It's 5 p.m. and the swatch of sidewalk outside Hillary Rodham Clinton's Seventh Avenue headquarters is overflowing with human traffic. Blocking its path are a set of police barricades, behind which stand 50 or so protesters with megaphones and cardboard signs that read "Vote for the mensch, not the wench" and "Hillary + Hamas," perhaps a successful result of attempts by the New York Republican Party to link Clinton to the Palestinian terrorist organization.

"Get on your broomstick and go home," screeches a voice over the loudspeaker, crackling from excitement and overuse, its followers cheering on.

The protest serves as a reminder that, lest anyone forget, no name attracts more right-wing wrath than the name of Clinton.

It is this hatred that Hillary Clinton seems to feed on. On the stump, her opponents' hatred of her is the chief issue of her campaign. Lazio and the Republicans attack her, she says, while offering no plans or vision for the future of the state or the country. Candidate Clinton -- much like another Clinton before her -- seems to use that hatred as a source of strength, in a masterful move of political judo.

"I don't take any of this personally," Clinton says, speaking to a small group of mostly Jewish voters in the Bronx neighborhood of Riverdale Monday night. It's the Hillary Clinton who people learned to cheer only after scandal broke, the one who kept a stiff upper lip. The woman who, Tammy Wynette swipes in 1992 notwithstanding, overcame ruthless public embarrassment to stand by her man -- and stand up to congressional Republicans who hounded the Clintons. Her public approval ratings peaked when impeachment was at its apex. An August 1998 ABC News poll showed Clinton with a 71 percent national approval rating, a dramatic jump from a January '96 CNN poll that had her approval at only 49 percent.

It's that woman she's trying to sell to New Yorkers, and part of her strategy to preserve this winning air of righteousness has been to regularly invoke the names of her husband's chief adversaries. At this event, she brings up House Majority Leader Tom DeLay, R-Texas -- impeachment impresario and perpetual thorn in the president's side -- when she describes how both were honored by a group for their involvement with foster-care reform.

"It was probably very painful for him to stand up and talk about how we worked together," she laughs, before stiffening that upper lip. "But I understand that what they say for public consumption is for political purposes." It's these same "political purposes," after all, that she tries as often as possible to link to her opponent, Rep. Rick Lazio. ("He was part of the Gingrich Republican leadership that voted to shut the government down, that voted for large tax cuts and large spending cuts that would have devastated education and healthcare," she tells a group of students at Fordham University.)

Lazio's chief attack strategy is also to invoke the past -- namely, Clinton's husband, even raising the Monica Lewinsky scandal as an issue in their first debate. She has tried to deflect this by criticizing not only Lazio but an ominous-sounding "they" -- presumably the same "they" behind the "vast right-wing conspiracy."

That's fairly appropriate, since this race will be viewed largely as a referendum on Hillary. Lazio is almost an afterthought: Both candidates have worked to make this a choice between the good Hillary and the bad Hillary.

And right now, voters seem increasingly uncertain which it is. Vice President Al Gore runs comfortably ahead of Gov. George W. Bush in presidential polls here, but Clinton maintains just a narrow lead in most statewide polls. A recent Quinnipiac College poll shows her lead shrinking to three points, 47-44 down from a 50-43 lead earlier in the month, and well within the margin of error.

That makes every minute remaining in the campaign vital. And it just keeps getting uglier.

For someone not used to seeing her campaign, there is something almost surreal about watching Hillary Clinton work a room. On Monday in Riverdale, the room is small, the curtains heavy and drawn shut, and it is an uncomfortably hot 80 degrees as people pick through plates of poached salmon. There is no particular buzz in the air, no driving energy. The first lady drones on, regurgitating her canned stump speech, visibly run-down after a long day on the campaign trail. It is astonishingly ordinary.

When Clinton announced her candidacy, it was easy to imagine the race being anything but ordinary. Reporters delighted in the potential slugfest between Clinton and New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani. But when Giuliani withdrew from the race in May after being diagnosed with prostate cancer, Republicans quickly rallied behind Lazio, who was largely unknown to New York voters.

Quickly, Clinton pulled ahead, and has remained the front-runner for most of this race. With New York a lock for Gore, and Clinton running comfortably ahead of Lazio, it seemed almost a given that the first lady would make her way to Washington as a U.S. senator.

But the race continues to be hard fought. Over the weekend, Republicans first tried to link Clinton to the terrorist attack on the USS Cole in Yemen and to controversial donations from Arab groups. This, the Republicans said, was more reason to question Clinton's loyalty to Israel. (Clinton has come under fire for voicing support for a Palestinian state, and for her now infamous embrace of Yasser Arafat's wife, Suha.)

Tellingly, the poll numbers that show the race tightening also show that Lazio's numbers have not moved. The tightening of the race has been because Clinton's numbers have dropped.

