Is Elsa Bauml really crying over a lost nose hair clipper?

It looks that way. Sitting in her Upper West Side office, Bauml, who has been selling nose hair clippers for half a century, can't stop the tears as she discusses the imminent demise of America's original and best nose hair clipper, the Klipette.

This week, the Hollis Co., maker of the Klipette -- and little else -- for those 50 years, will close. The Klipette will be no more.

"This is a very emotional time for me," says the 85-year-old Bauml, who has single-handedly run the company since her husband's death in the early 1970s.

"Klipette was my husband's baby. All my customers have been calling and writing, saying that a part of them is dying with Klipette. It's all very sad. I told my son that I don't want to be here the day he cleans out the office."

All this for a nose hair clipper?

No, not just any nose hair clipper but the Klipette, arguably the most important innovation in men's grooming since the comb. You may not know the product by name, but you've seen one, probably in an uncle's medicine cabinet or on your father's nightstand.

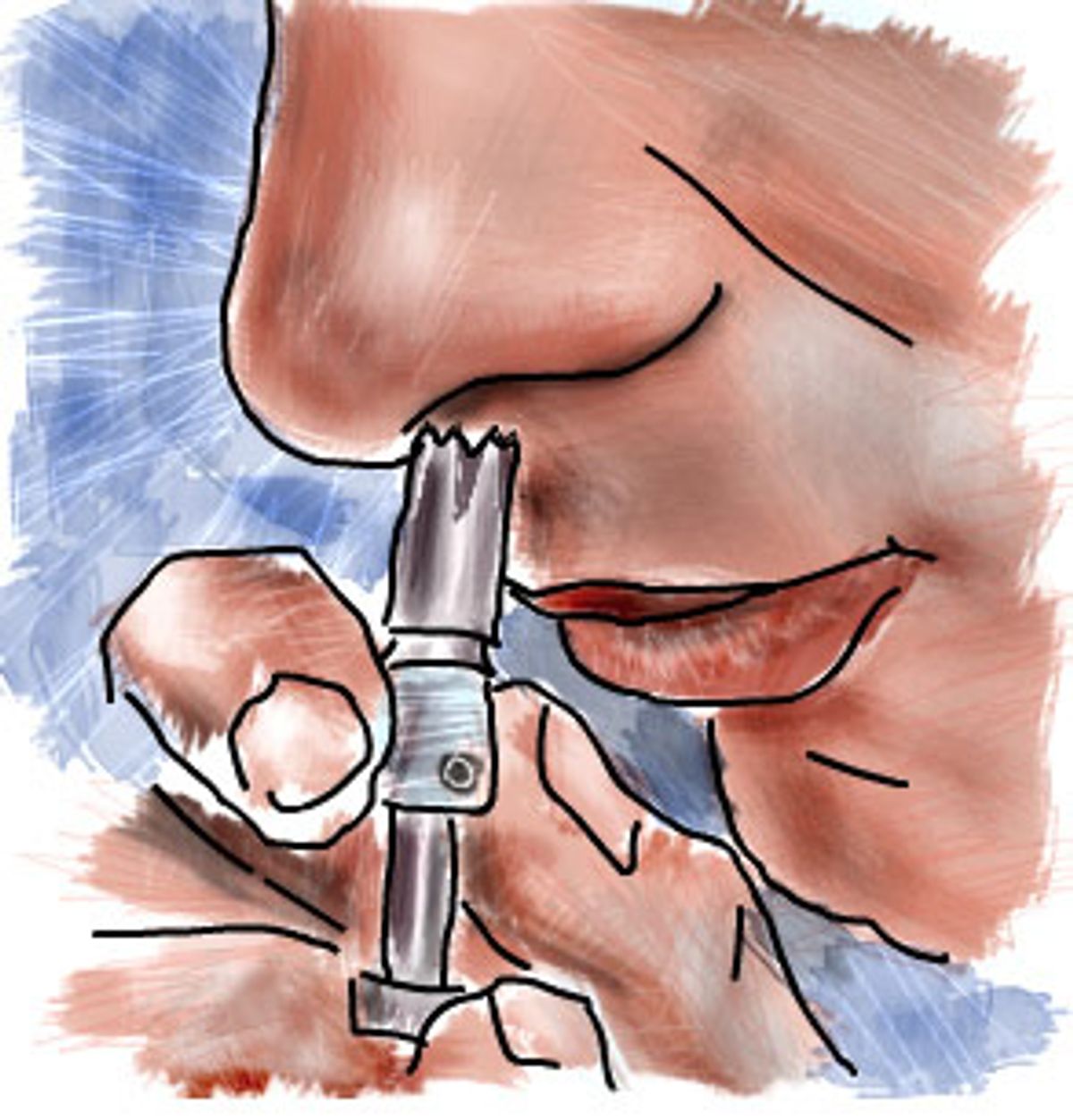

The Klipette is unmistakable: This unique contraption, which looks like a drill bit, consists of two concentric carbon steel cylinders held together by a simple screw. Hold it inside your nostril and turn the bottom, and voilà, nose hairs disappear without discomfort.

