It's not every day that you find an FBI agent savoring the smell of a carton of bright green marijuana leaves. Nor is it easy to imagine a DEA officer impressed by the audacity and precision of a smuggler who slit his own thigh open, inserted 300 ecstasy pills and sewed it up himself. With most crimes, law enforcement agents don't share an aesthetic passion for contraband with the perpetrators they're trying to collar.

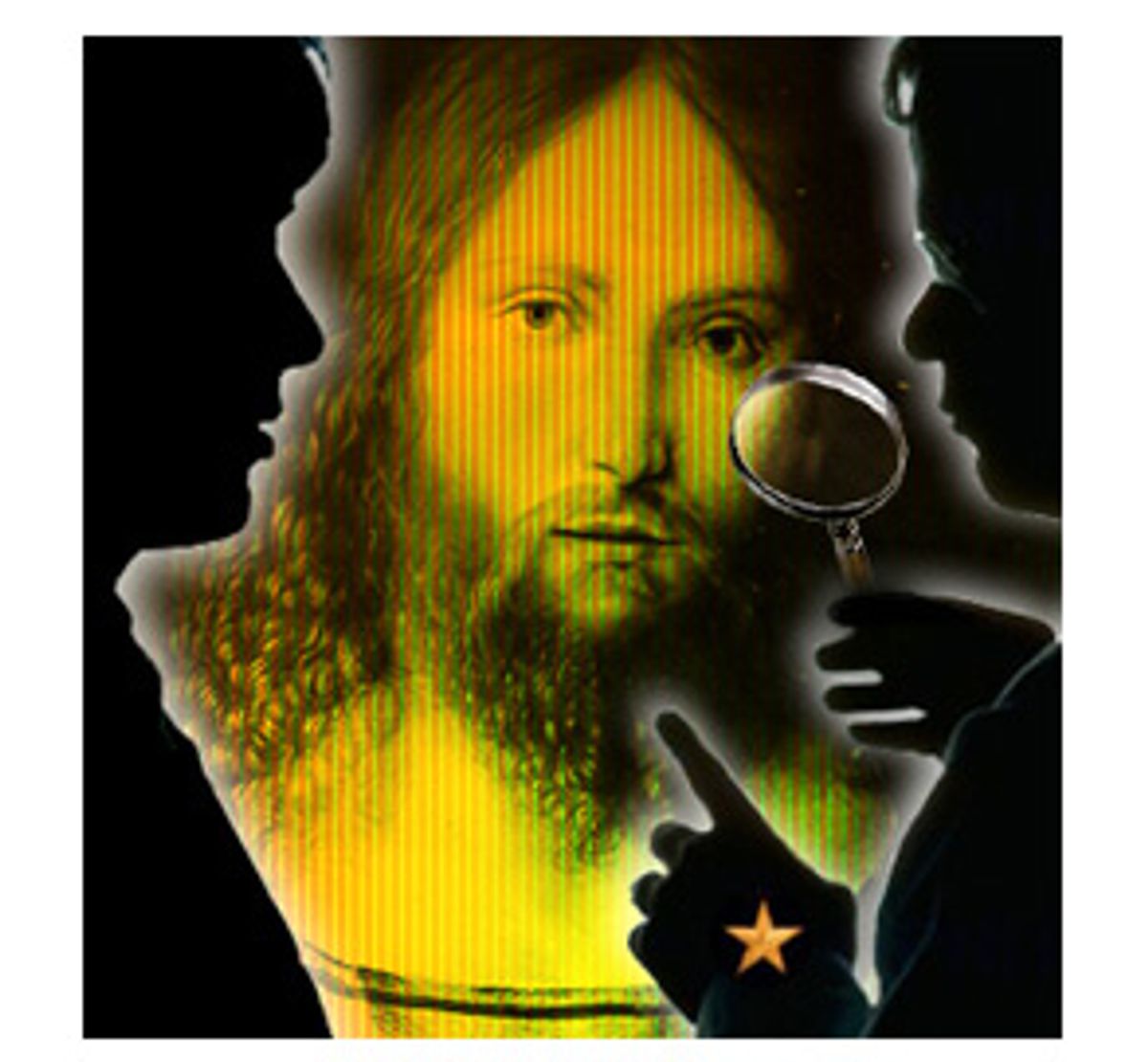

But in the world of art theft, such moments are commonplace. Take this month's seizure of the magnificent depiction of Christ by Venetian artist Jacopo de'Barbari -- a 16th century painting stolen from the Weimar Museum collection in Germany by American soldiers in 1945. "The suspect carefully described Christ's 'captivating' eyes in detail over the phone to me and I just couldn't wait to see it ... I couldn't stop reading everything ever written about the artist while I anticipated the seizure," says Joseph Webber, a special agent in charge at the U.S. Customs Service.

This slow-talking, cowboy boot-wearing, gun-carrying detective has been busting international criminals for 26 years. But as he begins to describe his role in recovering the Jacopo painting, his demeanor softens. "Have you seen the Jacopo painting?" he asks enthusiastically. "It is stunning. We made a copy and blew it up for our office."

At 6-foot-4, Webber greets me with a big, gentle smile. As he meticulously repeats his main points in a slight drawl, he comes across more like a politician than a James Bond -- oozing the simplest charm while speaking of the most complicated and highly sensitive matters.

"We're rural folk, my family," he says. "But I bring my toddlers to art and history museums every weekend. I love learning about art. I love figuring out puzzles, and art theft poses the greatest, most multileveled ones around." Webber handles all kinds of crimes, but has been one of the few at customs specializing in art theft cases over the last 10 years. He originally volunteered to work on those because he had fond memories of his college art history classes.

