One of the pillars of Freudian theory is the castration complex -- boys' unconscious fear that their fathers will chop off their penises, girls' unconscious anxiety that they once had penises that were chopped off. Which leaves everyone fixated on the phallus (or at least on Freud). But in "Castration: An Abbreviated History of Western Manhood," Shakespeare scholar Gary Taylor surveys Western culture through the ages and responds: balls.

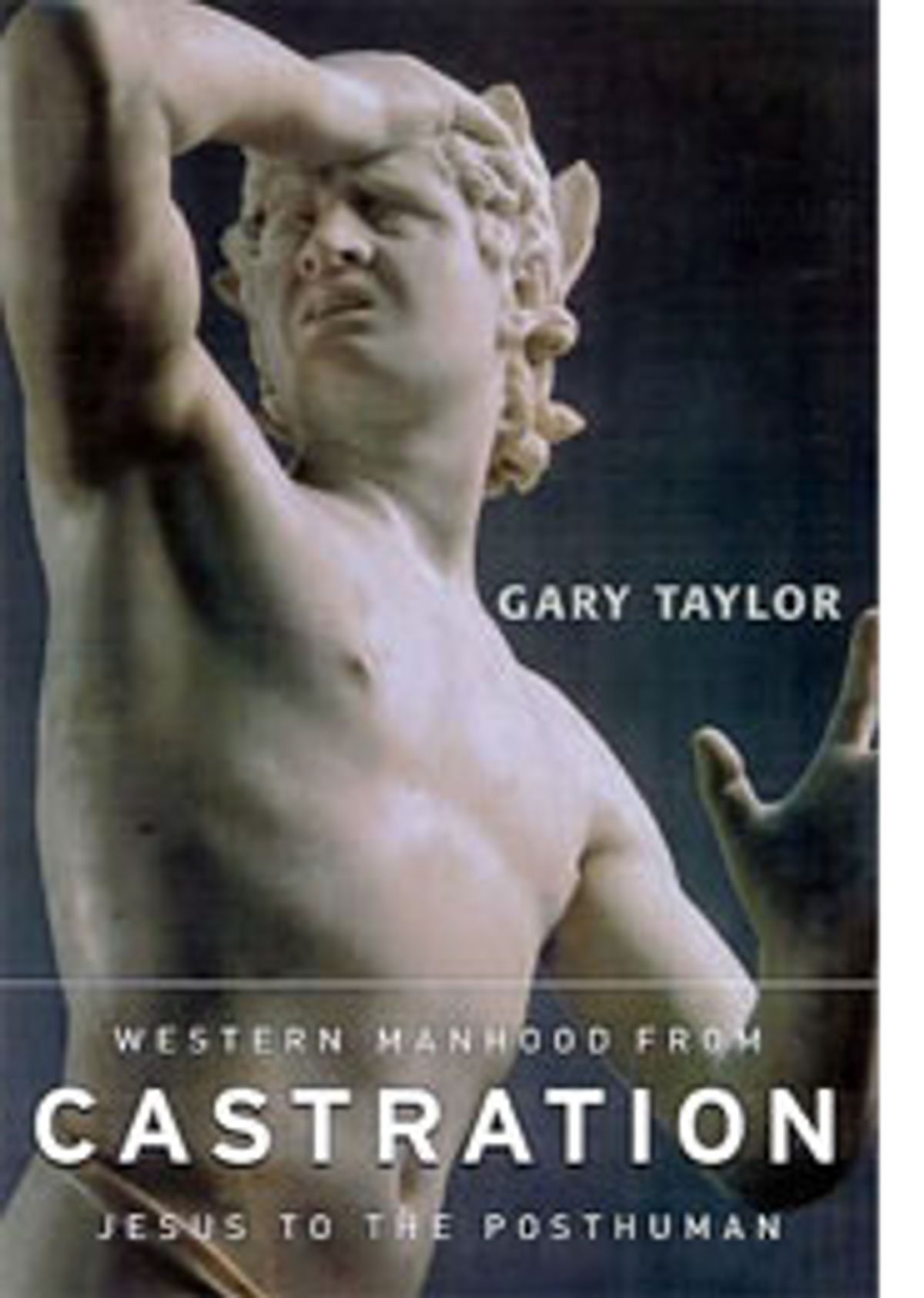

This dense, scholarly yet thoroughly entertaining book examines the uses of castration -- a word which, before Freud, never meant removal of the penis, only the testicles -- along with thousands of years' worth of popular attitudes about male genitals. Taylor -- who gained notoriety for arguing in 1985 that a ditty titled "Shall I die?" was written by Shakespeare -- posits that understanding what it means to be biologically unmanned is an excellent way to understand what it means to be a man. You don't need to be enthusiastic about this thesis -- or even to be male -- to find "Castration" terrific reading.

