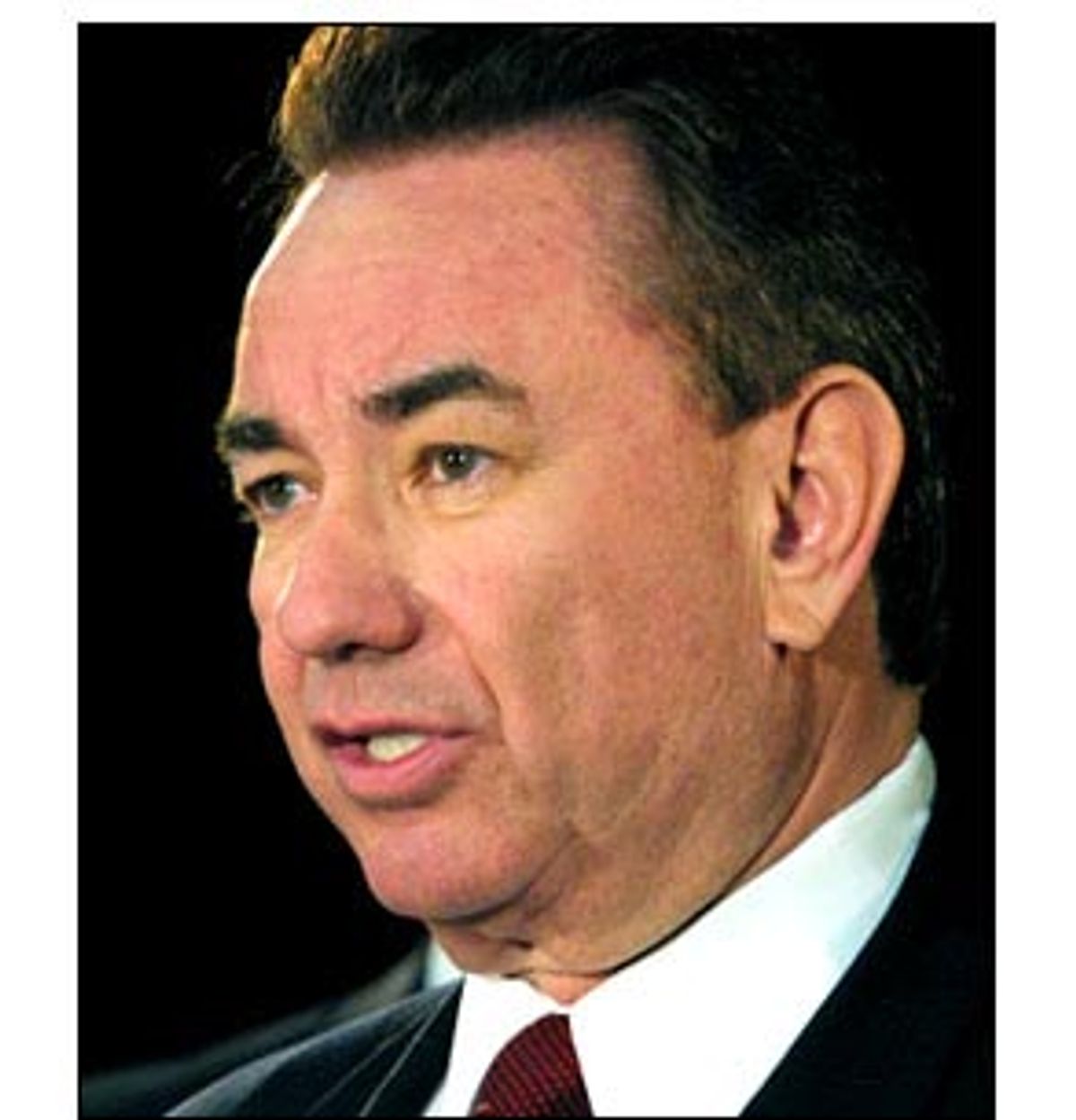

It's well known that Wisconsin Gov. Tommy Thompson, whom President-elect George W. Bush named as secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services on Friday, is opposed to abortion -- a fact that led Planned Parenthood to announce its opposition to his confirmation. Less well known, however, is that Thompson has strongly supported research into cells derived from human embryos -- research endorsed by President Clinton, but denounced by many anti-abortion groups and cautiously opposed by Bush. The looming showdown over embryonic cell research reveals just how complicated abortion and abortion-related issues can become when they collide with scientific research.

Just as President George Bush banned federal funding for research using fetal tissue (a ban Clinton quickly overturned), so right-to-lifers expect Bush to quickly reverse Clinton's endorsement of embryonic stem cell research. Bush has "consistently opposed federal funding for research that requires embryos to be discarded or destroyed," says his spokesman, Scott McClellan.

But banning funding for work involving embryos could be politically thorny. Embryonic stem cell research is particularly promising for diseases that plague seniors, like Parkinson's, and it has many Republican backers in the Senate and elsewhere. And at HHS, Thompson would be in charge of funding the research through the National Institutes of Health.

Thompson has a solid anti-abortion record, but in January 1999 he angered right-to-lifers in his home state when he invited University of Wisconsin biologist James Thomson to his state-of-the-state speech. Thompson introduced Thomson to the Legislature as a "bold pioneer" who is "leading Wisconsin into the next millennium." A few months earlier, Thomson had turned science on its ear by growing embryonic stem cells -- which have the potential to become any human tissue -- in a petri dish. The stem cells came from embryos donated by women at a campus fertility clinic. To get the stem cells, Thomson had had to destroy the embryos.

