The dinner was to be a celebration of five years of friendship, one that has survived good times and bad, including when my country bombed theirs for 11 weeks last year. Vladan Milenkovic, 32, my translator during the period of anti-government demonstrations in 1996-97, and his wife, Lidija, 31, had cushioned my stays in Belgrade, even sending me e-mails during the bombing last year when Vladan was called up to defend a Yugoslav military base and Lidija was left to care for their two children alone.

With all their troubles over the years, money worries and the seemingly endless looming threat of conflict, Lidija and Vladan always managed to make the best of things for themselves, their children and their friends. They long dreamed of the time Slobodan Milosevic would fall and Serbia would rejoin the world. Now it had finally happened.

So it was strange over dinner the other night to see them down. The pall in Belgrade has visibly lifted, people were smiling, Serbia was being welcomed into Europe and the world again. What could be wrong?

"You know, we have spent these past 13 years just trying to survive. And just realizing now all that we have lived through, it is so painful," Lidija said.

On Oct. 7 -- the day after Milosevic conceded his defeat to Vojislav Kostunica -- they had seen a documentary on Belgrade's Studio B. The documentary, "From Gazimestan to -," produced by Montenegrin television, chronicles in painful detail the 13 years of Milosevic's rule, from the 1987 nationalist rallies in Kosovo that bore him to power to archival footage of the war in Croatia, the destruction of Vukovar, the killing fields in Bosnia from 1992-95, the siege of Sarajevo, the massacre of Srebrenica, the constant exodus of refugees, the hyperinflation and growing poverty and isolation of Serbia itself to the war in Kosovo and NATO bombing of Serbia last year.

This footage would never have been aired on TV while Milosevic was in power. Now that he is gone, the full impact of his deeds is finally reaching the Serbian public.

"It was so painful to watch all that," Vladan said. "I was remembering the day I went to Lidija's law school and told her I have to leave for Malta," to avoid being drafted to fight in Croatia or Bosnia. "Realizing all that we have lost over the past years, I feel like a part of our lives was taken and we can never get them back. Ten years. I feel like we lost the best years of our lives."

Lidija and Vladan's response to the documentary is one mark of the difficult psychological process many here are finally undergoing. In the wake of Milosevic's removal from office, Serbia as a whole is facing the harsh realities of the crimes Milosevic committed in the country's name, crimes for which ordinary citizens paid with international economic sanctions and isolation.

Now that the years of hunkering down and steeling themselves to a grim present appear to be ending, how do Serbians reconcile with the awfulness of the past?

While there is a tendency now to blame Milosevic for all sins, people here are also aware of the strong support he rode to power on in the late 1980s and early '90s. They realize that Milosevic could not have survived in power for 13 years without the participation of hundreds of thousands of people.

Serbia's culture is in massive flux, and nowhere is that awkward change more pronounced than in the media. As the wrenching documentary aired by Studio B testifies, Serbia's arts and media are playing a new role in the process, exposing the Serbian public to information that, under Milosevic, many people already knew but only a small group of progressive people discussed.

Certain independent journalists, artists, actors, filmmakers, theater directors and cultural leaders battled the hate speech, lying and mass hysteria that overtook Serbia in the late 1980s. They resisted in the past few years as that propaganda morphed into a cruel, lynch-mob mentality against pro-democracy groups and opposition politicians here.

But many others from Serbia's professional media and arts world chose to participate in promoting Milosevic's program over the past decade, first for a Greater Serbia, and later in an increasingly vicious war of words between the Milosevic regime and its internal Serbian pro-democratic foes. Today, Serbia's arts and media world faces as much confusion and factionalization as the larger society it aims to reach.

