Ellen Reasonover found out the hard way that no good deed goes unpunished. When the St. Louis resident approached police with information she thought might help them catch the killer of a gas-station attendant, they arrested her instead, based on highly circumstantial evidence.

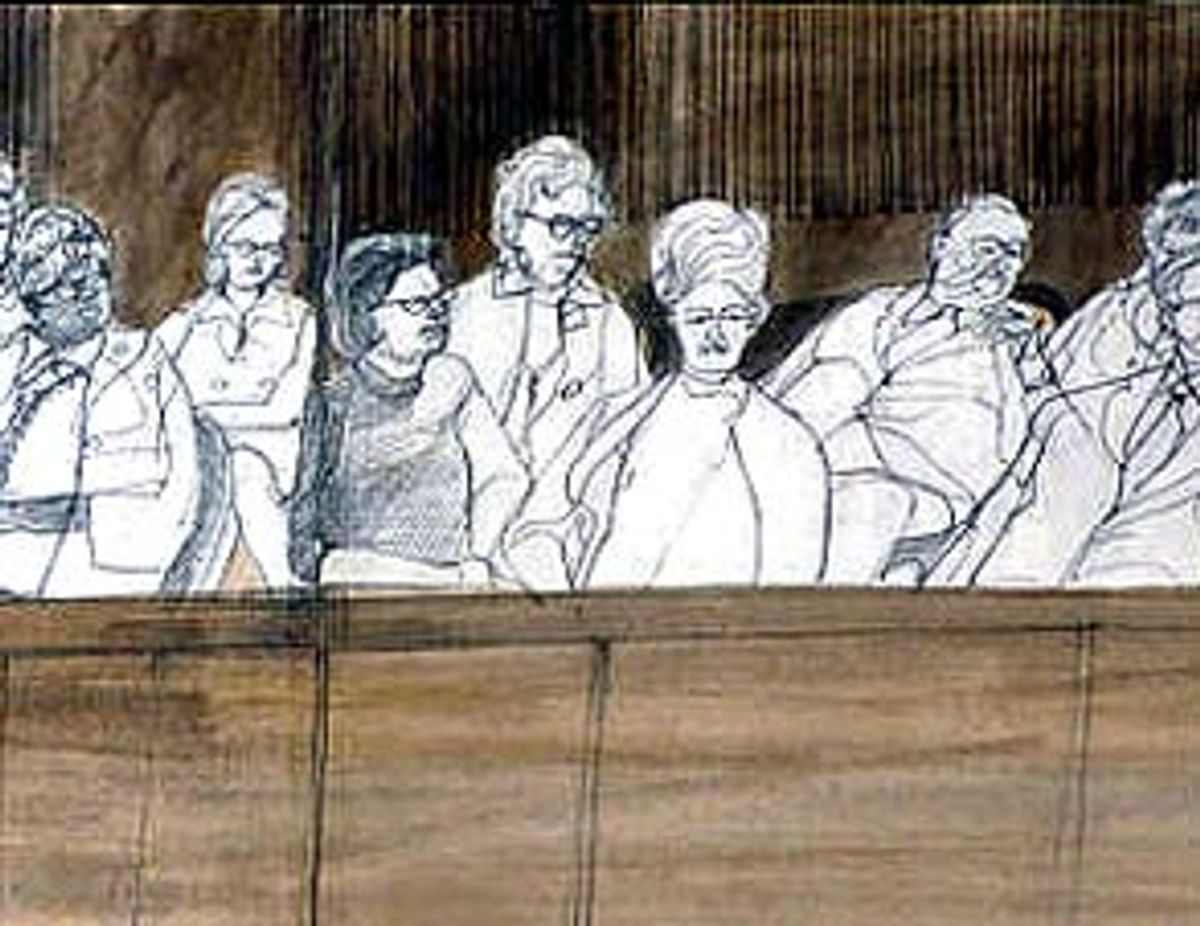

Constructing a case against her by relying on the testimony of two jailhouse snitches, the state sought the death penalty. An all-white jury convicted the young black woman, and all but one member of the panel voted to have her executed. Earlier this year, a federal judge threw out her conviction, ruling that the witnesses -- with the knowledge of the prosecutor -- had fabricated their testimony. So after serving 18 years in prison, Reasonover was released.

Reasonover's jury was ready and willing to believe the prosecutor's case at least partly because, as in all capital cases, the jury pool had been carefully, and legally, purged of anyone who had doubts about the death penalty -- a category that conveniently and disproportionately includes African-Americans and women. The very people many experts say are most likely to question prosecutors' arguments and hold to a presumption of innocence -- death-penalty opponents -- had been systematically kept out of the jury box.

