Four hundred black-clad San Franciscans are marching to City Hall on a sunny Saturday afternoon. They're mourning the death of the arts and demanding that government punish the Internet economy that killed it. Never mind that a good number of them work for these murderous dot-coms (the term now used across the United States to deride all forms of high-tech business). Or that the Internet does have its good points, especially e-mail, which is how most of them learned about the mock funeral procession. It's just not enough, they argue. The benefits do not outweigh the costs. The Internet has brought sky-high rents, gentrification, thousands of evictions and sent the price of sushi through the roof. The message of the protest is clear: We'd all be better off without it.

"[The Internet] hasn't made the world a better place," says Debra Walker, an organizer of the day's event. "It's just a vehicle for capitalization, a pyramid scheme. A few people have made a lot of money and the rest of us haven't and won't."

Given a choice, says Susan Lofthouse, 36, a theater technician who has lived in San Francisco since 1985, "I'd choose the arts over the new economy. I liked things the way they were."

She's hardly alone. The Internet, once the darling of Northern California, is now an almost malign presence. Few people recall how the Internet boom helped pull California, and possibly the world, out of a disastrous recession. The new economy is no longer a savior. Instead, as one protesting musician put it, it's "a bad, bad boy that needs to be punished."

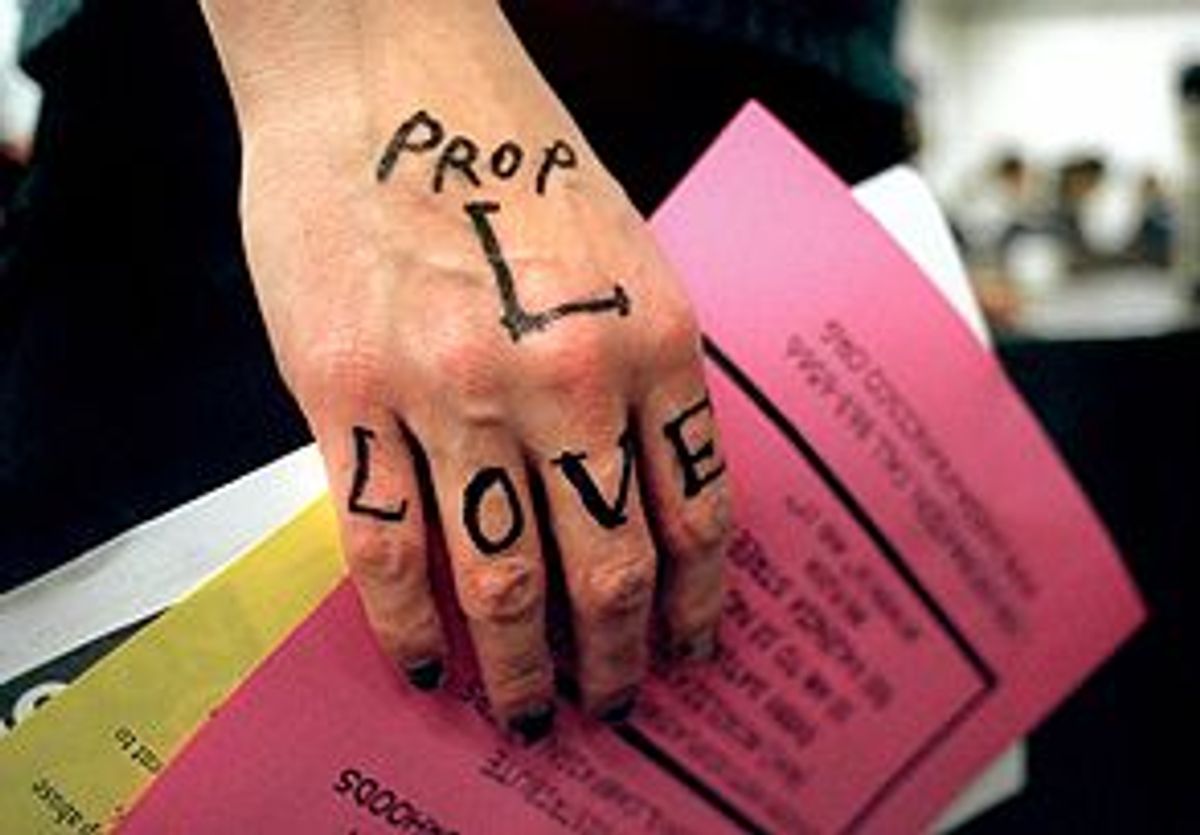

San Francisco represents the physical heart of the anti-dot-com movement -- on Tuesday, the city's voters will decide whether or not to approve "Proposition L," one of the most extreme anti-growth ballot initiatives in San Francisco history, but the debate over the worth of the Internet is now a national phenomenon. Full page ads attacking the Internet and the high-tech economy appear regularly in the New York Times. Dot-com excesses have become a national symbol for ludicrously out-of-control capitalism.