Those numbers have buoyed the spirits of the Lazio campaign. They point to the fact that the Senate race remains close, even as the Democratic presidential nominee holds on to a double-digit lead in the state.

"New York has a history of ticket splitting," says Lazio spokesman Dan McLagan. "For at least the last decade, every time there's been a presidential and statewide race together, New Yorkers have gone one way at the top of the ticket and the other way at the bottom of the ticket."

In 1992, Clinton carried New York as Republican Sen. Al D'Amato was reelected. Two years later, New Yorkers sent Democrat Daniel Patrick Moynihan back to the Senate while electing Republican George Pataki over incumbent Democratic Gov. Mario Cuomo. In 1998, Pataki was reelected while D'Amato was defeated by Democrat Charles Schumer.

"I think you're seeing a lot of moderate Democrats, Reagan Democrats, really people who are fiscally conservative and socially moderate that will gravitate toward Congressman Lazio," McLagan says.

Of course, comparing the Senate race to the presidential race here is a bit disingenuous. The two Senate candidates have spent millions of dollars on this race, while presidential expenditures in the state have been negligible. In that sense, New York is a sort of photographic negative of California, where the presidential race appears to be tight, while Sen. Dianne Feinstein maintains a double-digit lead over her Republican challenger, Rep. Tom Campbell.

McLagan also points to numbers in the poll that show Lazio doing relatively well among the state's Jewish voters -- no doubt a reason for the state GOP's attacks on Clinton's commitment to Israel. "That's a dangerous sign for the Clinton campaign," he says.

Down the home stretch, Lazio has zeroed in on Jewish voters, who are generally Democratic, as potential ticket-splitting swing voters. Calls about the USS Cole bombing that went out over the weekend were targeted at Jews, as is a new spot featuring Giuliani testifying to Lazio's commitment to Israel.

Lazio also has been critical of Clinton's acceptance of $50,000 from the American Muslim Alliance and $1,000 from Abdurrahaman Alamoudi, former executive director of the more radical American Muslim Council. Lazio accuses both groups of supporting terrorist attacks like the one against the USS Cole. Under fire, Clinton returned the money, even though privately her advisors say Lazio is promoting anti-Arab sentiment; while Alamoudi has publicly pledged his support for Hamas and Hezbollah, the American Muslim Alliance in Washington is considered a mainstream Arab political group.

But Lazio remains unrepentant. "There's one candidate here who's actually receiving financial contributions from a group that supports terrorism, murder and violence to achieve political gain," he said on Tuesday's "Today" show.

The New York papers have criticized Lazio's line of attack. Even Newsday, in its endorsement of Lazio, wrote, "Politicizing a national tragedy and tarring Arab-Americans with so broad a brush is reprehensible."

Still, the barrage of mudslinging has Democrats worried about turnout, a factor which many here believe may ultimately decide the election. So while Gore has been hesitant to ask President Clinton to campaign on his behalf, the president came to Harlem Tuesday night to energize core Democratic supporters, speaking to about 400 African-American leaders and clergy at the Kelley Temple Pentecostal church in Harlem.

"Brothers and sisters I want you to know, we be the base," says state Comptroller Carl McCall, the state's highest-ranking African-American elected official, and potential candidate for governor in 2002. "They may not want to say it, but they're talking about us, and the fact that we will determine the outcome of this election."

"The president of the United States is in the 'hood," says Bishop James Gaylord.