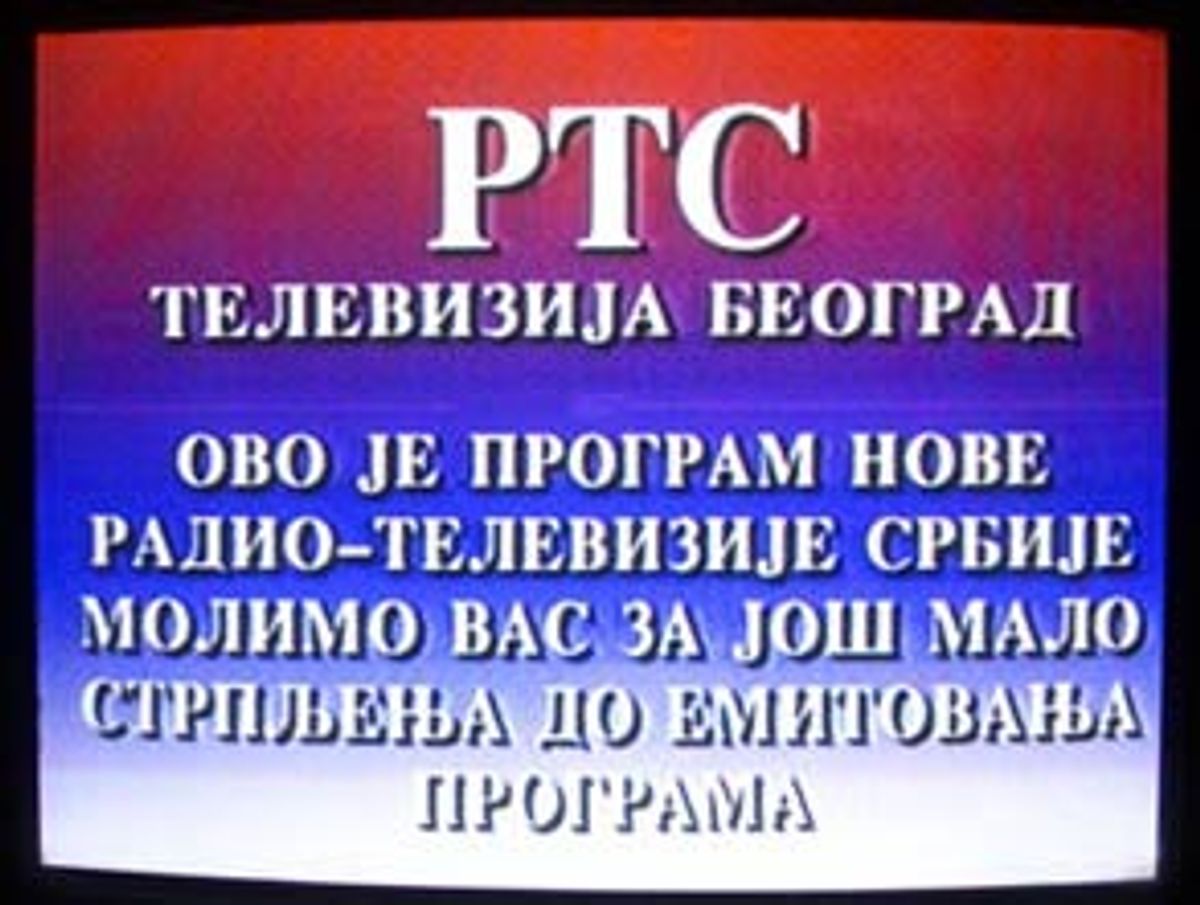

Radio Television Serbia (RTS), the bloated national broadcasting company with 6,000 employees, was the most far-reaching and destructive offender on behalf of Milosevic's propaganda front.

During the Bosnian war, when Sarajevans were under siege -- starving, without heat or water, shelled and sniped at by Bosnian Serb troops supplied and reinforced by Belgrade -- RTS broadcast reports showing a still photo from Sarajevo in the 1980s, untouched, in the sunlight. As if the war itself, and Belgrade's direct link with the shelling and siege of Sarajevo, were a complete fiction that could be willed away.

"During the siege of Sarajevo, it was shocking how in Belgrade, people here knew, but didn't want to know," says Gordana Susa. Once a prominent RTS journalist, Susa, now 52, quit when Milosevic came to power, and started an independent television production company called Video Independent News (VIN) in 1993. Its first act was to send reporters with cameras into besieged Sarajevo, a subject that got almost no coverage on state TV. Susa says, "That's the reason I started VIN. RTS didn't mention the Bosnian war at all until 1993," a full year after it started, and some two years after the war in Croatia started.