Gentrification fears fuel the fervor. There are 33 development-related questions on ballots in 17 states, according to the Sprawl Watch Clearinghouse in Washington, which tracks land-use policies. Capturing the collective mood perfectly, an Oct. 23 San Francisco Chronicle story reported that cities in once-friendly Silicon Valley were "closing ranks in a simmering battle against dot-coms that swarmed into once sleepy downtowns." Even Palo Alto, home of Stanford University and Xerox PARC, has turned on its kin, enacting an emergency ordinance in late October that bans companies from street-level retail spaces.

But the battle over gentrification is, in some ways, just a surface skirmish obscuring a more fundamental clash -- a struggle over the merits of technological progress itself.

Americans have always had a love-hate affair with technology. Ever since Eli Whitney memorized plans for the cotton gin and brought them to U.S. shores, Americans have struggled with whether the sociocultural changes wrought by new technologies are to be ultimately appreciated or denounced. The Net, despite its revolutionary nature, appears to be no exception. Like electricity, nuclear power, the automobile, airplanes and television before it, the Internet inspires both love and hate.

What's so interesting about today's incarnation of American techno-schizophrenia is, first, how fast love turned into hate -- after all, it really wasn't that long ago that the "empowering" and "democratic" possibilities of the Internet were being endlessly hyped in every cafe from San Jose to Sonoma. And second, how the two sides in the current debate in San Francisco -- the anti-growth protesters whose civic strength draws on a long and proud history of local progressive politics, and the dot-com boosters who are convinced that they are single-handedly ushering in a new economic golden age -- are intimately connected.

The computer culture and the counterculture grow from the same soil in the Bay Area. Dot-commers are just as much an organic outgrowth of local conditions as are the half-naked bands of tribal drummers that, given the slightest excuse, roam down Market Street in broad daylight. If one side devours the other -- if, for example, venture capital greed snuffs out art and culture, or crusading activists strangle new economy growth, San Francisco, and by extension the world, will be all the poorer.

Was it really just a few years ago that the employees of South of Market dot-coms would gather in South Park to celebrate such events as the defeat of the Communications Decency Act? Today, you are much more likely to see a funeral march full of people falling on the ground mimicking death, doubled over in dramatic tears or chanting "Take it over; shut it down" before a closed, empty City Hall. A walk through neighborhoods like the Mission District reveals anti-yuppie posters and "colonizer" graffiti painted on live-work lofts, and protests or sit-ins at nearly ever corner. The Bay Guardian's 34th anniversary issue, two weeks before the elections, treated readers to a 13-story spread on "The Battle For San Francisco." Still not sure who's fighting who? Read "The Dot-Com Road to Ruin" and have it spelled out for you.

Rhetoric, though, is only half the story. There's also policy. This summer, Walker and other anti-growth activists put a proposition on Tuesday's ballot that would essentially cut off development on 85 percent of the city's commercially zoned land. Given that vacancy rates hover around 2 percent and the city's office rents are the highest in the nation, most dot-com businesspeople argue that such legislation is exactly what the city does not need. Desperate to provide another alternative, San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown -- who many liberals long to punish for his long record of sucking up to developers -- has sponsored the less strict Proposition K, but even that would still only allow about 25 percent more growth than L.

There is little question that Prop. L adherents have a legitimate gripe. Those who are fighting the changes wrought by the dot-com boom have valid complaints, says Paul Tiffany, a business and economic policy professor who splits time between the University of California at Berkeley and the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania.

"Low rents are gone," says Tiffany. "And a very real argument can be made that a thriving and successful city is not a city of one industry. Diversity is the key." Yet, he and others argue that many of the proposals on local ballots are at their core "I've got mine, screw you" reactions that may or may not actually make things better.

The cavalier dismissal of anti-Net critiques are equally suspect. Both the protesters and, to pick just one example, the Web workers at NetSlaves who recently told San Francisco's "whiny preservationists" to "shut the fuck up" -- are suffering from collective amnesia, says author Howard Rheingold, who has chronicled the computer era in a string of books.