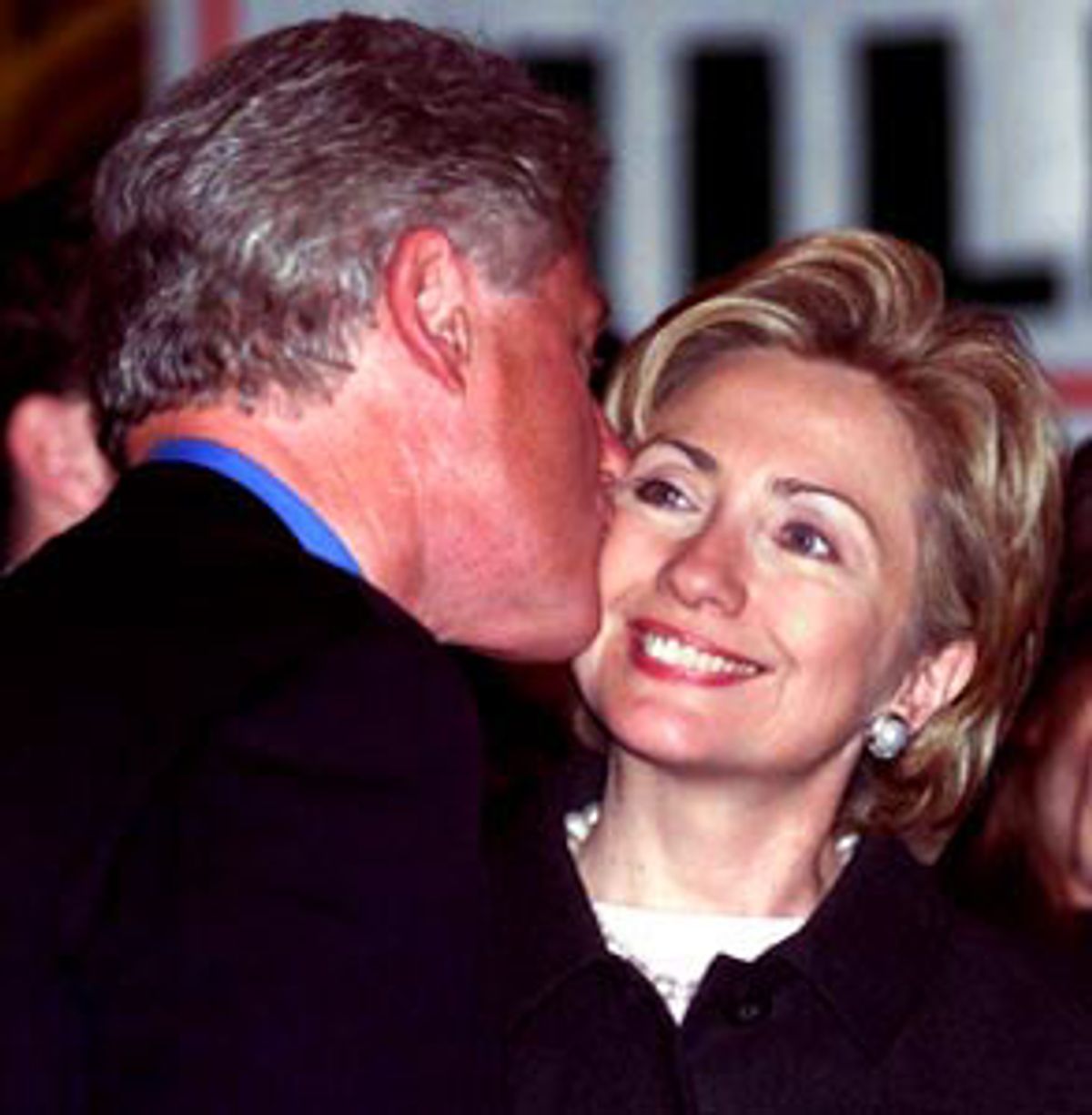

By the time he takes the podium, it's clear that Bill Clinton is home. Using the cadence of a preacher, the president riles up the crowd, peppering his speech with rhetorical questions: "Isn't that right?" (The choruses respond: "That's right.") Saying African-Americans will make the difference in the election, Clinton makes an impassioned plea for his wife's election.

"The most important person in the world to me is running for senator," Clinton says. "I've never known anybody that cared more, knew more and worked harder, and had a better ability of blending heart and mind and passion and commitment than Hillary. She will make you very proud."

Hillary Clinton, meanwhile, spent much of the early part of the week trying to shore up the Jewish vote. At the East Midwood Jewish Center in Brooklyn, a man introduced only as "Lev" was working the crowd, banging through a synthesizer-driven power pop version of "Hava Nagila." About 200 seniors sat clapping along, pounding rhythmically on tables, waiting for the first lady to arrive.

And after being introduced by former New York Mayor Ed Koch, Clinton unleashed her harshest attacks on Lazio to date. After a sedate performance earlier in the day, an energized Clinton took the stage, eyes bulging, her hands constantly in motion. "This campaign should be about issues, not me or my opponent," she said. "And certainly not about his misleading, inaccurate, offensive, outrageous, despicable attacks. It ought to be about you and your families ... He doesn't want us to know where he stands, what he's done and what he will do. Well, you can run a negative campaign, Mr. Lazio, but you cannot hide. You cannot hide from your record, you cannot hide from your positions." Then she pulls in the bogeymen. "You cannot hide from the fact that you would go to Washington and be a vote for Trent Lott and Jesse Helms. You cannot hide from the fact that you do not represent the mainstream of New York voters."

When asked later if the stepped-up attacks on Lazio were a response to the tightening of the race, she replies, "We're in the last week of a hard-fought election. There are clear differences and it's time to ratchet up the energy." But the energy on the other side remains high, driven by a visceral dislike of the first lady. If she wins -- and, say, Gore loses -- the sky will suddenly seem the limit. Should she lose ... it's back to being Bill Clinton's wife.

Meanwhile, Lev is back on the synthesizer, crooning as Hillary performs the grip-and-grin. "I'll make a brand new start of it, in old New York. If I can make it there ..."

Shares