And when RTS did cover the wars in Croatia and Bosnia, it so distorted the facts on the ground as to make Serbs seem the main victims, denying their role in perpetrating atrocities.

During the Kosovo war last year, RTS never showed the 800,000 Kosovar Albanians expelled by Serb police and paramilitaries, except when a convoy of fleeing Kosovars was killed by NATO bombs. Yugoslav Information Minister Goran Matic even ranted on RTS last year that the hundreds of thousands of refugees pouring into Macedonia and Albania were actors, paid to walk in a circle.

Serbia now seeks an exit from this system of entrenched misinformation and denial -- but, for the moment, a remarkably soft one.

For now Serbian media, like most Serbian institutions, exist in a strange cohabitation with Milosevic's old guard. The federal parliament, the army, police, ministries -- all face the unresolved question of "who has to go."

The early momentum of Kostunica's victory suggested the heads of the army, police, RTS and other companies long in the hands of Milosevic would be quickly replaced, but that hasn't happened. Instead, close Milosevic Socialist Party colleagues and generals, even his feared secret police chief Rade Markovic, are now in consultations with Kostunica and his supporters over power sharing in the leadership of almost every ministry and institution.

Since that tense and joyous day when protesters seized the federal parliament and the RTS building and beat up its director, a strange, uneasy truce has prevailed inside major Serbian media between those who abandoned professional decency to throw their lot in with the old regime, and those who suffered under it.

After the regime fell, directors from the independent media were immediately appointed to temporary positions in charge of editorial departments of state media companies. But many of them have already dropped out, citing an overwhelming lack of support from the thousands of employees who supported Milosevic's work all those years.

The delay in firing the old guard inside the media is partly a concession to Kostunica's "softly, softly" approach to guiding Serbia safely out of the Milosevic era. The new leader has repeatedly promised to avoid revanchism and revenge against those who supported and benefited from Milosevic's system. During the revolutionary protests, that tactical move helped persuade those who feared Milosevic's fall from power to join the people's side.

On Monday, Kostunica achieved an important breakthrough, when the 18-member opposition party coalition that supports him (the Democratic Opposition of Serbia, or DOS) struck an agreement with other parties, including Milosevic's Socialists, on the formation of a temporary Serbian government that will serve until parliamentary elections Dec. 23.

But to a much larger degree, Kostunica, a constitutional lawyer with a reputation here for going by the legal books, has chosen to forge a government through consensus rather than decree.

Since it is the Serbian republic government that controls decisions about RTS personnel, the delay in forming an acting government has resulted in a delay in appointing new leadership to RTS. Thus many journalists who were purged from their jobs during the Milosevic era are still waiting to return. And those RTS journalists who stayed on in the Milosevic era by agreeing to propagate a version of events convenient to his regime are still there. It's more than a bit disconcerting.

For viewers, this produces an odd effect: The very same faces of RTS newsreaders who for years spouted Milosevic's rhetoric against opposition "traitors" now laud each move made by opposition president Kostunica.

Radio B92, a cutting-edge independent broadcasting company here, aired a program Friday morning on journalistic responsibility in which one RTS newsreader said she is not guilty for the statements she read in the past, because she didn't create the reports, she only read what she was given.

Some prominent independent media leaders believe the period of accommodating the old guard is temporary. "Those journalists who are guilty of promoting hate speech, for inciting hate against other nationalities and calling for lynching, those who wore [military] uniforms during the wars while shooting film, they will face criminal charges," vows VIN editor Gordana Susa.

As journalists are confronted with the issue of responsibility for what happened under Milosevic, they will also have to learn a new skill: critical thinking. Without it, many do not know how to report rather than spread propaganda. In fact, Susa and others say, state television has done little more than switch loyalties from Milosevic to Kostunica.

Susa was among those well-known independent journalists in Serbia who, immediately following Milosevic's downfall, were asked to head the discredited state news agencies until new directors and editors can be appointed. Assigned to head the information/editorial desk at RTS, Susa was so disgusted, she said, with the lack of change of personnel and the complete lack of critical thinking she found among RTS staff that she left last week.

