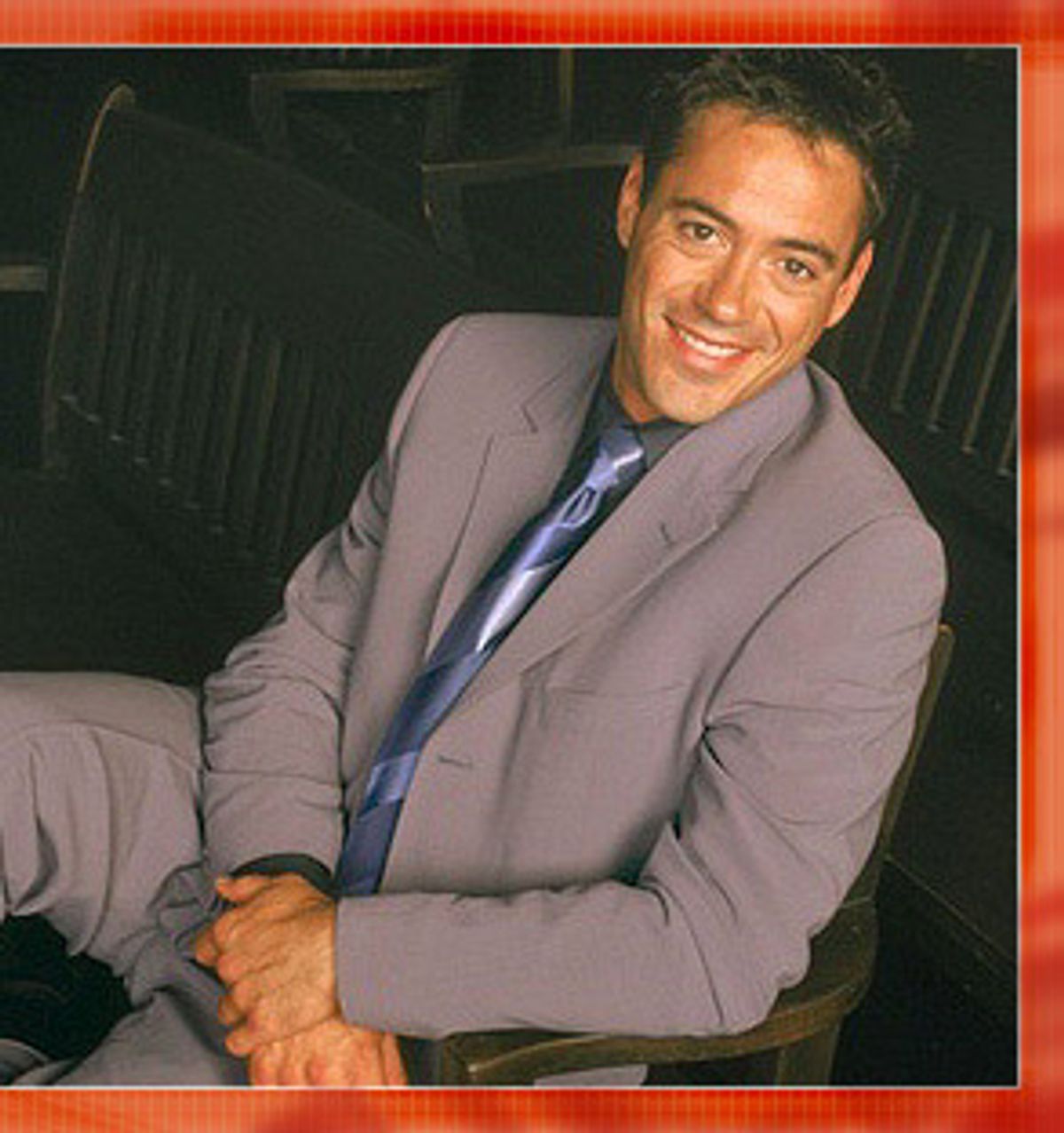

Is there any way to confer protected status on an artist the way we do on art or other endangered species? Robert Downey Jr., who was arrested last Saturday for drug possession, is never likely to settle into the prestigious roles that win performers the phrase "national treasure" and late-career accolades at the American Film Institute or the Kennedy Center. But I mean that as a compliment. He is constitutionally incapable of wallowing in sentimentality or bloating into self-importance. On big screens or small ones, in comedy or drama, he moves through dark and light emotions like unique multicolored quicksilver, sluicing to the heart of elusive characters like the bisexual editor in "Wonder Boys" and the slick yet melancholy lawyer in "Ally McBeal." He illuminates their odd angles with modulated merriment and rage or stinging bolts of imaginative sympathy.

Downey is the most extravagantly gifted actor of his generation. A more humane society would grant him better treatment and more solace than the punishment and tepid sympathy that awaits him in the courts and in the press. In San Francisco, in the commercial breaks during Monday's episode of "Ally McBeal," the Fox station promoted its 10 p.m. news broadcast with a mug shot of Downey and clips of his previous trips to court, previewing an earnest but flaccid report about the difficulty of controlling or recovering from addiction.

