Early in his career, when Harold Ramis performed in films that he co-wrote, such as the smash-hit Bill Murray vehicles “Stripes” (1981) and “Ghostbusters” (1984), he registered as an amiable blur with specs on. Side by side on-screen with genius improviser Murray, he seemed amused and reticent, even smug. As an actor he didn’t have impact. Maybe he was turning himself into a human antenna to catch Murray’s weirdest wavelengths and audiences weren’t used to seeing such an oddly bent straight man.

Or maybe he was smug. It could be that he found his creative identity only as he defined himself, increasingly not as an actor-writer but as a writer-director. When he reached maturity as a filmmaker with “Groundhog Day” (1993), he had the wit to strip his old pal Murray of that late-night-TV trademark — ironic self-satisfaction — and get audiences to love it.

Indeed, from “Groundhog Day” on, Ramis the director has been the soul of anti-smug. “Groundhog Day” tried to bid farewell to Reagan-Bush-era careerism when slick weatherman Murray chilled out and found the better angels of his nature in a small, wintry Pennsylvania town. As the ’90s became even more frantic, “Multiplicity” (1996) had Michael Keaton discovering that cloning could not help a contemporary man have it all. Even “Analyze This” (1999), which premiered at the same time as “The Sopranos,” forced Robert De Niro to acknowledge that all a don’s judges and all a don’s men couldn’t put a godfather back together again, at least when it came to combating anxiety.

Yet Ramis hasn’t lost the inspired scampishness that helped make mere catchphrases in his youthful scripts — like “That’s the fact, Jack!” from “Stripes” — explode like dynamite punch lines. And his appetite for all-out physical comedy hasn’t diminished since his 1980 directorial debut with the baggy-pants golf comedy “Caddyshack.” What Ramis tries to do is find premises he believes in and then erect platforms for skilled, slap-happy performers.

He does it again in “Bedazzled.” This brashly entertaining movie opened to bizarrely mixed reviews and fair business two weeks ago. A remake of the 1967 Dudley Moore and Peter Cook cult classic of the same name, it stars Brendan Fraser in the Moore role of a lovelorn shlub and Elizabeth Hurley in the Cook role of the devil. It’s a rowdy kind of farce anthology in which Hurley offers Fraser seven wishes in exchange for his soul. Fraser tries on fantasy identities from a Neanderthal basketball star to an ultrasensitive soul who tears up at a sunset. Hurley’s many guises include those of a supersvelte meter maid and a brusque, seductive schoolteacher. The combination of bull’s-eye casting and erotic pranks brings on belly laughs all the way through.

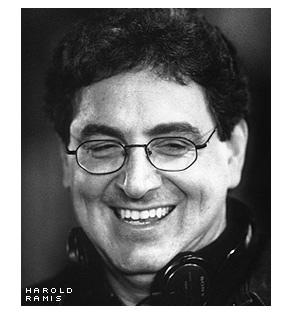

I spoke to Ramis by phone at his home base in Chicago. He discussed where he finds the sparks to set off his comic conflagrations.

In the original “Bedazzled,” some of the scenes between Dudley Moore and his love object, Eleanor Bron, were like the satiric dating routines that Mike Nichols and Elaine May developed in their Chicago days. Having a graduate of Chicago’s Second City troupe do this remake of “Bedazzled” makes it feel like the material’s come full circle.

Absolutely. What you identify as some continuity or relationship between Nichols and May and the “Beyond the Fringe” group — it’s a real connection. These groups were in touch with each other. Peter Cook and Dudley Moore were in a college improv group, the Establishment, and they did an exchange with Second City: They came to Chicago and Second City went to London. These are common streams; that’s probably why I so wholeheartedly embraced that kind of comedy.

I love the original movie. There are certain ideas that have mythic importance in our culture. They’re dealt with all the time and they keep coming around and around. And here’s one that hasn’t been dealt with comedically for a while: the fable of Faust, of selling your soul to the devil so your dreams come true. This “Bedazzled” is partly a homage to the original film. But I didn’t merely want to copy that movie. You can’t duplicate its casting, which had a specific quality — English, and of its time. I wanted to do a contemporary, energetic, broad, colorful, American spin on this.

The original “Beyond the Fringe” depended heavily on the rapport of Cook and Moore.

That’s one reason Elizabeth Hurley plays the devil; I was wracking my brain for a team like that, and if it didn’t exist, how could I create it? That’s when my wife said, “Why not a woman for the devil?” It made sense from every social, cultural and entertainment point of view.

You don’t toy with the Seven Deadly Sins the way Cook and Moore did in the original film, most effectively when they had Raquel Welch play Lust, although, actually, the Seven Deadly Sins went in and out of the old movie, and weren’t treated systematically.