Technology is not an import to San Francisco. Rather, "the computer industry, the software world, the Internet -- they all have a direct connection to the San Francisco counterculture," he says. "Taking a long look at this thing, there are several different economic and technological revolutions that took place right here." But already, far too many people "have no memory of the digital revolution," Rheingold says. "It's for them about as far away as the Summer of Love."

Scratch under the surface of companies like Cisco and Sun -- two companies that are part of the true backbone of the new economy -- and you are as likely as not to find an aging hippie who originally saw the personal computer as a tool with which to bring down The Man. The savage irony, highlighted by the dot-com boom, is that that same tool ended up ushering in an era of economic growth that has swamped everybody, and brought down the heavy hand of The Man (this time in the guise of the venture capitalist) harder than ever.

The Net was "the sparkplug" that fired up the American economy and pulled us out of recession, says Tiffany. Even more dramatically, suggests Peter Leyden, coauthor of "The Long Boom," the Net altered the way Americans viewed themselves and their country.

"In 1990 everyone thought we would be working for the Japanese," he says. "There was a real sense that America was in decline and that there was nothing we could do about it. We had a slow-growth economy, high unemployment and a lot of crime. We had a perspective on the future that was very pessimistic."

It took an extremely fertile period of technology innovation -- improvements in battery-life, in microprocessor speed and especially the Net -- to change all that. "You wouldn't want to live in a world without it," Leyden says.

Indeed, even if you're not one of the 7.4 million Americans working in the high-tech industry, it has still made you richer, argues Brad DeLong, an economics professor at UC-Berkeley. Because computers have increased productivity, companies have made more with less and in many cases, passed on the savings. Everyone benefits. In fact, Wal-Mart shoppers were probably the first people to benefit from these technology-inspired savings, DeLong notes.

"For 50 years people have been saying that there are huge economies of scale to be taken advantage of in retail, but no one could pull it off," he says. "Then the '90s come along and everyone can buy things they want cheaper than ever before at Wal-Mart. They can do this because Sam Walton invested millions of dollars in computers and satellites, setting up a network that every employee could use."

"When you look at the benefits of the new economy," he adds, "you have to realize that those who are benefiting aren't just the wealthy."

The rationalizations of economics professors are small consolation, however, to a musician whose rent just tripled, or whose practice space just was converted into a dot-com office building. And it is crucial to make a distinction between the changes wrought in how businesses can operate and people can communicate with each other by the Internet, and the exploitation and speculation that has been layered on top of the digital revolution by the all-devouring force of venture capital greed.

Netscape, initially lauded as a Bay Area hero, can be seen as the villain that got venture capitalists focused on the Net. Once the browser company went public in August 1995, investors came running. By 1997, according to figures kept by the San Jose Mercury News, VCs invested about $200 million per year in local Internet companies, 20 percent of the $1 billion they gave to companies throughout the Bay Area.

Then the real money started flowing. In the fourth quarter of 1998, Bay Area investment started a sharp climb, spiking from about $1 billion to about $7 billion for this year.

Nationally, this mad rush helped accentuate a widening gap between rich and poor, says Jerry Mander, president of the International Forum on Globalization, a co-sponsor of the critical ad campaign running in the New York Times -- including one ad titled "The Internet and the Illusion of Empowerment."

"The Net is serving the concentration of power and a small number of global corporations," says Mander.

Locally, venture capital widened the gap between rich and poor as well. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the world of real estate. The average technology worker makes $58,000 -- 85 percent more than the national average -- which means that the average dot-commer can pay a whole lot more in rent.

The same goes for their companies. "No nonprofit can compete with a dot-com that has venture capital funding," says Debra Walker. "It's just not fair."

Plus, the dot-coms made things worse by "lying about what they are," says Sue Hestor, an anti-growth attorney who drafted Prop. L. To avoid the city's present cap on office growth -- a measure passed by voters in 1986 -- dot-commers started classifying their buildings not as "offices," but rather as "business services" or "multimedia" spaces. So, when office rents started to skyrocket over the past year to where they are today (ranging from about $65 to $100 per square foot), it was an all or nothing game -- "those who were backed by VCs were in, everyone else was out," Walker says.

