In 1968, Kathy Kusner went to court to become a jockey in America. That same year, Penny Ann Early was ignored when she tried to get a mount at Churchill Downs, home of the Kentucky Derby. Jockey Barbara Jo Rubin's trailer was stoned in 1969. In those days most female riders became regulars at small tracks and never made a mark on big-time racing. Trainers and horse owners didn't think the "gentler sex" could handle the brutal, 1,200-pound beasts.

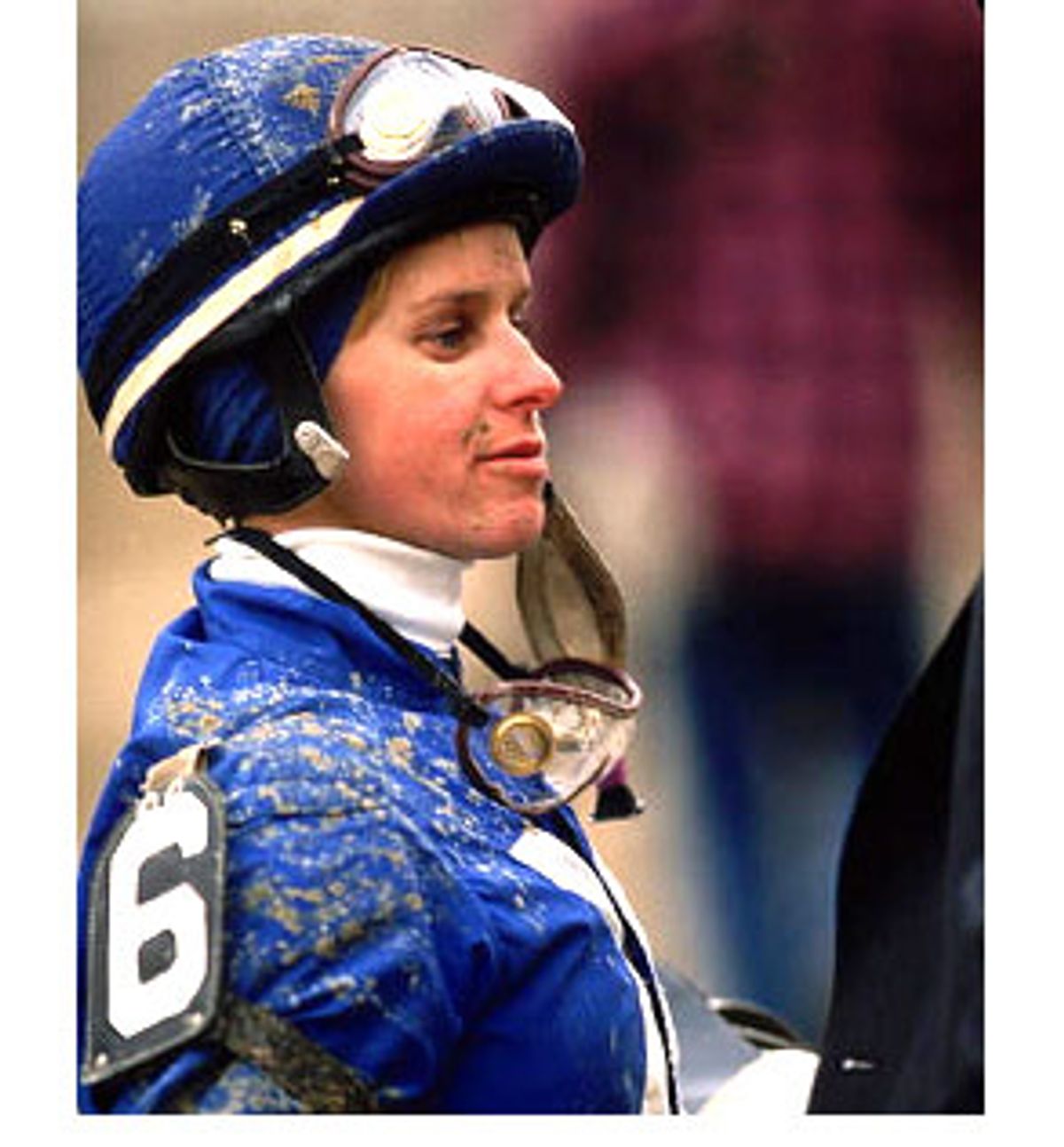

Then Julie Krone came along. At 4-foot-10 and 100 pounds, tiny even for a jockey (average size: 5-foot-3 and 110 pounds), the energetic blond with the high-pitched voice became the world's winningest female jockey and the only woman ever inducted into thoroughbred racing's Hall of Fame.

