Over beers and green curry in a tiny village near Thailand's border, I ask my dinner companion whether he thinks the leaders of the Khmer Rouge should finally be tried for war crimes, 25 years after they oversaw the slaughter of more than a million people. He leans forward and pauses. "I want a trial," he says at last. "Every leader does good things and bad things. Bad things were done."

He ought to know. Like countless Cambodians, Meas Tung joined the Khmer Rouge as a teenager during the early 1960s. At age 13, he was swept up in the organization's romanticism about ethnic Khmer pride, and its calls for people to get back to the land. He became a combat soldier at 17, and tells me he helped plant some of the hundreds of thousands of land mines, booby traps and explosive devices still buried in fields across Cambodia.

By the time the Khmer Rouge launched its brutal assault in 1975, soft-spoken, dimpled Meas was a seasoned fighter. And by the time he quit the organization in the early 1990s, he had climbed through the ranks to become the head of a regiment, and a colonel in the army of Pol Pot, one of the most eccentric and brutal dictators in modern history. Meas was even summoned to Pol Pot's jungle hideout in 1993, only a few miles from where we are now sitting eating dinner, to hear an address by the revered Brother Number One, about the internationally brokered Paris agreement that ended Cambodia's decades of war.

Culturally, Cambodians have focused their efforts on reconciliation with former enemies, and there is a widespread fear that a war-crimes trial would disrupt that process. But the horrific past lives on in this country, in piles of skeletons dug up from mass graves and made into shrines and in the stories of the regime's survivors. And pressure from the United States is mounting, meaning the process of justice might soon be underway.

In just 44 months between April 1975 and January 1979, the Khmer Rouge executed, tortured to death or effectively starved between 1.5 and 2 million Cambodians -- nearly 1 in every 4 people -- in killing fields across the country. Clocks, radios, televisions, all Western medicines, books, hospitals, stores and schools were banned during the Khmer Rouge genocide years. Teachers, doctors, even classical dancers, were forbidden to practice and thousands of them were executed. Khmer Rouge soldiers smashed thousands of wooden buildings in Cambodia's gracious old colonial capital of Phnom Penh, to sell the wood to the Vietnamese.

But ask Meas Tung what he did during the genocide of Cambodians and you are not likely to learn much. "I was taught to repair trucks, and guarded a yard where trucks were kept," he says, watching every word. "Later, I patrolled a big road."

Like hundreds of former Khmer Rouge soldiers, Meas has not only blended into Cambodia's new society but has been scrubbed clean of the past. He now heads the agricultural program for the district of Samlot, which runs along Thailand's border. On this day, his task is to escort two foreign journalists around the area, to show them the land on which thousands of refugees and demobilized soldiers are now living and farming.

More than 25 years after the Khmer Rouge routed Cambodia's capital, Phnom Penh, and began its mass murder campaign, United Nations and American officials are nearing a deal to try some of those culpable. After more than two years of negotiations, delays and objections, Cambodia's Prime Minister Hun Sen has promised to pass a law within the next month clearing the way for a war-crimes trial. There are hitches, however: Contrary to the original international plan, the trial will take place on Cambodian soil, in Phnom Penh, and involve both Cambodian and foreign prosecutors and judges. Even then, the foreign jurists will have to be approved by Hun Sen's government. The deal is a slippery slope, one which many human rights groups believe will water down the impact of the trials.

The very mention of Cambodia has for years evoked images of genocide in the minds of Westerners, whose vision of the Khmer Rouge was immortalized in Roland Jaffe's movie "The Killing Fields." Then in the 1990s the horrors of Bosnia and Rwanda arrived to match those ghoulish associations. Yet there remains one crucial difference to set Cambodia apart: Both the Balkans and Rwandan wars have resulted in war-crimes tribunals, with Serbs on trial in The Hague and Rwandans in Arusha, Tanzania. Cambodia, by contrast, has yet to try a single official.

