Sean Penn's work as a director is intelligent and considered. He appears to be probing for the psychic truth of each moment, and he reveres actors, allowing them the space to explore and ruminate on their characters. When so many movies are slovenly and dumb, the type of care that Penn takes is not inconsiderable.

But he is also the furthest imaginable thing from an instinctive filmmaker. Unlike his acting, Penn's direction is given to flat, self-conscious realism. He has no feel for pacing, no cunning, no natural flow. The stray shots -- of the hoods of dirty pickup trucks, a ticking clock, a slot machine's whirring -- and the stray actors' moments accumulate without cohering into a larger vision. Penn's movies, including the new "The Pledge," the third he has directed, play like what you might see in an acting and directing workshop, the tentative, exploratory work done before a performance, before settling on a tone or an arc that will carry the audience through the story.

Some directors are geniuses at employing improvisation techniques within an established structure (no one is better than Robert Altman), but Penn doesn't have the imagination or the discipline to pull it off. You wish him well because he so clearly wants to do meaty, worthwhile work. I winced at the laughter that punctuated the preview screening I attended, but "The Pledge" is so maddeningly unsatisfying that I understood exactly why the audience threw up their hands in exasperation at the end.

It makes sense that Penn would be drawn to Friedrich Dürrenmatt's detective novella "The Pledge"; it's a sort of anti-thriller that suits his anti-movie tendencies. The story is told within a framing device that's jettisoned from the film. After delivering a lecture on his craft, a mystery writer meets a police detective who tells him a story to illustrate how, in real life, crimes aren't solved as conveniently as they are in crime fiction. It's a compact and compelling book, and its portrait of an obsessed cop has moments of real creepiness.

It's also a cheat. When writers or directors hook an audience with the conventions of a genre and then, perversely, refuse to make good on that promise, as Dürrenmatt does, they're in effect saying, "I'm above this sort of thing," and it's the readers and moviegoers who end up feeling cheated, made to pay the price for the creator's show of higher taste. Dürrenmatt's book is a brilliant piece of literary dissection, an attempt to deconstruct the conventions of the detective genre by placing them alongside the unresolved messiness of real crime. But it's also neither low enough nor high enough to be satisfying.

