his guitar, strutting at the mike. He's consumed with anguish about his role as the savior of rock -- I must zig when they zag, he thinks, determined not to let stardom undermine his mission to shock. But his fears are unfounded. Radiohead are a good band, but they're not that important. "Kid A" is a fine album. Rather than losing sleep, Yorke might just realize that until he writes a record as strong as "Definitely Maybe," "Parklife" or "Different Class," the anguish is all for naught.

Michelle Goldberg: Until I heard "Kid A," I thought Radiohead were overrated. Sure, I was enraptured by the supersaturated pathos of "Fake Plastic Trees" from the 1995 album "The Bends," but except for the rushing triumph of the song "Let Down," the much-heralded magic of "OK Computer" eluded me. When that record came out there was a lot of hype about it making rock relevant again. Maybe because I'm part of the first generation in decades that's not defined by rock -- since, that is, its death doesn't presage my own -- I've always thought that if rock needed to be saved so badly, perhaps it didn't deserve to be.

"OK Computer" was celebrated in part for articulating a futuristic, dystopian anxiety, but drum 'n' bass, hip-hop and trip-hop have been doing that for years. I suspect part of the reason so many rock critics swooned over the album was because it took a contemporary sense of dazed, pained disorientation and expressed it in an old, comfortable idiom.

On "Kid A," though, Radiohead have reworked their musical language altogether. The record is a panicked, gritty, gurgling mélange of droning rock, electronic effects and jazz freakouts, full of strange, aching beauty. Unlike musicians such as Tori Amos and Madonna, who have simply injected electronic beats into their work to bring it up to date, Radiohead have created something that transcends fashionable pastiche. There are moments where "Kid A" recalls other records -- the lullaby synth melodies on the title track are intensely reminiscent of the genius German electronic minimalist B. Fleischmann, while the hypnotic guitar grind and wild horn stabs of "The National Anthem" are pure Death in Vegas. As a whole, though, the album sounds like nothing else out there, at once dazzlingly experimental and intensely lovely, delicate and grandiose.

Yet while "Kid A" is a big stylistic departure for the band, it captures the same sense of vulnerability and paralysis in the face of frenzied, overwhelming change that coursed through "OK Computer." It's more powerful, though, because here the terror and yearning in Yorke's reedy singing is echoed so powerfully by the music's very structure. On the first song, "Everything in Its Right Place," his voice seems to be struggling through something viscous and suffocating, while fuzzy echoes, funereal keyboards and warped, choppy vocal samples conjure confused ennui. It embodies the insomniac, brain-whirling feeling that's one of the worst side effects of living at unprecedented velocity.

The song "Kid A" is similarly both unnerving and stunning. With its beguiling toy-piano melody, diaphanous sound washes, submerged drums and robotically processed vocals, the song combines icy bleakness with tenderness, suggesting a beloved child reluctantly brought into an unforgiving world. Again on "Idioteque," which begins with a tired break beat but turns ravishing with the addition of Yorke's slurred, devastated, looped and layered singing, Radiohead render creeping unease and desolation incandescent. I'm reminded of Joy Division, another band that alchemized gloomy, banal alienation into crepuscular beauty. "Kid A" is one of the loneliest records I've heard in ages. Perhaps because of that, it's also one of most comforting.

Joe Heim: The critics are dead wrong when they say Radiohead's "Kid A" does not quite measure up to its predecessor, "OK Computer." In more ways than one, it is every bit as mediocre. Ponderous, self-absorbed and ultimately stultifying, it's a sucker punch that mixes a few brief shards of brilliance with a mostly boring collage of gratuitous electronic noodling and lyrics that range from vague to vacuous. In fact, they are less lyrics than mutterings. "Yesterday I woke up sucking a lemon," the band's lead singer and primary architect, Yorke, repeats through a burbling swirl of atmospheric noise on "Everything in Its Right Place," the album's first track. On "Optimistic" we get the incantation "You can try the best you can/The best you can is good enough."

Hmm.

"Kid A" is not about lyrics, of course. It is an imaginative thematic screed against consumerism and the increasing technological manipulation of humanity. Or at least that's what its apologists insist. The critics and adoring fans point to the album's hidden sonic nooks and delicate spacey flourishes as proof that there is much here to be discovered. They argue that this is a recording that slowly reveals itself. That to understand it requires patience, flexibility and openness.

But the all too speakable truth is that "Kid A" is imaginative only in the number of ways it discourages repeated listening. It is not particularly inventive or groundbreaking and the only there there is what the listener brings there. That's not an innovative musical breakthrough; that's a Rorschach test.

Which isn't to say the album is without a few breathtakingly good moments. The caterwauling free jazz conclusion to "The National Anthem" is vigorously rebellious. And "Optimistic" provides some sense that Yorke and company have not forgotten how to rock. That's the tradeoff with Radiohead: The band can occasionally produce transporting music, but listeners must endure excruciating drudgery and torpor to hear it.

It is heresy of course to speak ill of this band. A single doubting word is a call to arms. But there is no question that Radiohead are the most vastly overrated band of the past decade. That is both their fault and the fault of a coterie of critics and their followers who are determined to anoint any band with more than just a flicker of promise as the saviors of rock 'n' roll.

