The anticipation surrounding "Traffic" is the sheer eagerness to see what Steven Soderbergh will do next. The critical acclaim that greeted "Out of Sight" and "The Limey" wasn't matched by popular acclaim until "Erin Brockovich" earlier this year. But that hat trick provided the kind of thrill that doesn't come often in movies, the thrill of accessible, intelligent, satisfying entertainment that is also genuinely exciting filmmaking.

So it's no fun to report that "Traffic" is something of a disappointment, albeit one that takes more chances than most directors' successes. The film is an Americanized version of a British TV miniseries, "Traffik," directed by Simon Moore for the U.K.'s Channel 4, and I don't think there's a scene in it that doesn't demonstrate Soderbergh's ambition or innovation. The failure is sadder because "Traffic" hums with the desire to make a good, meaty, provocative movie. Its shortcomings, however, can't diminish its one genuine thrill: the thrill of someone saying in a clear voice, "It's all bullshit."

The bullshit in this case is the government's ongoing war on drugs. "Traffic" comes at a time when there's evidence the public is beginning to doubt what politicians are telling it. The year-end issue of Rolling Stone reports that voters in California, Oregon, Utah, Colorado and Nevada approved measures that would allow the medicinal use of marijuana, allow nonviolent drug offenders to choose treatment instead of jail and restrict police from keeping seized property. (In one case, the government confiscated the life savings of a retired Oregon schoolteacher who unknowingly sold property to a man who used the land to grow pot; never accused, let alone convicted, the man never got back his money.)

And yet the majority of our politicians continue to claim that the war on drugs has already shown signs of success. Soderbergh doesn't dispute that. "Traffic" says that the war on drugs has been a roaring success -- for drug dealers. Soderbergh lays out how our policy of interdiction has been a boon for corruption and crime and how the lives endangered by drugs go far beyond drug users'.

"Traffic" tries to chart a course through the morass of blinkered good intentions, hypocrisy and lies that form the basis of our drug education and policy. The film intertwines four stories, from the highest levels in Washington, where a federal judge (Michael Douglas) is about to become the president's new drug czar while having to deal with the addiction of his daughter (Erika Christensen), to the streets of Tijuana, Mexico, where a local cop (Benicio Del Toro) tries to round up drug traffickers only to be caught in the tug of war between the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration and the corrupt Mexican army.

The film also tells the stories of two Los Angeles cops (Don Cheadle and Luis Guzman) working on turning a midlevel dealer (Miguel Ferrer) and of a woman (Catherine Zeta-Jones) who discovers that her husband (Steven Bauer) is a drug importer and slowly takes over the reins of his business.

The separation of the four stories (which somewhat overlap) bluntly articulates the film's thesis: that everyone, from the user to the most powerful dealer, from the lowliest street cop to the government's biggest drug honcho, is caught in the same cycle. "Traffic" makes its points very clearly and very cogently. It's hard to think of an argument for the drug war the film doesn't effectively counter. And some of its devices are chancy; at one point, Soderbergh puts lines about just how futile the war against drugs is into the mouth of a dealer. That's part of the movie's point, too. The dealer has the experience with drugs that people who inveigh against them most vocally lack.

But cogency isn't the same thing as forcefulness and, for all the guts and timeliness of the argument being made in "Traffic," in some essential way the movie never comes to life. Still, it's a small mercy that Soderbergh got hold of this subject before, say, Oliver Stone.

A touch of the inflammatory is exactly what the movie calls for but lacks. It's not enough for "Traffic" to tell us that the war on drugs is a sham; the movie needs to declaim it with fury and a streak of bitter humor. Soderbergh shows a trace of wickedness when Sens. Orrin Hatch, Barbara Boxer and Charles Grassley appear as themselves in a Washington party scene. Did they read the script? Did they have any idea they were appearing in a movie that exposes as a sham the government's bipartisan war on drugs?

There's something bracing about seeing public officials side by side with their hypocrisy. But reason isn't a substitute for drama or passion. "Traffic" should be scalding; instead it merely makes a solid argument.