Cultural organizations suffered. Art Explosion, Theatre Rhinoceros, Dancers Group Studio Theater, American Indian Contemporary Art Group, S.F. Camerawork -- these are just a handful of the arts groups that have lost their leases in the past year. And more are on the way, according to one analysis.

These evictions tend to inspire the most anger among those who are lashing out against technology-inspired growth. "It's ridiculous," says Kevin Barnard, a musician who pays his rent by designing Web pages, and who used to practice at a rehearsal space downtown from which bands were recently evicted. "The arts in this town are being clear-cut." Eventually, he says, this city will be filled only with rich people and nice offices. "What kind of legacy is that?" he asks.

It hasn't taken much of a jump for artists to translate their anger at gentrification and real estate speculation into antipathy for the Internet and the new economy in general. Thus comments like artist Megan Wilson's that "the new economy has done nothing for culture."

But such rhetoric inspires a counter-reaction from the technology elite.

"The Net has made more kinds of culture accessible to more people than any medium since the printing press," says David Touretzky, a Carnegie Mellon computer science professor who testified in the high-profile case regarding DeCSS, a program that enabled the viewing of DVDs on computers running Linux-based operating systems.

It's also broadened the cultural mix, says John Gilmore, a co-founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation and one of the earliest employees of Sun Microsystems. The Net, he argued in a lengthy e-mail, has made art more freewheeling than ever before by "rolling back some of the censorship we've seen in video, radio, books and art; creating easy and free instant written conversations with anybody no matter where they are in the world; employing hundreds of thousands of graphic artists whose previous prospects included being penniless or drawing ads; and making it so cheap for individuals to share information that even the greedhead record companies, which make something for 50 cents, sell it for $16, and keep 99 percent of the money deserved by the musicians, are afraid they can't make a living."

Extremist positions on each side have fueled both the local debate over the merits of the new economy in San Francisco and the national dialogue. For every outraged activist like Sue Hestor, who can barely talk about dot-coms without swearing, there is a techno-apologist like Touretzky, who says he has no sympathy for people "whining about property prices."

More space needs to be given to voices that can negotiate a middle ground. People like Michele Turner, 33, a Berkeley filmmaker who is sympathetic to artists but whose documentary "Digital Schoolroom" focused on how computers are changing education; or Rachel Riggan, 27, and Daphne Bernard, 26, graphic designers who have protested for the arts in San Francisco but consider dot-com scapegoating unproductive, even violent.

Meanwhile, less powerful dot-commers have banded together into groups like the Digital Workers Alliance, a group of technology employees dedicated to saving the arts. At least one group, Hip4SF, has gone even further, setting up an online bulletin board where artists and philanthropists can meet.

People in this crowd tend to separate the economic and cultural benefits from the unintended consequences. "It's a complex issue," says Louisa Van Leer, an architect who works in the Mission and has been mistaken for a dot-commer. The focus should be on people, she says, not technology. "No one was here first; it's just a matter of making room for everyone," she says.

Even if people don't realize it at first, "Technology is always a double-edged sword," says Ray Kurzweil, inventor of the first music synthesizer to mimic a grand piano and other orchestral instruments.

"The world with the Net is not 'better' so much as 'different,'" says Bill Joy, chief scientist at Sun and author of a now famous Wired magazine article that called for computer scientists to take more responsibility for their actions. "If we work to accentuate the many positive things, the wealth [technology] creates should be accompanied by many good things, as well as some bad ones. Since the Net isn't going away, this seems to me to be the constructive thing to do."

I couldn't agree more. When I came to San Francisco just over a year ago, I didn't know much about the Net's radical roots, nor did I realize that I would soon be pressured to choose between the two reasons I moved here: my dot-com job and the arts. But I've learned a lot since then, including how not to choose, how to separate the technology from the greed that's accompanied it.

What's so frustrating is that others have not. The present debate has less to do with logic than with anger -- at Willie Brown's penchant for overdevelopment, at dot-commer greed and at activists who claim to be fighting gentrification, but actually care only about getting attention. Few protesters or dot-commers seem to realize that these feelings, however justified, only damage technology and the arts by driving a wedge between them. This wedge is not natural; culture, counterculture and the Net belong together. Yet, anti-dot-com development protests still gather 400 to 1,000 people while diplomatic meetings -- like one held Oct. 25 to discuss solutions, "not Prop. L or Prop. K" -- draw no more than 80. Forget development, dot-com greed and activist sanctimony, this is what needs to change. Enough with the funerals; let's plan a marriage.

Shares