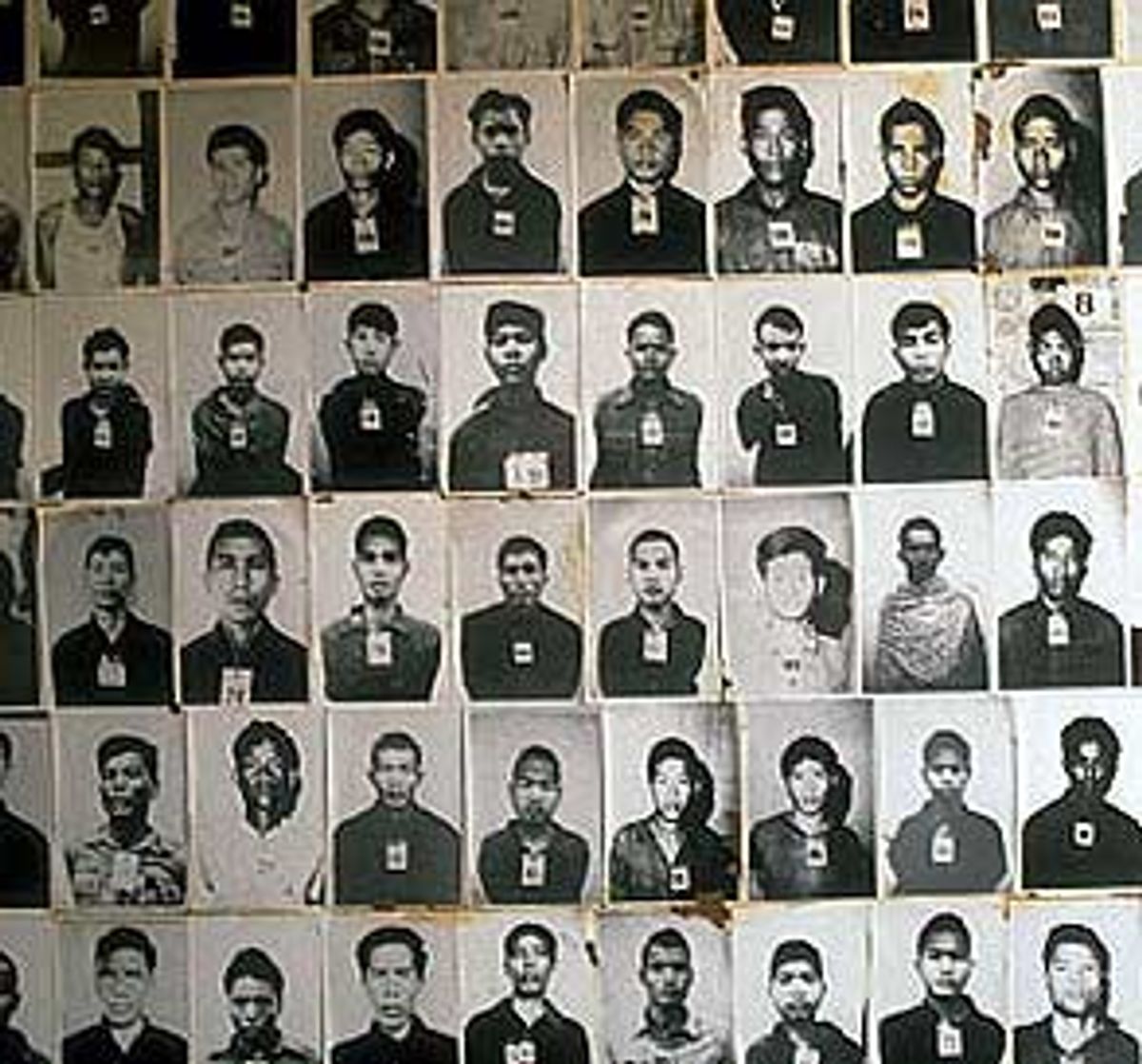

Only two Khmer Rouge officials have been arrested: military chief Ta Mok, nicknamed "the butcher," and Duch, or Kang Kek Ieu, who ran the infamous Tuol Sleng S-21 prison, a torture and death center in Phnom Penh, where about 18,000 people died. Hundreds of other Khmer Rouge officials have slipped comfortably back into society. Duch himself had been working for an international aid organization near the Thai border until journalists spotted him, having recognized his face from the old days. And Pol Pot died suddenly -- perhaps by suicide -- in April 1998, maddeningly on the verge of being arrested.

Cambodian officials have long balked at putting the nation's history on trial. Partly, they recoil from the idea of foreigners snooping into their affairs. More importantly, there are real fears that any trial could expose present-day officials, several of whom were active in the Khmer Rouge during the 1970s. Hun Sen himself, now 48, spent years as a Khmer Rouge fighter, even losing an eye during the 1975 invasion of Phnom Penh. And Pol Pot's own deputy, Ieng Sary, keeps a low profile at home in Phnom Penh. Other key Khmer Rouge leaders live in Pailin, an old stronghold near the Thai border. And in remote areas like the villages of Samlot, where I share dinner with Meas Tung, the district's agricultural chief, almost everyone owes old allegiances to Pol Pot's fighters. "We have a saying in Cambodian: 'When the water clears, you can see the small fish,'" a Phnom Penh journalist tells me. "So, a trial can point to a lot of people."

It might seem surprising that a veteran Khmer Rouge soldier like Meas would want a trial. He seems to believe the process would finally distinguish the communist ideals of the Khmer Rouge -- ideals that seduced many Cambodians -- from the horrors that were committed in the name of the cause. He says many of his old comrades "killed their own people," and for that, should be convicted. But, he says, "Many people around here think differently."