"I would watch the RTS journalists, trying to compare news from [independent news agencies] Beta and Fonet and Reuters, and they would suddenly feel confused and tired, they didn't know what the news was," Susa described. "This is the hardest job, to teach people how to think. And we just don't have enough educated, professional people at RTS. We have to educate people to listen to multiple opinions, to create a forum for dialogue."

For more than a decade, the semi-dictatorship discouraged its citizens from thinking for themselves -- that, Susa says, is the major problem. "Seventy-five percent of the Serbian population is basically illiterate. That is basically why state TV is so powerful here," Susa adds.

"You must understand 13 years of repression. Can you imagine, the newsreaders at RTS used to prepare the news by reading Tanjug [the Milosevic-controlled state wire agency] wires directly? Without any comment? They only changed any word if they could find a better word with which to spit at the opposition."

"This is really the biggest problem," echoes Sasa Mirkovic, the young director of Radio B92. "Everyone who was so obedient to Milosevic, now is so obedient to DOS. And as I can see, DOS isn't complaining too much about that."

While Mirkovic's B92 and Susa's VIN, with their combined staff of fewer than 200 people, can't have the reach of RTS, with its staff of 6,000, the independent groups are steeped in what RTS sorely lacks: journalists who know how to handle a diversity of opinions and ideas.

Mirkovic makes clear that, like Susa, he is disgusted with what he's witnessed at RTS, which he describes as a simple editorial transfer of allegiance from Milosevic to the new DOS leadership. And as far as Mirkovic is concerned, he has no desire to take over RTS and try to reform it.

"They [RTS] dug their bed, and they can dig themselves out of it," he said. At B92, "We are with the people, between the opposition and the regime. No authority can be misused. We need to have balance, even in our coverage of the new leadership."

Mirkovic says the station has an important role to play in teaching this society how a democracy should function. "We want to create a TV campaign to remind people that the government exists, and is responsible, to them, the people," Mirkovic says.

Mirkovic spoke to me at a sports cafe down the street from B92's offices in the House of Youth building downtown. Last year during the NATO bombing, Milosevic's police seized the offices, equipment, frequency and name, trying to use the station's youthful image and popularity for Milosevic's propaganda. Mirkovic didn't dare go back to those offices until they were officially restored to the station.

The real B92 was forced to use the name "Free B2-92," and to broadcast on the Internet and satellite TV -- which few Serbs have access to. Its new office addresses were kept secret out of fear of more police raids.

A few days after our interview, opposition leader and new Belgrade mayor Milan St. Protic gave B92 its name and offices back. Mirkovic and his young staff of 150 joyfully moved back into the House of Youth building, down Makedonska Street from state RTS, and the newspaper Politika.

B92 and its parent organization, the Association of Independent Electronic Media (ANEM in Serbian, with some 50 independent TV and radio stations around Serbia as members), have also begun experimental television programming on a frequency provided by the central Belgrade municipality of Vracar. B92/ANEM debuted on Belgrade television last week with a Western-made, Serbo-Croatian-subtitled documentary on war crimes in Croatia, and has followed up with several more war-time documentaries that offer Serbian viewers some of their first television pictures of the wars they experienced indirectly.

B92, ANEM and VIN have long been covering taboo subjects such as war crimes. Now these companies and programs have unimpeded access to the Serbian airwaves. Already, that access is affecting public discourse by articulating subjects, ideas and recent history many people here are aware of, but have not had a forum to discuss until now.

Janko Balat, a documentary filmmaker who has produced three films for ANEM, has dedicated his next film to asking the question, how did Serbia come to suffer Milosevic?

"The most interesting thing for all of us to reexamine is our own guilt for things here," Balat said last week in an interview near Belgrade University's humanities faculty. "Only through portraits of ordinary people, to see what causes an individual to step by step make compromises, in their work, in their families, in their own morals, to accept this life under Milosevic the past 10, 12 years, can we understand what happened here."