Radiohead simultaneously revel in the tag and abhor it. "Kid A," like "OK Computer" before it, is a "we don't want to be rock stars" record. It is an anti-record really. But ironically, in its attempts to refute its conferred star/savior status, the band is making unnecessarily grandiose statements. "Kid A" is a damning of categories, a thumb in the eye to expectations and a strong rebuke to the ever-increasing commercial nature of popular music. Choosing those product-unfriendly values may be an admirable decision, but that doesn't somehow make the band great.

Andy Battaglia: More than any other rock band working nowadays, Radiohead know how to push buttons. Quite literally, they push the buttons that turn studio software into beautiful soundscapes with the skill of haute electronicists. But more than that, they push the buttons of an implacable musical audience for whom the notion of the "important" record is something to scoff at. Chart-topping albums aren't supposed to matter as much as "Kid A," and Radiohead seem almost combative for so sheepishly making one that does. Part of this has to do with their love of irony and coy ways with the press, but it also speaks for a musical climate in which a word like "important" can hardly be uttered without scare quotes acting as a safety net.

If "Kid A" is important -- and I think it is -- it's because it was artfully constructed by a rock band that has warmly embraced the most determinably obscure movements in electronic music these days. Lots of rock bands, like Stereolab, Broadcast and Pram -- not to mention insanely progressive R&B producers like Timbaland -- are mining similar ground. But "Kid A" is cartoonishly difficult in ways otherwise exercised only in the most arcane realms of the techno sphere, where militantly elusive figures equate impenetrability with progress. That world is full of intrigue, all catty micro-genric infighting and scandalous ideological defections, like Kid 606 pissing on his peers in the Intelligent Dance Music scene, Photek ditching drum 'n' bass on his new album or Aphex Twin giving up on music altogether. But those disputes rarely amount to anything more than scientists arguing over hypothetical contingencies in string theory to people who have things other than music on the brain.

This is where Radiohead comes into play. It goes without saying that it'll be a long time before some act from the white-hot minimal techno scene in Cologne, Germany, debuts at the top of the Billboard chart. But when "Kid A" did, it brought a lot of ideas out of their willfully hidden corners and blew up microscopic movements into widescreen relief.

None of this would be anything more than novel if the members of Radiohead weren't almost scarily good electronic musicians -- and not just for a rock band. The sounds and textures on "Kid A" are top-of-the-line in every way, taking cues from the electronic underground but also expanding on them and smartly assigning them more immediately affecting, song-based duties. Radiohead borrow from the electronic underground, then outrun it by relegating aesthetics to a secondary science. The album is too haunting and beautiful -- not to mention overtly rock-indebted in parts -- to be dressed down as binary code.

In fact, it's even hard to dress it up in wholly appropriate terms. Either because it's still relatively new or because it has been successful in skirting the language developed around rock 'n' roll, electronic music usually gets talked about in fleeting terms. Even staunch loyalists are reduced to using laughably ineffective words -- "bleeps," "bloops," "clicks," "cuts," etc. -- to discuss vastly different sounds with vastly different effects. Of course, this is part of electronic music's allure. But it's also what leaves critics trying to paint "Kid A" as an important record looking a bit like straw men walking into a barn full of hungry cows. Because their terminology is better developed, it's easy for naysayers to write off the album as overhyped drivel while supporters struggle to articulate the alien purposes of alien sounds.

That said, Radiohead have helped the cause by contrasting their electronic experiments with complements derived from the pop-song form, and vice-versa. On the album-opening "Everything in Its Right Place," Yorke sings, "Yesterday I woke up sucking a lemon," over a womblike field of imploding synth lines that sweeten his sour words. It's a supremely effective juxtaposition that tugs you by the ear just close enough to pucker along with his sentiment. Similarly, the mind-melting vocal manipulations on the title track drip over sizzling beats before ending with the ambient equivalent of a palette-cleansing sorbet served after an entree of shattered glass.

Flipping the template over, otherwise soothing songs get poked and probed with antagonistic gibes lifted from electronic music's soul-shunning elements. The wistful acoustic guitar chords that begin "How to Disappear Completely" roll over a seething drone that makes the melody anything but wistful. "The National Anthem," the closest thing to a rock song on the album, is excruciatingly compressed to the point of madness. The raw bass line barely varies, making its three notes sound like one and the same in spite of their differences. Even the song's free jazz-like ending is less a crescendo than a tightly wound taunt, hinting at much-needed outward release but instead collapsing in on itself.

From start to finish, it's like Radiohead are ripping out your brain with one hand and rubbing your thigh with the other. In this way, "Kid A" owes a huge debt to contemporary experimental electronicists like Oval, Aphex Twin, Authecre, Thomas Brinkmann, Vladislav Delay and scores of others. But while even the best electronicists stir up seductive sonic sparks, Radiohead have created something more like a backdraft in "Kid A." It throbs and pulses, hiding behind a closed door and sucking up all the oxygen in its vicinity. Open that door out of burning curiosity, and nature puts on a doozy of a show. But Radiohead see to it that you're just as content to watch the eerie spectacle play out by your feet, slowly breathing its lifeless breath.

Shares