A majority of Americans still back the death penalty, but polls have shown a steady erosion in support. A Gallup poll done in February, for example, indicated that 66 percent support it, down from 80 percent in 1984. Moreover, with growing numbers of people exonerated in the past few years after long prison stays, many people are apparently also losing confidence in the integrity and fairness with which it is administered.

The fairness issue became a leitmotif in the presidential campaign. Although both presidential candidates said they supported capital punishment, the media focused on Bush's record of presiding over more executions than any previous Texas governor, including 40 just this year, and on the apparent inequities in the state's judicial system. During the second debate, Bush seemed to grin when discussing the death penalty -- an action that prompted a pointed question from a member of the audience during the third and last debate.

The questions about capital punishment have prompted some states to take some precautionary steps. In Illinois, where more than a dozen death-row inmates have been proven innocent since 1977, the Republican governor, George Ryan, announced a moratorium earlier this year. Other states are studying the issue and facing growing calls for similar moratoria and for automatic access by condemned convicts to DNA testing, which in some cases has conclusively exonerated inmates.

Yet despite this new concern, a major and controversial element of the system is being largely ignored: the right of prosecutors and judges to eliminate, "for cause," any potential jurors who say they might not be willing or able to vote for death during the penalty phase of a murder trial.

Whatever one might think about the death penalty itself, the trouble with screening out death-penalty skeptics -- a process known as "death-qualifying" the jury -- is that it does a lot more than simply eliminate jurors opposed to capital punishment. It makes for juries that tend to be white, male and significantly more likely to convict the person accused of the crime in the first place. In a 1968 landmark study, Hans Zeisel, a law professor at the University of California at Berkeley, found that death-qualifying juries led to an 80 percent increase in the conviction rate.

"When you excuse all the people who are opposed to the death penalty, it's a kind of law-and-order screening device," says Craig Haney, a professor of psychology and sociology at the University of California at Santa Cruz who has been polling jurors and studying jury selection for 35 years. "You end up with a group of people who evaluate evidence a little differently, who are more likely to find evidence to be incriminating, and who generally don't even understand or accept the concept of presumption of innocence."

But proponents of death-qualifying say that if there were no such procedure, nearly every jury would likely include one or more members who would veto any death-penalty conviction, essentially rendering void the capital punishment statutes of 31 states and the federal judicial system. Moreover, they add, defense attorneys get to excuse any potential juror who publicly admits to an inflexible intent to impose death on anyone convicted of murder, regardless of mitigating circumstances or the instructions of a judge.

But defense attorneys counter that since not many potential jurors are willing to state such a position so bluntly, few actually get excluded on those grounds. And they stress that the effects of death-qualification on the racial composition of juries can be quite stark.

In a 1994 study, for example, Haney and coauthors Aida Hurtado and Luis Vega reported that while minorities accounted for 18.5 percent of the people in the California jury pools they examined, they represented 26.3 percent of those excluded from jury panels through the death-qualifying process.

A North Carolina jury study conducted in 1982 found an even greater disparity, with 55.2 percent of black potential jurors being excluded during the death-penalty qualifying process in contrast to 20.7 percent of whites. Studies also indicate that women tend to be excluded, since they are also more likely to oppose the death penalty.

The net effect is that -- despite Supreme Court rulings that excluding jurors because of race is grounds for a mistrial -- prosecutors can achieve much the same result without specifically using race as the criterion. "Death-qualifying a jury basically eliminates half of the potential black jurors," agrees David Bruck, a South Carolina defense attorney who specializes in death-penalty cases. "It's quite an ethnic cleansing that goes on and it is very disturbing."

The right to excuse jurors for cause is important because both sides in a criminal case are granted only a limited number of so-called "peremptory challenges," which allow them to dismiss potential jurors without having to offer any reason at all.

Prosecutors know that death-qualifying a jury is a great way to help ensure a conviction. That, say experts, is one reason why many of them -- particularly in jurisdictions with high death-penalty rates like Texas, Florida, Illinois, Virginia, California and Pennsylvania -- deliberately overcharge in murder cases even where they know the death penalty is not appropriate or likely.

In other words, the process can lead to higher conviction rates -- and most likely to more wrongful convictions -- not just in capital cases, but in other murder cases, too.