This is the destiny of celebrity drug addicts circa 2000: exploitation and moral bromides, followed by prison. Scholars love to say that show-biz superstars are the equivalent of 18th century aristocrats, living out wild, appalling scenarios that lesser beings can only fantasize about. This idea overlooks the petty, punitive aspect of our country's celebrity worship. Too often we sacrifice our entertainers and artists to the fears of the middle class and its reluctance to face controversy. Downey doesn't pretend to be a role model and has harmed no one except himself. As "Wonder Boys" director Curtis Hanson told me the last time this actor got in trouble with the law, throwing an addict like Downey behind bars will one day be deemed as barbaric as treating the ailing with leeches.

James Toback, who directed Downey in "Two Girls and a Guy" and, brilliantly, in "Black and White," said last spring that Downey's troubles have made him a more probing artist. That's a positive way of looking at his plight, but I don't agree. Toback never gave Downey a better showcase than when he first collaborated with the actor way back in 1987, in the seductive light comedy "The Pick-Up Artist."

In this burgeoning cult movie, Downey plays a schoolteacher who spends as much time cruising the sidewalks of New York as he does coaching his students in history or softball. He's a guy with classic rock and roll in his heart -- a seemingly eternal adolescent who can da-doo-ron-ron even when his Chevy Camaro convertible won't ra-run-run-run. And the conviction Downey gives this youthful Don Juan is downright disarming. In the best possible way, the actor, like the character, gets carried away by his own act. When he goes into a favorite spritz -- "Did anyone ever tell you," he asks Molly Ringwald, "you have the face of a Botticelli and the body of a Degas?" -- you glimpse the depths behind Downey's lustiness. First Downey makes you believe that his character is an epic skirt chaser: to use Milan Kundera's definition, the man pursuing a variety of women to sample their individuality. Then he makes you believe that he's turned into a lyrical skirt-chaser, searching for his feminine ideal.

Downey has done much of his best work in films that never broke through to big audiences. In 1989, director Joseph Ruben brought out a sensational courtroom drama, "True Believer," which proved Downey could be as terrific a sidekick as main act. Downey remains the best foil ever for the movie's star, James Woods: He is just as intelligent and far more fluid an actor, and the way he plays the wet-behind-the-ears associate to Woods' burned-out radical attorney, his idealism doesn't just prod the veteran -- it needles him, lovingly yet mercilessly. Sadly, the flopping of "True Believer" put a roadblock in Woods' attempt to become a leading man. But it didn't stop Downey. Three years later he won the part that would earn him an Academy Award nomination, the rapt attention of directors and the outright awe of his peers.

In the title role in "Chaplin," Downey embodies the slapstick genius's distinctive blend of spunk, poetry and enigmatic sensuality -- of balletic grace and robust knockabout farce. The movie is diffuse, gimmicky and damnably respectable, but Downey gives it the kick in the pants it needs. The script locates the source of Chaplin's pathos-laden creativity in his early years with his mad mother, and Downey adopts some of her unhinged look, surrounding his character with an aura of free-floating emotion.

Downey is an extraordinary physical mimic: His deftness and agility make the loose recreations of Chaplin's evolving style fun to watch. But Downey's suggestion of an unruly interior life is what keeps the movie alive. The best parts of "Chaplin" come together when the exiled hero, banned from this country since the McCarthy era, returns to receive a special Oscar at the 1972 Academy Awards presentation. When you see the film clips shown to celebrate the occasion, the excerpt from "The Kid" is overpowering, partly because of the connections between that film's Dickensian milieu and Chaplin's troubled youth. And Downey is amazing as the elderly Chaplin. It's a tribute to Downey that when the film cuts to Chaplin's eyes filling with tears as the Tramp embraces Jackie Coogan in "The Kid," the moment isn't sticky or embarrassing. It's transporting.

If "Chaplin" remains Downey's career high point, it's because of the scope it afforded him. Downey was wonderfully funny -- the most elaborately baggy-pantsed clown you could imagine -- in the tart first half of Michael Hoffman's costume picture "Restoration." (He had previously limned a slimy soap producer for Hoffman's hilarious "Soapdish.") And he briefly jolted Mike Figgis' all-too-tony "One Night Stand" back on its feet as a dying AIDS patient who provokes an old friend to feel and tell the truth. He's rarely been more sly, daring or touching than as the gay husband of Brooke Shields in "Black and White" -- especially when he comes on to Mike Tyson -- and in "Wonder Boys" he holds down his position in a crackerjack ensemble with a controlled euphoria unlike anything I've seen since Jack Lemmon in his Ensign Pulver days.

In "Ally McBeal," Downey has, against all odds, introduced a streak of wary sanity into creator David E. Kelley's cockeyed universe -- and has somehow grounded Calista Flockhart's giddiness in his own loamy emotions, which range from the ballsy to the bluesy. When Downey sang on the show Monday night, his melodious hoarseness had a soulful, lyric rapture that both pierced Ally's heart and frightened her. In the course of the episode, Ally admits that she fell for him because he lifted her up; now she worries that he's carrying around a grief and despair far greater than her own. She voices the confusion of the actor's own admirers. In the end, she stands by him.

May Downey's fans do the same.

Shares