In a career that spanned 18 years Krone won 3,545 races and more than $81 million in purses. By the time she retired in 1999, she had put 17 percent of her mounts into the winner's circle. Kusner, Early and Rubin had paved the way for all the firsts in Krone's career, including first woman to ride in the Belmont Stakes and first woman to win a jockey championship at a major racetrack, among other distinctions.

Trainer John Forbes, who often worked with Krone, told USA Today this year that prejudice against female riders is "still out there, and I don't think it will ever go away. The notion that a rider has to be very strong and powerful so he can control a 1,000-pound animal and hit it really hard with a whip is something that has been ingrained. The resistance we had was unbelievable."

"It was like a girl playing shortstop for the Yankees," said Krone's then agent, Larry "Snake" Cooper, to London's Independent in 1990.

What Krone proved was that brute whipping ability isn't always the answer. From childhood on, she seemed to have an ability to communicate with her horses, to discover what made a horse want to work hard -- and what it needed for thanks.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Julieanne Louise Krone was born July 24, 1963, in Benton Harbor, Mich. She was raised on a farm in nearby Eau Claire, where her parents let her and her brother, Donnie, three years her senior, run wild.

The family never ate dinner together. Julie sometimes feasted on dog food with the dogs. At 5, she led her horse right into the house for her mother to saddle. Occasionally, she slept with her whip. At 9, she harnessed a Great Dane to a sled and went for a ride in the snow. At 13, dressed only in a deerskin tied around her midriff, she stood on the back of her galloping horse and headed into the barn, dropping to a sitting position just before the top of the barn doorway nearly decapitated her.

"I could count on one hand the times my parents made a meal for me, and it wasn't because we were poor," Krone told the New York Daily News in 1988. "I guess I never even realized it until one day when I was older and my friend from next door asked why there was never any food in my house."

Her father, Don, an art teacher and photographer, wouldn't stop his daughter from doing back flips off a horse. Instead, he'd ask her to do it again for the camera.

"Every day was a missile launch," he told Sports Illustrated in 1989. "Yes, there was always that element of possible disaster, but it was just like a missile -- if it goes, god, there's going to be that moment of glory. You can't tell a kid to go for it, to be whatever they want to be, and also tell them to be careful. If we all ride the safe road, who will we look up to? Who will be on the high road? No, we didn't worry about the little things."

Her mother, Judi, a riding instructor and former Michigan State equestrian champion, forged Julie's birth certificate when she was 15 so that she could get work at Churchill Downs as a groom and exercise rider. Why Churchill Downs, where she would have to move away from her family? "Because it's the logical place to become a jockey," Julie has said.

The night before heading to Kentucky, Judi Krone came home from her part-time bartending job at 1 a.m. to find Julie waiting up. Instead of shooing her off to bed, the pair rode their horses into the Michigan night, singing "Don't Fence Me In."

Setting off for Kentucky marked the beginning of Julie's professional riding career, but her relationship with horses had been going on since birth.

Julie's first time on a horse came at age 2. Her mother was trying to sell a palomino and plunked little diapered Julie on its back to demonstrate the horse's gentle nature. The horse immediately began to trot away. Julie's mother didn't bat an eye; she just kept trying to sell the horse. The horse stopped and toddler Julie reached down and grabbed the reins as natural as can be and tugged them. The horse turned and came back.

Krone won her first event at the age of 5 -- in a 21-and-under event. She continued riding and competing in horse shows, but when she was 14, her life changed.

That marked the year her parents divorced, but another 1978 event seems to have had a more lasting effect on Krone: Steve Cauthen, 18, won the Triple Crown on Affirmed. The jockey became her hero and she quickly read Pete Axthelm's Cauthen biography, "The Kid." She decided then to be a jockey.

"He was my inspiration," she has said. "I read his story and thought, 'If he could overcome all the difficulties, so could I.'"

The next year, though, her sophomore year in high school, she was invited to join a traveling circus as a trick rider and nearly did. At the last minute, she decided she didn't trust the guy running the show and went back to her jockey dream. When the school term ended she went to Churchill Downs, with no sleep and a forged birth certificate in hand.