That’s why it felt theatrical to me in the original film — the Sins kind of took you out of it. Creating more of the devil’s world, oddly enough, made it less convincing. But Cook’s choice was great and so appropriate to him as a character: creating a devil who was tired of being the devil and couldn’t wait to get back to heaven. We had a whole different theological spin that liberated us from that view. Our film is really grounded in postmodern existential reality, if you’ll forgive me for that.

I’ll forgive you for that, but first you have to explain it to me.

You know: The old theological models posit good and evil as things that are providential, God given. Temptation and redemption come from outside us, somehow; the devil is an agent on Earth. But I totally believe that good and evil are the result of personal choice. We should take responsibility for what we do and not lay it off on some objectified demonic evil in the world.

It sounds as if you were always aiming for the wholesome happy ending that some folks have grumbled about.

At the risk of being a moralist, we always knew superficially what the movie was about, but I need to work from meaning. Even the broadest stuff is grounded in meaning for me. It has to make some sense morally, philosophically, psychologically and spiritually. So when I was trying to think what is the raison d’être for this particular project I’ll spend two years on — what’s going to keep it from being some jerk-off exercise to make a few bucks for everybody — I started to consider all these questions.

A lot was being written then about Columbine, and the pressure on teenagers, and this tremendous alienation they all felt. Everyone feels like a loser, everyone feels ugly, no one feels good enough, and that’s why kids torture each other. I thought about it in terms of our consumer culture and images that come from advertising. There’s this constant feeling that comes along with it of never being good enough — my hair isn’t good enough, I don’t have good abs, I’m driving the wrong car, I don’t have enough money.

In this movie it kind of devolves down to: What do chicks go for? [Laughter] I guess that’s the simple Freudian nub of it. What will win me love and affection? So the project suddenly made sense to me: Take this guy who’s a complete geek and have him explore all the things we’re told will make us worthy in this society, and have him find out that’s not where self-esteem comes from. Then I wanted to pose the devil, and the angel who shows up near the end, as Brendan’s spirit guides. I wanted to remind people that the devil, too, is an angel. By pulling in opposite directions these two help our hero find the path.

You start out with these serious thoughts, but then you erect this no-holds-barred comedy on top of it — unlike other ambitious comedy makers, who put their humor in deep freeze whenever they start to get serious.

I believe you can always make jokes; I’ve worked with extremely funny people. You can sit around in a room eight hours with these people and something funny will be said or will happen every 30 seconds like clockwork. And they can be funny with anything. Christopher Guest can do 10 minutes on a fork! Just anything. It’s not that laughs are easy to come by. And they’re not the hard part — it’s deciding what idea you’re serving. Once you have the idea, then the fun starts. Then I sit around with [writers] Larry Gelbart and Peter Tolan and we start wondering, “If you stop 100 people on the street, what would their top seven wishes be?”

When you did your group search for Brendan’s seven wishes — how did they intersect with what you wanted?

With what I wanted? I’m as much a product of our culture as the audience. People love asking, “How do you know what’s going to be funny for the audience?” and I insist you can’t predict that. You have to hope that what’s funny for you also jibes with the audience’s taste. I just went from the things I always wanted to be.

One wish did get cut and replaced. I always thought that if I had seven wishes I would really want to explore my dark side — get out there. We shot a wish with Brendan almost as a “Sid & Nancy” parody, with Brendan as the most disgusting British rock star you’ve ever seen. It’s going to be on the DVD. When we tested it, people were appalled. It wasn’t just that they said, “Oh, it’s not funny.” It’s like they were offended.

Do you find previews useful for the final cutting of a movie?

They are market-research previews, but from my point of view it’s not the market I’m interested in. I’m interested in real people — where they’re laughing, when, how long and how loud. Where do they seem bored? Where are they coughing? Where are they getting up to go to the bathroom? Knowing that helps the general tuning of the film. And secondarily, there are the four quadrants: Which quadrants respond best to the film? Young males, young females, older males, older females? So while the studio is targeting the right quadrants for its advertising, we’re tuning up the film.

Given your concept of the movie, the casting is crucial. And I think Hurley is great. She has this italicized quality.

Italicized quality — I like that. I relate her part to De Niro’s part in “Analyze This”: Both parts read really well. You knew that every actress who fancied herself slightly wicked or sexy would want to do it. And that was the case. We got tremendous response from the agents when we put it out there. You start with preliminary casting lists of the performers who could play the major roles. Elizabeth was definitely on everyone’s list. But probably the one film I had seen that gave her substantial screen time was the first “Austin Powers” movie. In a way we were taking a chance. But she was the second person we met, and she was great in the meeting. She is so charming and witty and comfortable with her sexuality — and so grounded and professional, having been a producer. She understood the part and was eager to do it. She also is sophisticated, worldly. The British accent certainly helps: It seems to most Americans to reek of sophistication and wickedness. [Laughter] And Elizabeth has the public reputation to go with it! She’s a naughty girl in people’s minds. I don’t know that she is really. But that’s the image she cultivates and it certainly works for the movie.