Nothing in "Traffic" is as exciting as the astounding interview in the current issue of Playboy with New Mexico's Republican governor, Gary Johnson. Johnson provoked a huge ruckus, and the resignation of several of his cabinet members, when he came out forcefully for the legalization of drugs. His interview in Playboy is shocking; he speaks with the plain language that we simply don't expect from our elected officials anymore.

For Johnson, drug legalization has nothing to do with party politics, or with the fact that the drug war hasn't worked, that we substitute lies for honesty in our drug education, that the legalization of drugs would be a death blow to organized crime -- for him, these are simply givens. There's no handwringing about the people who might be attracted to drugs if they become legal; he's worried about the people being destroyed by the efforts to eradicate drugs now: junkies who run the risk of unclean needles and unregulated dope, people caught in the crossfire of high-crime zones, everyone who is denied services because of the drain on our economy from uselessly fighting drugs. But reading the interview you get the sense that, for Johnson, laying out facts that many people (and most of his political contemporaries) would prefer to ignore gives him a thrill and a sense of mission.

Part of the problem with "Traffic" is a structural one. The separate stories simply don't build to a crescendo. You have to find the tempo again each time the movie switches scenes instead of being carried along at the same tempo (which, for all its flaws, is exactly what happens in "Magnolia").

The problem isn't exactly a failure of craft. It's hard to fault Soderbergh for the way the film has been made. Even his most obvious bits of technique -- like using a different film stock, grainy and light-blasted, for the Tijuana scenes -- work without calling attention to themselves. Often his choices, like the way things swim out of focus when Christensen freebases, feel exactly right. The hand-held camera feels alert without ever becoming jerky or ostentatious.

And yet it's immediacy that the movie is lacking. Stephen Gaghan's script has an unfortunate tendency to sum up the point of a scene in a few key lines of dialogue instead of allowing us to discover the point for ourselves. And it's very hard for Soderbergh to keep up a sense of urgency when the scenes keep resolving themselves in topic sentences.

The acting is more variable than in Soderbergh's recent films. Cheadle and Guzman have a workaday likability, the familiar rhythms of two cops who have settled into the permanent state of being harried. Douglas, at first, seems to have been chosen merely because he has that conventionally handsome look of our younger elected officials. But he manages to show some passion in the scenes where he's trying to locate his daughter.

And as the daughter, Christensen (who bears an uncanny resemblance to Julia Stiles from some angles) is remarkable. She plays off the mess she's sinking into against the character's lack of worldliness, and she uses her look (like the baby fat still clinging to her cheeks) to suggest a girl who remains unformed. I wish that the script didn't provide her with such a conventional reason for the character's drug abuse (she's unable to cope with the pressure of being a straight-A student) or offer her a false, hopeful ending.