In Philadelphia, District Attorney Lynne Abraham seeks the death penalty from the outset in an astonishing 85 percent of murder cases, according to a study from the city's public defender's office. One reason for the Philadelphia district attorney's predilection for capital cases may be a jury selection training tape prepared in the mid-1980s by then Assistant District Attorney Jack McMahon.

In that tape, which is featured in the appeal by black journalist Mumia Abu-Jamal of his 1982 death sentence for the killing of a white Philadelphia cop, McMahon urges prosecutors to seek to impose the death penalty in as many cases as possible. That way, he explains helpfully, they then get the benefit of death-qualifying jurors, and with their peremptory challenges they can remove even those who express vague or minor concerns about imposing the ultimate sanction.

Abraham's office did not return repeated phone calls seeking comment.

Ironically, McMahon, now in private practice, has become a vocal critic of the very practice he once championed. "The reason district attorneys like Abraham so frequently seek the death penalty is that they get a conviction-prone jury," says McMahon, who now defends clients in capital cases. "Now they'll all tell you they don't do that, but they're full of crap and they know it. No one who's been working in this business would say that if they were honest. The whole process of death-qualification is terribly unfair."

McMahon insists that he hasn't had a change of heart. "I've always known this to be true," he explains. "But when you're a prosecutor you do what works to your advantage as a prosecutor. It's permissible, so you take advantage of it. But I will say that now that I'm on the defense side, I can see what a handicap it is for the defense."

In Abu-Jamal's 1982 murder trial in Philadelphia, the jury pool was in fact gutted of blacks during the death-penalty screening conducted by prosecutor Joseph McGill, despite objections raised by the defendant's attorney. In a city that is almost 44 percent black, the former Black Panther ended up with a single African-American on the jury that convicted him and sentenced him to death. In addition to screening out more than 20 black jurors through the death-qualification process, McGill used his peremptory challenges to eliminate another 11 black potential jurors who hadn't expressed any particular concern about the death penalty.

The National Association of Attorneys General takes no position on the issue of the fairness of death-penalty qualifying of juries.

But one academic expert who does defend jury qualifying in death-penalty cases is Paul Cassell, a law professor at the University of Utah College of Law and a former federal prosecutor. A death-penalty advocate who served as an attorney for the families of victims of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, Cassell questions the accuracy and significance of the jury attitudinal surveys cited to challenge death-qualifying.

"I am not sure that juror attitudes carry over into the convicting or sentencing of people," he says. While conceding that he is not aware of any studies refuting the claim that death-qualified juries are more conviction-prone, he insists that the argument remains unproved.

Meanwhile, critics of death-penalty qualifying say the problem is not just that the impaneled jurors are more inclined to listen to prosecutors. The very process of death-qualifying, they say, can bias potential jurors against the defendant.

Consider this. In any other criminal trial, whether it's petty larceny, assault with a firearm or attempted murder or rape, attorneys are expressly barred from discussing possible penalties before or during the trial. The reason: Courts have long felt that discussing the penalty could encourage the jurors to start assuming that the defendant is somehow guilty.

"Yet in death-penalty cases, where the issue of guilt or innocence is most crucial, we go ahead and discuss the ultimate penalty every time before the trial," says Santa Cruz psychology professor Haney.

We all laugh when the Queen of Hearts in "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland" says, "Sentence first -- verdict afterwards." But in this country's capital trials, that's basically what's going on.

The qualification process itself can become extremely contorted and bizarre. Once potential jurors have expressed opposition to the death penalty, the defense attorney -- seeking to salvage that person for the panel or at least force the prosecutor to use up a peremptory challenge -- often postulates particularly heinous murder scenarios so they will concede that under some extreme circumstances they might indeed consider voting for death.

Take Betty Brown. The 67-year-old black Philadelphia woman was thrown off the panel of prospective jurors in the Abu-Jamal trial after she said she opposed the death penalty. Trying to keep her on the jury panel, a defense attorney asked how she would feel about the death penalty if one of her two sons had been murdered. "'I don't even like to think about something like that happening to my boys,'" she recalls saying. "But I told the judge, 'Killing a murderer wouldn't bring back my son'"

Brown says she thinks it is "simply wrong" for people like her to be excluded from juries for their beliefs. But given her firm opposition to the death penalty, might she have been unable to find the defendant in that capital case guilty? "No, no," she says flatly. "If he's guilty, he's guilty, and I'd say it. And I was willing to serve."

While many potential jurors are kept off panels because of their anti-death-penalty beliefs, Haney reports that some impaneled jurors who are squeamish about imposing the death penalty can end up having their earlier comments thrown back at them during the penalty deliberations.