Although embryo destruction isn't the same as abortion -- the embryos were never implanted in a woman -- many right-to-lifers equate the two. At the time, Mary Matuska of Pro-Life Wisconsin blasted Gov. Thompson for endorsing research that "involves mutilating and destroying human embryos."

Despite her group's criticism, a Wisconsin university official says, Thompson has remained a steadfast supporter of Thomson's work. As governor, he spearheaded funding for several new biology buildings on the Madison campus, and a few weeks ago quietly helped quash legislation to ban fetal and stem cell research in Wisconsin.

All this has somewhat clouded Thompson's bona fides among cultural conservatives in his state. "The Wisconsin right-to-life folks are uneasy about Thompson," says Richard Doerflinger of the Pro-Life Activities secretariat of the U.S. Catholic Bishops Conference. Doerflinger says he's confident that regardless of his HHS choice, Bush will undo the federal guidelines, published in August, that enable funding for the research. "He has already said he disagreed with the [embryo research] guidelines, and we expect him to reverse them," Doerflinger says. "I'm pretty confident that's what he's going to do."

But the embryonic stem cells controversy is just one of a number of cutting-edge biomedical issues that don't cleave along traditional party lines. The use of genetic tests and distribution of private medical data, the screening of fetuses for a variety of genetic variations and the cloning of animals to make organs for transplant are all issues on the horizon in which Green neo-Luddites and the fundamentalist right may be warmer bedfellows than are Christian and libertarian conservatives.

Many biologists believe that Thomson's creation of an in vitro line of embryonic stem cells in 1998 opened breathtaking vistas in science and medicine. Hardcore abortion opponents, though, regard the microscopic embryos -- using what might be called the "Horton Hears a Who" rule -- as persons no matter how small, and just as worthy of protection as any fetus or born person, although they can legally be flushed down the toilet in most states.

Bush could scrap federally funded embryo research with a stroke of the pen, but McClellan wouldn't say if he's going to do that. Bush will "review executive orders, regulations and rules after he takes office," McClellan said, echoing the caution heard in earlier Bush camp statements on the issue.

Although the guidelines were published in August, an NIH board set up to review grant applications for embryonic stem cell research won't hold its first meeting until April. Robert Walker, a science policy advisor to the Bush campaign, says he doesn't think Bush has focused on the issue yet.

"I don't think it's a foregone conclusion what position he's going to take," agreed Dan Perry of the Alliance for Aging Research, a leading lobby for stem cell research. "I don't write off George Bush on this."

Neither does Doug Melton, a Harvard University embryologist and one of the few American scientists who has had a chance to tinker with the cells. Melton, whose work is privately funded, would like to try to use embryonic stem cells to make a human pancreas. He has a personal stake in it: His 8-year-old son has Type 1 diabetes.

"If Bush decides to retreat from the federal guidelines it will be a great disappointment to the scientific community. A lot of people spent a lot of time creating them very carefully," Melton says. "We hope that he spends at least as much time thinking about this as he does on death penalty cases, which from what I understand is maybe 10 or 12 minutes."

Embryonic stem cells are one of the hottest phenomena in biology. Biotech companies, which Republicans are eager to court, are excited about potential therapies growing out of stem cell research. Patient groups representing millions of voters are pushing hard for federal funding.

Although biotech companies such as Geron Corp. in Menlo Park, Calif., are funding some research with the cells, it's all secret. Many scientists feel that if done at all, such science should be publicly funded so the general populace can examine procedures and results. And it will take dozens (and perhaps hundreds) of labs working with the cells to get meaningful research in a short period. That can only happen with federal funding.

Christopher Reeve, who suffered a spinal cord injury in a 1995 riding accident, and Michael J. Fox, who has Parkinson's disease, were among the famous people trotted before the budget subcommittee of Sen. Arlen Specter, R-Pa., last year to demand NIH sponsorship of the research.

Senate leader Trent Lott, R-Miss., an opponent, promised to allow floor discussion and a vote on Specter's bill, but didn't deliver. An aide said Specter hasn't decided whether to reintroduce the bill this year.

The entities at the center of the controversy are the more than 150,000 embryos currently stored in liquid nitrogen at fertility clinics around the country, left there by parents who had their babies, or failed to get pregnant but moved on.

Each embryo contains several hundred cells of a primordial type that, when cultured, can be made to replicate eternally. The hope is that once scientists figure out how to manipulate them, the cells could be converted into any kind of human tissue, providing a virtual fountain of youth for cell cultures to replenish tissues damaged in anything from Lou Gehrig's disease to juvenile diabetes to Alzheimer's. In the nearer term, embryonic stem cells may provide valuable substrates for testing drugs and doing basic biology experiments.

"We need to make Bush understand this is potentially as big as space travel," Melton says. "He should think of the economic advantages. Cell replacement therapy could end up coming from companies outside of the U.S. because of restrictions he puts on research here."

Doerflinger and others have been quick to point out that there are potential alternatives to using embryonic stem cells to create transplant tissue. Other types of stem cells, generated from adult or fetal tissue, have shown some promise. Researchers, for example, have turned bone marrow stem cells into brain cells.

"There seems to be a great deal more plasticity in the human body than we imagined," says Ron McKay, a leading NIH stem cells researcher. But McKay and others still believe embryonic stem cells offer the most promise because they can be cultured relatively easily and grown indefinitely. And these scientists don't want any avenues of research shut off.

Shares