She stayed for three months, earning $50 a week and living with an older trainer. The following summer, she raced in Michigan, Ohio and Illinois. Krone made it halfway through her senior year of high school before she felt the need to split again. Much to her teacher dad's consternation, she dropped out of school and headed to Tampa Bay, Fla., to live with her grandparents and work as an exercise rider and apprentice jockey at Tampa Bay Downs. But the guards wouldn't even let her through the front gate. So she and her mother walked down the length of fence and then climbed it. They started toward the barns only to be picked up by a woman who thought she had found a lost little girl and her confused mother.

The woman took Krone to her boyfriend, Jerry Pace, a trainer. "So," he said, "I'm told you want to be a jockey."

"No," Krone said, "I'm gonna be a jockey."

Pace took her out and let her ride, thinking he was merely humoring her. Five weeks later, in February 1981, she sat atop Lord Farkle in the winner's circle.

She began working her way up, battling fellow jockeys and winning lots of races. Most horse owners and trainers wanted nothing to do with a "jockette." She told USA Today this year, "I learned how to climb into people's hearts like you can't believe. I worked so hard to -- we will loosely use the term -- 'seduce' people."

Her seductions may have included the free doughnuts she was handing out or her bone-crushing handshake. Maryland horse trainer Ben Perkins Jr. told the New York Times about meeting Krone for the first time, at his barn in Atlantic City, N.J., in 1981: "This cute little girl, looks about 10, comes up to me and squeaks, 'Hi! I'm Julie Krone! I'm a jockey!' and takes my hand and brings me to my knees. Well, we let her ride, and she rides like a god."

More and more trainers started accepting the fact that Krone, despite her sex, could get the job done. "The perfect thing," Perkins continued, "would be this little small person who could just sit on the horse's back and go along for the ride, just to keep the horse out of trouble. That was Julie."

She could coax horses to win instead of pushing them. Trainers often spoke of her patience and her hands, which seemed to guide the horse to victory, no matter the odds. But she wasn't necessarily a gentle rider and, when necessary, she wasn't a gentle person.

In 1982, Yves Turcotte smacked her horse with his whip during a race and, when the race was over, Krone shoved him off the weigh-out scales. Jockey Jake Nied wrestled with her after a match until others pulled them apart. In 1986, Miguel Rujano hit her in the ear with his whip and she punched him in the face. He pushed her into the jockeys' swimming pool and she hit him with a lawn chair. In 1989, she exchanged blows with jockey Joe Bravo and left him with fewer teeth. She was fined for these infractions, but they gained her much respect.

That wild streak spilled over to her personal life. She drove a red Porsche with a wooden block on the accelerator so her short legs could stomp the pedal all the way down. In 1983, when she was racing at Pimlico Race Course in Maryland, authorities found marijuana in her car, a habit she had picked up when she was 12. According to Sports Illustrated, she was lucky they didn't find cocaine.

Krone attended a drug-rehab class and urinated into a jar once a week for the next year. But the most brutal punishment was the 60-day suspension. It was the first time in her life that she couldn't ride. It drove her crazy. She went to the racetrack and stood outside the fence. She went clean.

Upon her return, she continued to steamroll through boundaries (1987: first woman to win a riding title at a major track; 1992: first woman to ride in the Kentucky Derby; one of only a handful of American riders to win six races in one day) and victory tape. In the 1980s, she won 1,898 races. In 1986, her mother was diagnosed with cancer and Krone asked her what she could do for her. In a moment straight out of "Rocky," Judi Krone told her daughter that all she could do was win. And so she did.

In 1993, she reached her peak. She became the first woman to win a Triple Crown event, the 125-year-old Belmont Stakes, astride 13-to-1 long-shot Colonial Affair. She was named the person of the week by ABC News. ESPN gave her an Espy award as 1993's top female athlete. Krone was on top of the world.

After the race, she made it clear how she felt about being the first woman to break into the Triple Crown winner's circle: "I don't think the question needs to be genderized. It would feel great to anyone. But whether you're a girl or a boy or a Martian, you still have to go out and prove yourself every day."

Just two months later, Julie's life took a drastic turn. It was the last day of racing at Saratoga Raceway in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., and Krone's third race of the day. Her horse, Seattle Way, was in the middle of 11 horses at the top of the stretch when another horse veered into her path. Seattle Way's hooves became tangled with the other's heels and Krone was thrown free. She landed awkwardly on her feet and bounced grotesquely into a sitting position, and then another horse, aptly named Two Is Trouble, ran directly into her, kicking her in the chest. Her ankle was shattered. If she hadn't been wearing a 2-pound flak jacket, the kick might have killed her. As it was, she suffered a cardiac contusion, a bruising of the heart.