It must have been a kick to do her wardrobe — Hurley brings down the house when she shows up in a tight, short tartan skirt in the schoolroom. She’s more like a fantasy schoolgirl than a schoolmarm.

It was like creating our own Frederick’s of Hollywood catalog! And Elizabeth embraced that totally — being a naughty nurse and a cheerleader and, in the scene that will be on the DVD, a naughty French maid. She got to camp it up in a way. And when it came to the high-fashion clothing she wears in the movie, she worked with Deena Arpel, our designer, and made calls to friends at Versace and so on, and stuff kept pouring in.

Brendan Fraser is so underrated as a comic actor.

On the studio’s male comedy list there are some real big hitters in box-office terms. Comedy is king in a way, and there are certain $20 million players whom studios want to get in any comedy. In the context of Will Smith, Adam Sandler, Mike Myers, Eddie Murphy and Robin Williams, Brendan could get overlooked. When you think “comedy,” your first instinct is not to put Brendan up at the top of that list. But I looked at his body of work and the tremendous variety of it and his sincerity and vulnerability and technical ability. I have little kids, so I saw “George of the Jungle,” believe me, more than once, many times. And I thought, “What a nutty heroic performance this is.” Then I saw “The Mummy,” where he was thoroughly convincing and charismatic in an “Indiana Jones” role. I thought, “Gee, this guy is great.” Meeting him just cinched it. He is a completely wonderful person on every level.

It’s hard for an actor to deliver something authentic when up against special effects.

He is so game, and he is so dedicated. Belief is very important for him, too; even his less successful films are grounded in some meaning or message. He’s very much about the quality of his work. And doing these different makeups and prosthetics — for every one of those characters he was in the chair a minimum of three hours. Even the writer character he plays has an extra nose tip, a more refined nose than Brendan’s real nose. It looks surprisingly like the nose on Frances O’Connor [who plays Fraser’s romantic ideal]; when they stood together in that scene I thought they were a great couple.

In “Groundhog Day” you depicted a guy who needed to relive one day numerous times to find himself. In “Multiplicity” the hero had to experiment with cloning before he could set healthy priorities for his life. Here you have someone who tries on alternate identities. Are you consciously exploring the fractured nature of the way we live today?

Of course I’m conscious of it, but I might have said as much as I want to say about it now, in the films. “Groundhog Day” came to me as an original script from Danny Rubin, but the core of the movie was always there. It was the Nietzschean/Buddhist premise of eternal repetition and what we could learn from it. And the response from the spiritual community to that movie was unbelievable. I literally got letters from every known religious organization and discipline, from yogis, Hasidic Jews, Jesuits, psychoanalysts — all claiming the movie, all saying you must be one of us because this movie so perfectly expresses our philosophy. That one for me was about getting off the wheel of comedy by losing yourself, which is a purely Buddhist idea: The hero stops thinking about himself and starts performing service. That’s what Mahayana Buddhism is all about.

And “Groundhog Day” hooked into a more general idea that people really respond to: What if you could do things over again? Danny Rubin actually took Elisabeth Kubler-Ross as a model — her five stages of death and dying — and we used that as a template for Bill Murray’s progress.

Then “Multiplicity” came to me as an original from Chris Miller and his wife; I had worked on the “Animal House” script with Chris. To me, that one was about the divided self. I had been doing a lot with the ritual men’s movement — the Robert Bly stuff. A lot of Jungian archetypes were floating around in my head. Chris’ original story was much more about the social dilemma of being too busy in the world and needing to split ourselves because we have too many conflicting desires and responsibilities. I thought that was a great start. But from a psychological point of view I began to wonder why we are so divided about what we want to do in life. I broke it down into: We men have a deep masculine self, and we have an inner feminine self, and we have an inner child, and they all demand attention in a certain way and all have conflicting wants and activities. Being a working father with a career and my own desires — I’m bringing up the rear, a distant third. That’s just what it is. It seemed like a great contemporary dilemma to examine in comic terms.

Manohla Dargis [of the L.A. Weekly], after “Groundhog Day,” “Stuart Saves His Family” and “Multiplicity,” said they were all films about the problem of being a good man in the ’90s. That made sense to me.

On the recent “Frontline” show about Bush and Gore, a friend of Bush’s said their college life was just like “National Lampoon’s Animal House.” As one of that film’s writers, how do you feel about that statement?

I’m sure it’s accurate; it just proves our point. We were celebrating what most people go through when they go to college — this energizing dose of liberty and license.

But I’m pretty sure Bush himself wouldn’t say that today.

Well, he wouldn’t. Part of the point of the movie was that young people in college are inherently countercultural — and are supposed to be.