"A lot of jurors we've interviewed after trials have told us when they'd object to death other jurors would tell them, 'You promised the judge that you'd be willing to impose the death penalty,'" says Haney. "The hypothetical argument that they could conceivably impose death in some particular situation is later treated like a pledge to do it."

Given the inherent problems in death-qualifying juries, why has there been so much focus on possible moratoriums, DNA testing, poor defense lawyering and other factors and so little concern expressed about the very fairness of the jury-selection process?

Probably the main reason is that the Supreme Court has already ruled the matter -- in favor of the prosecution. Before 1968, it was routine for all those opposed to the death penalty to be excluded from juries in capital cases. That year, in Witherspoon vs. Illinois, which dealt specifically with the process of vetting potential jurors for their death-penalty views, the Supreme Court imposed strict limits on how easily they could be excluded.

After hearing about the higher conviction rates found in the Berkeley study and other research, it ruled that only those who absolutely, under no imaginable circumstances, could ever vote for death, could be excluded. The court held that by excluding all death penalty opponents the state had "crossed the line of neutrality" and created "a tribunal organized to return a verdict of death."

But in 1986, a reconstituted high court under Chief Justice William Rehnquist broadened the permissible grounds for excluding jurors. In Wainwright vs. Witt, the court basically granted prosecutors free rein to excuse any potential juror who expressed any qualms at all about imposing the death penalty, since that would "impair the performance of his duties as a juror in accordance with his instructions and his oath." Under this standard, salvaging a juror through "witherspooning" -- getting death-penalty opponents to acknowledge that under particularly heinous circumstances they would vote for death -- has become much tougher.

The high court also made state courts the final arbiters of the fairness of jury selection, making it extremely difficult to obtain federal review of convictions on jury-selection grounds.

"The problem is that once the Supreme Court decides something, Americans have a tendency to assume that it means it is a good thing, not just an allowable thing, so they just stop thinking about it," says South Carolina attorney Bruck. "But in this case, the court didn't say it was a good thing, just that they'd allow it unless more studies came along to show it was a really serious problem."

A major difficulty in addressing the issue is that -- short of eliminating the death penalty -- there's no easy fix. And though some members of Congress would like to reform the death-penalty system at the federal level, a Bush presidency does not augur well for change.

Neither does the composition of the Supreme Court. Even if the courts found the practice to be unconstitutional because it ends up biasing a jury, it could cause monumental nightmares by potentially opening up the door to a new trial for nearly every one of the 3,600 inmates on death row -- not to mention many more who, like Reasonover, received less than capital sentences but were judged by a death-qualified jury.

Nor is simply allowing defendants' attorneys the unfettered right to dismiss death-penalty proponents the answer. Assuming we maintain the death penalty, as is clearly the popular inclination at the moment, that approach would make it difficult to impanel jurors who would convict in capital cases -- a politically untenable solution in death-penalty states.

Some have suggested using unscreened jurors for the guilt phase of a trial and then screening and seating a new panel for the penalty phase. But the new pro-death-penalty jurors would have heard none of the nuances of the trial evidence and would clearly be prejudiced against a defendant already found guilty of the crime.

A modified reform being proposed by some critics, including Haney and Bruck, is to wait until the penalty phase of a trial to death-qualify the jurors; those expressing strong objections to the death penalty could be replaced with alternate jurors who had attended the entire trial. But in order to have enough alternates on hand, there would have to be many more of them than usual to avoid the chance of a mistrial. Given the difficulty courts are already having filling jury boxes, this would be a major challenge.

A third possibility suggested by death-penalty advocate Cassell would be to grant the judge the authority to impose the sentence without a jury's direction, as happens in Colorado and Arizona. But for the most part both sides oppose such a move -- prosecutors because it deprives them of the benefits of death-qualifying, and defenders because they generally would rather bet on convincing at least one juror to vote against death than on having to convince a judge.

The public's opposition to the death penalty is not likely to increase dramatically anytime soon. So unless new studies prove that qualifying juries is so discriminatory that even the current conservative Supreme Court feels compelled to reexamine the issue, we're stuck with a process that is clearly flawed -- and flawed in a way many experts agree increases the likelihood of mistaken convictions and executions.

"Nowadays more people believe in the death penalty, so I don't think there's much chance there will be a change in the way we pick death-penalty case juries," says Haney. "But my philosophy is that you have to keep collecting the data and making the case until some court is willing to look at it again and do something about it."

Shares