In the wake of the recent Jacopo recovery, Webber is taking art theft investigation to a new level. Beginning last week, Webber convened a unit of six agents who will undergo special training to handle such cases. Art theft seizures demand an ability to recognize valuable art, verify the authenticity of a piece and properly preserve it, and the job requires a masterful grasp of international regulations and the ability to work with people of astounding wealth and expertise. As in the case of the Jacopo piece, there are possibly hundreds of masterpieces hanging illicitly in living rooms or churches across the country.

"The first step is really raising awareness," Webber says. His unit has already launched the first "Most Wanted" list on the Customs Web site. Over the past few years, Webber has seized over $30 million worth of stolen art and artifacts -- in addition to making thousands of narcotics busts.

At first glance, Frank Vaccaro, owner of Master of Furniture in Baldwin, N.Y., and the man arrested in the Jacopo case, doesn't come across as an aesthete either. And certainly not someone who could spot a classic Renaissance painting out of a pile of posters and tacky frames. But he did: In 1998, a school art teacher, Sister Rose Mary Phol, brought the Jacopo painting to Vaccaro to have the frame restored. He noticed that the structure of the frame was anachronistic. He carefully removed a family photo that the nun had glued on top of Christ's portrait and began to research the painting. He returned the frame to Phol without the portrait, telling her he had thrown it away.

Meanwhile, Vaccaro had already contacted the Weimar Museum, determined that the painting had indeed been stolen in 1945 and proven in photos that he had it. He demanded a $100,000 finder's fee, and museum officials considered the request extortion. They called the U.S. Customs Service for help.

Enter Joseph Webber and Special Agent Bonnie Goldblatt.

Goldblatt went undercover as a Weimar representative and began to "negotiate" with Vaccaro. During recorded phone conversations, she obtained his address, a description of the painting and his demands. On Nov. 8, 1999, the agents had enough proof of ill intent, and obtained a search warrant. Agents found the small painting hidden in the ceiling of the furniture store. Vaccaro was arrested on the spot.

At the time, the museum estimated the painting's value between $150,000 and $400,000. It was subsequently appraised at $5 million, and because Vaccaro's demand was low in comparison to the actual value of the painting, charges were dropped. "I am happy the painting is back in the museum. That's what I wanted all along," he says. He just wanted a finder's fee as well.