The ankle injury required two steel plates and 14 screws to repair. She was bedridden with morphine dripping into her arm. A friend brought her a horse brush that she called her "aroma therapy."

It took nine months for Krone to get back onto the racetrack. In August 1995, she married TV reporter Matt Muzikar. The same year, she published her autobiography, "Riding for My Life," written with Nancy Ann Richardson. Then on Jan. 13, 1996, at Florida's Gulfstream Park, she went down again, this time breaking both her precious hands.

"When I was lying there on the ground, I knew my life was going to change," Krone told the Associated Press this year. "And as I was getting ready to come back, I had trepidation." She had nightmares about falling. She got lost on streets she'd been driving on for years. She wondered on a daily basis how she would kill herself that night.

That accident "fried" her, she told the Seattle Times this year. "I couldn't talk. The straw didn't break the camel's back; it gutted the sucker, left the camel for dead. I was numb, couldn't think. I was afraid of horses, hated riding."

Upon her return six weeks later, trainers didn't trust Krone and she gave them no reason to, either. She rode long-shot horses and lost handily. She continued having nightmares filled with horses' hooves. She grew more and more timid.

"Horses felt my anxiety, they got weird, they reared up," she has said. "I had been given a magical talent to positive-image a loser right into the winner's circle ... And then suddenly it was all gone, and I was exhausted." All Krone could think of was suicide.

One day at Saratoga in the summer of 1996, after another lousy day that included getting yelled at by a trainer, she bumped into a casual friend, Tom Qualters (a horse owner and frequent Saratoga visitor), who told her, "Well, there's tomorrow."

Krone said, "Well, there might not be any tomorrow."

Qualters, a psychiatrist, suggested she stop by his office, which she did the next night for a two-hour "emotional purge," Krone told Robert Lipsyte of the New York Times. "I felt full and empty at the same time, joyful and like I was peeling off my skin."

Previously, she had resisted any type of therapy. "I'm a jock," she has said. "I can do anything on my own. I thought it was humiliating to get help. Meanwhile, the only real relief I felt was planning my suicide. I saved sleeping pills, but I was going to drink alcohol, slit my wrists and maybe hang myself, too. I wanted to do one thing right."

Qualters diagnosed Krone with post-traumatic stress disorder and began seeing her four times a week. The pair visualized success for her and talked about issues from her childhood. Mostly, though, Qualters talked Krone through each painful experience, each new race -- and slowly, she began winning again. She never returned to her earlier form, but that was one of the mental barricades that she conquered, realizing that she was doing just fine at the level she was performing at.

Two years after meeting Qualters, she found a doctor in New Jersey who prescribed Zoloft. "When I started taking Zoloft, things got better. All the things I lost came back and I got to be myself again. It was a turning point in my career and life," Krone, who has a contract with Pfizer, the maker of the drug, told the Associated Press.

"I'm not sorry I didn't start the medicine sooner. I needed to first get to a place in talk therapy," she told the New York Times. "You don't fully realize how weird it was until you have yourself back. I'd been spending the minutes before a race using all my energy to defeat an anxiety attack, and now, well, listen to this. At the end of last year, in a 60-day period, my mother died, I got divorced and I moved to California. And I'm here, I'm OK."

When she finished second in the jockey standings in 1998 at Monmouth Park, N.J., Krone felt that she had beaten back her demons. "I wasn't the leading rider and I didn't have those multiple-win days, but the fear left me, the trauma left me and it was better," she told the New York Post. "I didn't even think about anything. I would get on horses that people said were wild, and they'd just melt in my hands, relax and do stuff they've never done before."

She retired April 18, 1999, after riding three winning horses and two seconds that day. Not too shabby.

Since retirement, she has worked as a horse-racing analyst for the Television Games Network, done some voice-overs for Nickelodeon ("Having a squeaky voice is paying off," she told the AP) and has taken some correspondence classes toward an undergraduate degree in psychology. She finished her high school degree in the late '90s. In January, she will begin work at Gulfstream Park as a spokeswoman for the track.

Her biggest achievement, though, was to become the first woman accepted into thoroughbred racing's Hall of Fame this year.

At her acceptance speech in August, she said, "I want this to be a lesson to all kids everywhere. If the stable gate is closed, climb the fence."

Shares