"Freud's theories about castration anxiety and the penis envy of castrated females," Taylor writes, "can hardly be an accurate description of 'patriarchy,' because they misrepresent almost the entire history of castration and almost the entire history of patriarchy." Psychoanalysis reflects what Taylor calls "the rise of the penis" in Western culture, accompanied by the corresponding "fall of the scrotum": In our thinking about sex over the past few hundred years, reproduction has steadily ceded the floor to pleasure; the family jewels, which used to be considered a man's dearest possession, are now just ornaments on the scepter. In one emblematically ridiculous instance, Taylor reports, the copy of Michelangelo's "David" installed at Caesar's Palace had to be taken down and fitted with a new porn-star schlong because the original penis-to-scrotum proportions looked so absurd to modern connoisseurs of beefcake.

Until fairly recently, amputation of the penis for either medical or punitive reasons generally caused death from loss of blood. But many cultures established a place in the social and moral hierarchy for eunuchs -- who Taylor says were usually castrated in so-called savage societies for sale to so-called civilized ones, so that eunuchs would not have to serve their own mutilators. In Rome they were slaves, but Taylor reminds us that in the Assyrian, Persian, Byzantine and Ottoman empires, not to mention the Far East and Africa, eunuchs sat at the highest levels of the court, responsible for granting or withholding access to the emperor or administering justice in his name. And Abelard (of Abelard-and-Heloise fame), following his castration, was an important figure in the medieval Christian church.

Taylor's scholarship and eloquence blaze in his discussions of Augustine and other early Christians. Writing in the fourth century, Augustine jumped through hoops to justify Matthew 19:12, in which Jesus speaks well of "eunuchs, which have made themselves eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven's sake." Augustine -- "a rhetorician before he was a saint," Taylor points out -- interpreted this as an allegory for priestly celibacy, much as Paul had eased the gentiles into accepting Christianity, an offshoot of Judaism, by requiring of them only a "circumcision of the heart," not actual foreskin-hacking.

Taylor proposes that the literal interpretation of Matthew 19:12 is just as likely, given that Jesus' teaching would have appealed most to eunuch slaves, surely the meekest of the blessed meek. But politically, the church fathers had to distance the new religion from the still-thriving pagan cults involving self-castration, which many early Christians, taking Jesus' words literally, practiced too. Taylor gleefully ruffles feathers by identifying Jesus' "radical hostility to heterosexual marriage and reproduction": Among other things, Christ blessed the barren and specifically promised everlasting life to those who forsook their families for him. So, Taylor argues, according to the Gospels, Jesus actually deplored Christian family values. Did he encourage gruesome self-sterilization?

Taylor subverts your expectations at every turn. I've put off mentioning that much of "Castration" revolves around a close analysis of playwright Thomas Middleton's 1624 tragedy "A Game at Chess," a deeply weird-sounding political allegory in which a black chess piece (representing a Spanish Catholic) castrates a white chess piece (an English Protestant). I'd never heard of it either, but Taylor knows we haven't read it. Taking off from the play, he discusses the way eunuchs' genitals mark them as a race the same way circumcision marks Jews; racially, Middleton and other northern Europeans perceived the Spanish as dark-skinned aliens, just as Augustine and other olive-skinned Romans showed a prejudice against northern Europeans -- and eunuchs -- for their pallor. The play, which Taylor says is up there with Shakespeare, is the catalyst for an avalanche of absorbing speculations about racism, incest and power relations in sex, religion and politics.

Eunuchs have often been seen as monsters, neither male nor female -- especially those castrated before puberty, who become obese and pale and can't have intercourse, such as the castrati who used to sing in operas (and Catholic choirs). But a eunuch castrated in adulthood is often perfectly capable of sex. Taylor addresses Freud's boneheaded question "What does woman want?" by discussing vasectomy as a modern update of castration and suggesting that in the overpopulated 21st century -- as "abnormal" sexual and gender identities are increasingly accepted and science plunges into cloning and artificial genetic manipulation -- a eunuch is exactly what many women want. This insight probably won't make anybody reach for the pruning shears, but it's the kind of witty provocation that makes "Castration" an improbable delight.

Shares