Despite international pressure, few in Phnom Penh have believed that a trial would ever come to pass. Then came President Clinton's trip to Vietnam last month, with its promise of American aid and closer diplomatic ties. The visit was downplayed in the jittery Vietnamese press, but the full pomp and ceremony played big on CNN and was watched by officials in Phnom Penh. Massachusetts Sen. John Kerry, traveling in Clinton's Vietnam entourage, seized the moment. He made the quick side trip to the Cambodian capital to meet Hun Sen, and told the prime minister that if he ever wanted to welcome an American president to Phnom Penh, he had to put the Khmer Rouge on trial.

American representatives have set out to show the Cambodian government that they're serious about justice. The U.S. government has funded the Cambodian Genocide Project at Yale University to investigate Khmer Rouge crimes. "We've collected thousands of documents," a Democratic staffer of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee tells me on the telephone from Washington. "We had to make it clear to the Cambodians that we were not just doing this as an academic exercise," he says. "There are Khmer Rouge leaders walking around with impunity."

At stake for Hun Sen is desperately needed foreign aid. Cambodia's average annual income is less than $300. Outside Phnom Penh, most roads crumble into muddy, rutted passes that have barely seen a dollop of tar for 25 years. It takes nearly four hours to drive a pickup truck over about 30 miles of dirt road between Cambodia's second city, Battambang, to Samlot, along what used to be the major trade route to Thailand.

Around Phnom Penh, there are few signs of the devastation. The markets are teeming with traders selling fruits, batik textiles, cheap Korean toys, electronics and luggage with wheels. The traffic is thick with Honda motorbikes that buzz around town offering rides anywhere in the capital for 50 cents, along the old French colonial boulevards with wide islands that run along the gracious yellow-and-blue buildings. Most Cambodians are now too young to have any personal memories of the genocide. And astonishingly, there is no mention of it in Cambodian schoolbooks. Human-rights groups are only now raising money to produce children's books telling them what their parents endured.

But travel Cambodia, and you will still hear countless tales of horror. "My father was a French teacher, so we were sent to a farm to work in the rice paddies," says my translator, adding that several of his siblings died of starvation after the family was evacuated from their home in Battambang. One of Cambodia's best known classical dancers, Proeung Chhieng, tells me he survived the genocide partly by hiding for months in the forests and not telling anyone that he had danced in the royal palace in Phnom Penh since he was 8 years old.

Outside the capital, several villages have simply gathered their skulls and bones into small shrines. People used to pay homage to the dead once a year on the date the government had designated "Hatred Day," the anniversary of the Khmer Rouge's ban on family meals. The day was officially abandoned a few years ago, but the shrines remain. In Phnom Udong, about an hour's drive outside Phnom Penh, a glassed-in memorial shows a pile of bones and skulls that stare out at villages in the middle of the marketplace. And alongside a Buddhist temple in a community in Kompong Speu, a wooden shed shelters a small mound of skeletons dug up from mass graves in the village.

Yuok Chhang, 40, who runs Cambodia's Documentation Center set up by Yale University's genocide project in 1995, tries to list for me the victims among his own family. "Let's see, there was one sister and her two children, one brother-in-law, one aunt, four uncles," he says, and then adds, "You know, it's easier for me to count those who are alive than all the ones who were killed." Chhang travels between Phnom Penh and Dallas, to where to his parents emigrated while he was a teenager. Amid the Dallas Cowboys knickknacks in his office, walls of filing cabinets now hold about 600,000 documents, statements and photographs that could be used in war-crimes trials. Sitting in the center's conference room surrounded by 25-year-old photographs of genocide victims, Chhang says the country is still reeling psychologically from the aftereffects. "We all look fine, we're wearing nice clothes, but mentally we are still living in the past," he says.

In fact, Cambodians are still counting the cost of the Khmer Rouge's destruction. On the wall of a room in the Tuol Sleng prison, which now serves as the country's genocide museum, there is a handwritten list of what was obliterated: 3,314,768 killed or disappeared; 635,522 buildings destroyed; 1,200 communes, or villages, "completely effaced."

On the prison walls, thousands of blank faces of Cambodians stare out at the next generation. Photographed by the Khmer Rouge with macabre precision moments before their execution, they are the closest thing to a witness list that prosecutors could use to try to convict Ta Mok, Duch and others. "I wanted to see the real pictures in here, because my parents used to tell me what happened to them," Sim Kamsan, a 20-year-old computer teacher visiting the museum on a Sunday afternoon, tells me there. To his generation, raised with MTV and direct-dialing to the West from mobile telephones, "it seems impossible that this will ever happen again."

Perhaps so. But whether those responsible will be convicted and sentenced is another matter.

Shares