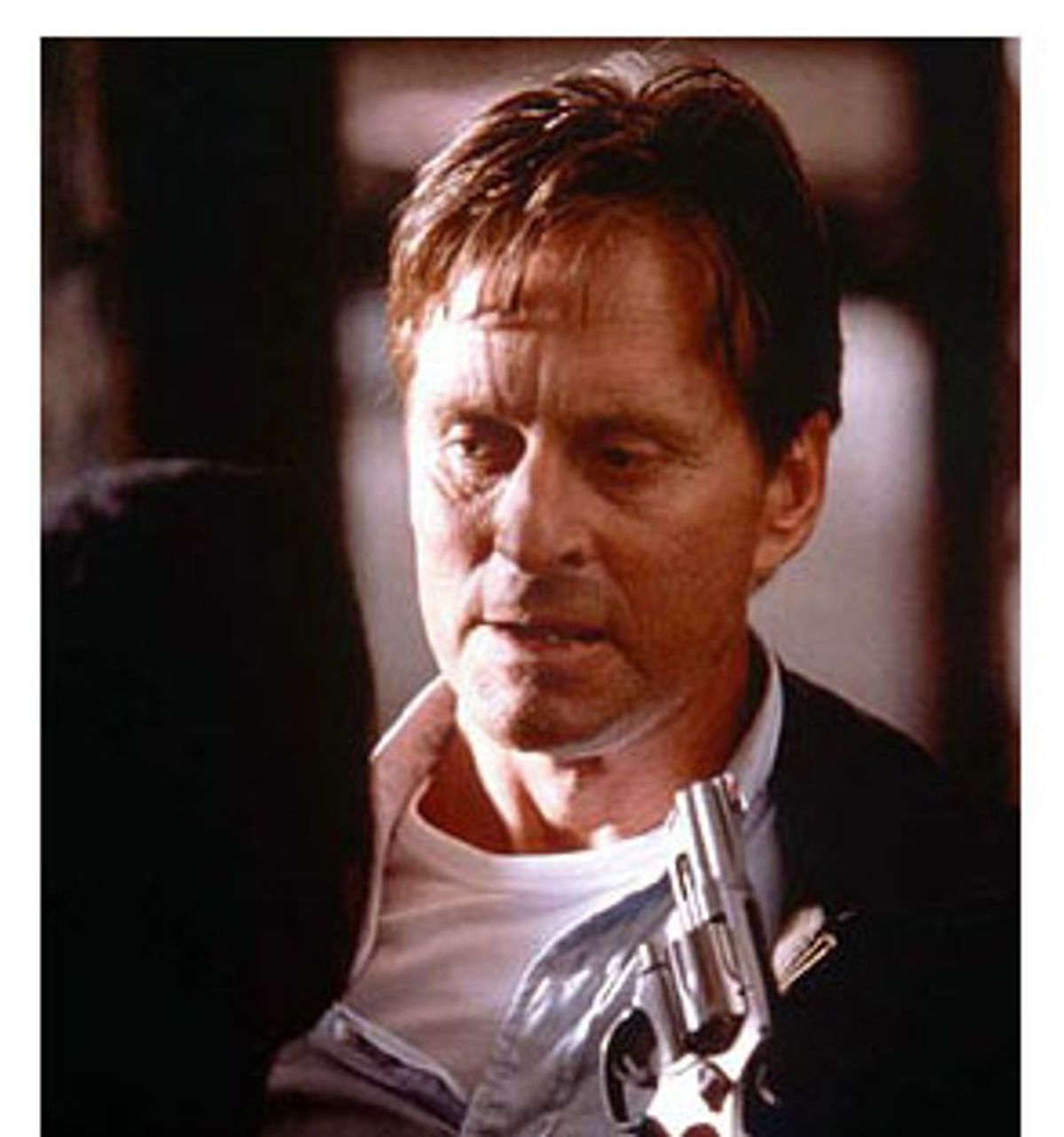

Best of all is Del Toro, with his perpetually sunken eyes. He has the kind of look that directors have heretofore used for crooks and crackpots. The stroke of casting him here is that his weary, unshaven countenance masks a straight-arrow hero, a guy who tries to come on as wised up, but desperately wants to believe that fair play and honor are still possible. And though the plot involving him is unfocused, the least well told of the four, Del Toro's portrayal of a growing sense of futility in a man with a strong belief in right and wrong carries it. In some ways it carries the whole movie. He's one of those rare actors who can make moral disillusionment seem attractive.

"Traffic" is a failure of a very high order -- a movie that takes a gutsy stand and displays real filmmaking savvy but simply isn't as exciting as it should be to watch. The best that can be said for it is that, in its best moments, it manages to display a canny ambiguity.

In the end the movie comes down to the smile of satisfaction on Cheadle's face as he pulls off a scam that will begin to turn the tables on a drug dealer no one has been able to nail. Cheadle's smile, that of the wiseass good guy who has put one over on the villain, is everything that action movies and thrillers have taught us to love. Soderbergh makes it seems like the foolish essence of our drug policy, the emblem of people not just doomed to repeat their mistakes, but willing.

Shares