It is simplicity, it is precision, it is perfection itself.

If you haven't seen a Klipette, you've definitely seen the ads for them, all featuring a smiling man sticking a Klipette up his nose. ("So easy and safe!" the ad reads. "No pulling, no irritation, no infection.")

Before the invention of the Klipette, men had to either go to a barber or guide a pair of scissors up their nose with one hand and snip with the other. The former was an unnecessary expense while the latter was messy, imprecise and undignified. The Klipette revolutionized this chore, and took care of ear hair to boot.

Yet there's something bigger at work here, something more important than a mere nose hair clipper, something that explains Elsa Bauml's tears. The story of how a quirky tool was invented in a garage in New Jersey and then built into an international icon of hygiene is nothing less than the story of America itself, condensed down into those two nostril-width cylinders of hair-clipping steel.

Adolf Hitler set the story in motion.

Anton Bauml and his future wife escaped from Germany to America in 1938. But they were no common refugees. Elsa's relatives included two knights of the British Empire and an uncle named Henry Morgenthau Jr., who just happened to be the secretary of the Treasury at the time.

Anton's family was no less prosperous, having owned a bookstore where composer Richard Wagner shopped (and sometimes didn't pay his bills). In fact, the great anti-Semite once showed up at the Bauml store with his German shepherd and his cane and slapped Anton across the face after he got into a fight with Wagner's son, Siegfried.

"I'm just giving you back what you gave my son," Wagner told him.

But coming to America meant closing the doors on the Old World, the Wagner stories and the knighthoods -- things that meant nothing in America. Besides, America would open other doors.

Elsa was working as a masseuse in New York when a customer told her about the Klipette, which had been invented a few years earlier by a Mr. Clark in New Jersey. The naked man on the massage table had bought the company from Clark and now wanted to sell. Would Anton Bauml be interested?

Would he! Not only was Anton's business failing, but he was so broke that in a low moment he'd sold a letter that Wagner had written to his father -- a family heirloom in which the composer apologized for not paying a bill -- to the New York Public Library for $25.

"We took a chance," Elsa said. "We didn't have any money, so he sold us the company for $1,200 -- $100 a month for a year. I think he wanted to do a mitzvah [a nice thing] for two poor refugees."

For Anton, owning the company that made the Klipette was more than just a business venture. "My husband was a well-groomed man," Elsa says. "He always resented that the barber would have to clip his nose hair. He thought this was a great product because people could do it at home cheaply and safely."

Although the Klipette had been around for a few years, it had failed to capture the vast market in postwar America for a safe, reliable nose hair grooming tool.

The Baumls changed that, taking out ads in magazines such as National Geographic and Parade, which always featured a smiling man and the warning "Don't pull hair from nose, [it] may cause fatal infection." Later, Elsa Bauml expanded the company by selling the Klipette wholesale to barbershop supply outfits.

Millions were sold. Billions of nose hairs were safely clipped.

"It was a revolutionary product," says Arthur Marks, owner of Cutiecut, a distributor of beauty products. ("If it's a scissors, I sell it.") "Klipette was the first and the best."

The Klipette was alone in noses for decades, quietly going about its business of making men appear civilized. When competitors finally arrived, they were knockoffs of the most shameless kind. One, a black plastic model called Groom Mate, went so far as to copy the Klipette's revolutionary cylinder-within-a-cylinder design.

"Naturally we looked to Klipette for inspiration," admits Mark Bellm, vice president of PHR Systems, which started making the Groom Mate in 1989. "First we checked to see if they had a patent -- it had expired -- so we, uh, used their principle."

Bellm realized that this country was big enough for two nose hair clippers. He now sells his product for $8.95 -- "including postage and handling," he says. (The latter prompted my question: "For the love of God, what is handling?" Bellm paused for a second and gave an honest answer: "You know, I don't really know what handling is.")

Bellm claims his product is better than the Klipette, but Elsa Bauml knows a cheap copy when she sees it.

"He stole our design and thinks he's better," Bauml said the other day, tearing up again.

But she's not crying over her competitors. As she holds up a Klipette for the last time, she is not holding a mere grooming device, but the physical embodiment of her life in America, a symbolic totem of one great American family's journey from the prosperity of Old World gentility to the bootstrap prosperity of New World gumption.

She is not just crying over a lost nose hair clipper.

"Now, it's all gone," she says.

Shares