Slight, in a light denim jacket, Balat blends in with the students and young people drinking coffee and chatting at the other tables and strolling nearby through downtown's main pedestrian thoroughfare. But his documentaries capture searing insights and themes that crystallize the traumatic upheaval this society has experienced over the past decade.

Balat's 1994 documentary, "The Crime That Changed Serbia," profiles the mafia underworld that exploded in Serbia that year as a result of international sanctions, Belgrade's wartime spending and hyperinflation. Three of the underworld figures Balat profiled in the documentary, Bojan Banovic, Goran Vukovic and Mihail Divac, were killed before the film finished production. Six years later, only two of the dozen men profiled are still alive.

His second documentary, "Ethnic Cleansing," looks at the war-crimes trial of a Yugoslav accused of atrocities in neighboring Croatia. His latest, "The Anatomy of Pain," released last spring, delves into the night 16 RTS employees were killed when NATO bombed the RTS building April 22, 1999. Soon after the bombing it emerged that the director of RTS, Dragan Milanovic, had ordered his staff to work their shift or lose their jobs, even though he knew it was going to be bombed, and had informed a personal friend of his to stay away that night. The film is as critical of the RTS and Serbian leadership as of NATO.

The film, Balat said, recounts a moment "when human life was very cheap, and especially cheap in the building of state TV, during the NATO bombing. The regime tried to use that loss of life for its propaganda purposes. But that was the breaking moment for the public," when people began to understand that the state propaganda was absolutely cynical.

After that, he said, RTS propaganda had a strange reverse effect. "Every time they showed a picture of" Milosevic's wife, Mira Markovic, who headed her own corrupt left-wing political party, "it was as if they had run five advertisements for the opposition." In a sign of how much things have changed here, Balat's "The Anatomy of Pain" aired on RTS last week.

Balat's next documentary probes the question of individual responsibility for what happened in Serbia through portraits of real people.

"I think for Serbia to have some better future, this question is essential," Balat said. "How did we end up with such an authoritarian system? How did we as individuals allow this to happen? I think I will dedicate the next part of my future to exploring this question."

The question about responsibility, and many people's fear of addressing that question, is at the heart of Serbia's fragile transition from the Milosevic era.

But so far, there is no consensus on just what Serbia is responsible for. There is the question of who is responsible for supporting Milosevic's disastrous rule. And there is another, deeper moral question, that people here are not yet articulating: How responsible are people -- as individuals, and as a nation -- for the crimes Milosevic committed in their name?

For now, Serbia's media is approaching these questions obliquely. Acting director of Studio B Marko Jankovic told me he deliberately altered the actual title of his documentary from "From Gazimestan to the Hague" to just "From Gazimestan to -." The elimination of "the Hague" in the title -- and the war crimes issue it connotes -- is telling.

Kostunica has repeatedly said that the question of Milosevic's guilt is one Serbs should decide, not an international war crimes tribunal. The subtext of what Kostunica is saying is that Serbs, if they choose, should try Milosevic for crimes he committed against Serbs, and that Milosevic -- and, by extension, Serbia itself -- should not be put on trial for crimes its troops, paramilitaries and police committed against others, including the slaughter of 8,000 at Srebrenica, the worst massacre in Europe since the Holocaust.

But that position may be changing. In an interview for the CBS news program "60 Minutes II" that aired last Tuesday, Kostunica is reported to have admitted for the first time that Yugoslav Army troops and Serbian police killed Kosovar Albanians.

"I am ready to ... accept the guilt for all those people who have been killed," Kostunica said. "For what Milosevic had done, and as a Serb, I will take responsibility for many of these, these crimes." Asked whether Milosevic would ever face trial, Kostunica said, "Somewhere, yes."

But almost as soon as the interview aired, Kostunica's office issued a complaint to CBS, saying those sentences had been taken out of context, and downplaying Kostunica's owning up to Belgrade's role in atrocities.

Like their new leader, Serbs are wrestling in a new public forum with questions about Serbia's role in the world, its governance and its war-time responsibility, as the nation tries to shape a future without Milosevic.

Shares