And is that so wrong? After all, if it hadn't been for Vaccaro's astuteness, the portrait might never have been recovered at all. According to Chicago-based art theft attorney Thaddeus J. Stauber, while stolen property in general should be returned with or without reward, there is an even greater responsibility to return stolen art unconditionally. "Every piece of art is unique, there is only one, created in time. In that sense, art is irreplaceable. And therefore, there is a higher ethical demand to get it to its owner."

The good news is that "The Bust of Christ" did finally go back to Germany last week, just in time for Christmas -- and in immaculate condition. Of its mysterious half-century journey, investigators have only been able to piece together the following: In 1972, Msg. Thomas Campbell, pastor of the now-defunct St. John's Moda Christi RC Parish in Queens, N.Y., gave the painting to the school art teacher, Sister Rose Mary Phol. Campbell, now 85, has told Customs investigators that he can't recall how he came to be in possession of the painting, but he guesses that a parishioner may have given it to him.

Approximately 65 percent of all U.S. art imports arrive through the Port of New York, and in 2000 alone, the New York Office of Investigations seized $5.5 million in art fraud, accounting for 80 percent of Customs art seizures nationwide. The FBI is the other government agency that plays a leading role in recovering stolen art.

Robert Speil, a private investigator who spent 20 years investigating art-related crimes for the FBI, says there are no cases more fascinating than art theft. "For all crime, you get to work with eccentrics on both sides of the game, but in art investigations in particular, the people are more complex," says Speil, who also was turned on to art by his college art history courses. "The art experts are different from those who specialize in fur, for example. Art specialists are professors. I prefer working with them."

And the criminals are a unique bunch, too, he says. In one of Speil's favorite cases, a 35-year-old, drunk high school dropout shared Speil's fascination with this sort of refined, cerebral-minded crime. And the bond between the two men, at least according to the thief, was palpable.

Charles Richmond, a serial art thief, would lure gay men into private quarters -- Richmond says he, himself, is heterosexual -- steal their wallets and run. But he wasn't after their money. He wanted their I.D.s. He would then go to art galleries, study their collections at the library and return to initiate a sophisticated and ongoing dialogue with gallery staff. After weeks of softening them up, he would ask a question so challenging that the good-natured gallery attendant would leave the room to look up the answer. That's when Richmond would grab a painting and run -- but certainly not hide. He would typically scurry right next door to a neighboring gallery, stopping only to take one deep breath, and then calmly walk in. After showing his stolen I.D., he would sell the piece for about 10 percent of its value. He would cash the checks using the same I.D.

While Speil was searching for this quirky thief, Richmond was arrested twice for shoplifting. The first time, he had no fake I.D. with him so his real name was acquired and photographs and fingerprints were taken. The same week, he stole and sold a painting, posing as one of his gay victims, John Rogers. He was later busted for shoplifting again, and this time used Rogers' I.D.

The FBI's computer system noted the matching fingerprints, and Speil now had a face and name to go with. It was just a matter of alerting all the galleries in New York to his identity. Within six months, an attendant at a gallery on Madison Avenue called Speil, informing him that Richmond had just left the gallery. The FBI's headquarters at that time were four blocks away, and Speil and three other armed agents ran up and down Madison Avenue for about 40 minutes until they saw Richmond walk out of a different gallery, stolen painting in tow. They arrested him on the spot and within half an hour Richmond was "beaming with pride," confessing everything. He sent Speil Christmas cards from jail. "He sees us as players in the same game," says Speil. "And he thinks we all -- him included -- did a great job."

Richmond is out of prison and nowhere to be found this moment, according to Speil. "He began to think that the whole world, including the governor and I, were after him." When he got out of jail, Speil asked Richmond if he had any leads on any other illegal activity in the area, and apparently Richmond was alarmed by the line of questioning -- perhaps the insinuation was too artless for Richmond.

Vaccaro seems to have emerged from his foray into art crime in better condition, if a little overwhelmed. No matter how he tries to lose himself in his furniture store's holiday hustle, he knows that if he had played his cards just a little differently, he could have become somewhat of a hero in the history of art, rather than a perpetrator.

Shares