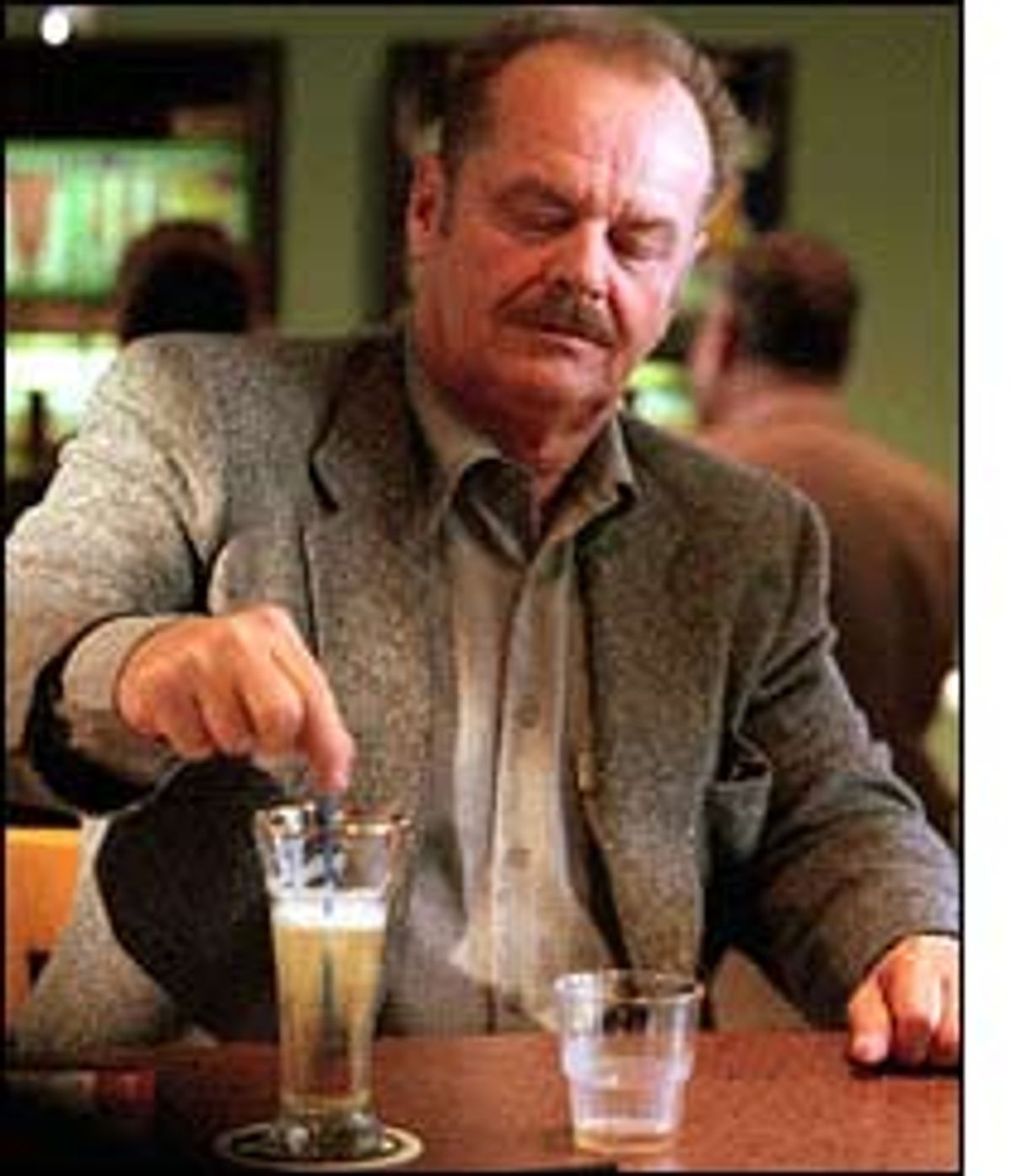

Penn and screenwriters Jerzy Kromolowski and Mary Olsen-Kromolowski have moved the story to modern-day Reno, Nev. Jack Nicholson plays Jerry Black, a police detective who, a few hours before he's set to retire, gets word that a little girl has been brutally murdered in a rural community. An eyewitness has seen an Indian man (Benicio Del Toro) fleeing from the murder scene. When it turns out that the fellow has a previous conviction for statutory rape, he appears to be the obvious suspect. It's too obvious for Jerry. Captured, the Indian readily accedes to the confession Jerry's designated successor (Aaron Eckhart) suggests to him. But to Jerry it's clear that the man, who's mentally handicapped, doesn't know what he's doing. And when he kills himself in police custody, Jerry is the only one unwilling to close the case. Dogged by the promise he made to the dead girl's mother (Patricia Clarkson), Jerry begins investigating on his own time, becoming increasingly disheveled, and without help from his former colleagues, he thinks he's cracking up.

His obsession begins to kick into high gear when he learns of two similar unsolved murders of little girls and he's able to deduce the parameters of the area the killer is prowling. He buys a gas station in the rural town and, relying on cryptic clues left behind in a drawing done by the most recent victim, spends his days watching his customers, certain that the killer will reveal himself. After befriending a young, divorced waitress, Lori (Robin Wright Penn), who's being threatened and beaten by her ex-husband, Jerry invites her and her little girl, Chrissy (bright, clear-eyed Pauline Roberts), to live with him; and the three form a sort of surrogate family.

The warmth that Penn introduces into the couple's relationship, and the love affair between them, may seem like a softening of the quid pro quo relationship that exists between the woman and the detective in Dürrenmatt's book. But it has the potential to make what follows seem even more disturbing. When Chrissy confides in Jerry that she's met the mysterious man he's seeking ("the wizard," she calls him), he uses the child as bait to catch the killer.

Nothing that follows happens in the way we're led to expect, but Penn isn't enough of a craftsman -- or an entertainer -- to make use of the misdirection. So, like Dürrenmatt's, his version of the material winds up failing as both thriller and character study. Some of what he comes up with is striking, like the opening shots of a round-the-bend Nicholson, over which Penn superimposes a shot of black crows; for a minute, it looks as if Jerry has been visited by the torments you see in Vincent van Gogh's final canvases. There's also an effective moment when a young, overweight boy discovers the body of the murdered girl and registers the shock by his wheezing inability to catch his breath. And there's a lovely view of Penn after she first kisses Nicholson where her smile registers in a shot that allows us to see only her eyes.

But too much is calculated -- Jerry's fragile mental state signaled by an ominous, amplified close-up of a ticking clock, the repeated quick cutting to stray objects that loom up with portentous meaning -- or calculatedly odd. A police receptionist painting her toenails is shot so we see her fat haunches. And is there a reason why several of the townspeople appear to be (or are played as if they were) retarded? Penn's periodic attempts to jack up the thriller tension are hokey. He may be trying to avoid the impersonal violence of thrillers, but he miscalculates badly in showing crime scene and autopsy photos of murdered children.

Penn has assembled an amazing cast -- Sam Shepard, Harry Dean Stanton, Vanessa Redgrave and Helen Mirren all turn up. Most have only a scene, and some, like Mirren and Redgrave, use their authority to make an impression. But you want more from them than service roles. And as much as he loves actors, Penn doesn't know when to say no to them. Del Toro, so good in "Traffic," gives a gimmicky performance as the mentally handicapped Indian accused of murdering the little girl. Alternately mumbling, employing a strangled Marvin the Martian voice or panting like a dog, Del Toro makes the kind of bad choice that an alert director would have overruled in rehearsal. It's an actor showing off, and throwing you right out of what should be a key scene.

The best of all the cameos is from Mickey Rourke, as the father of a girl who has disappeared. He looks like hell, puffy and gray, but in his few minutes of screen time he banishes from your mind all the tabloid stories of his hard living. Rourke gets to the naked essence of a man unhinged by sorrow. In a way, the brevity of his role is a favor; I don't know how he could sustain the depth of grief in this scene over a longer performance.

Nicholson gives in to neither the clowning showiness nor the heavy-spirited recessiveness he is prone to. Were the film shaped better, it might be one of his very best performances. He suggests some of what he had in "The Border" (his least-known terrific performance), the determination of a man hounded by the desire to do good. And he's beautifully relaxed in his scenes with the young Roberts. His paunch and the lines on his face take on the poignancy of a man who has found contentment later than he ever expected. (Nicholson may be one of the rare actors who can play a loving parent without sentimentalizing the part.) He doesn't overdo Jerry's obsessiveness; he makes us feel the danger in Jerry's determination to keep his promise. That's why it's a drag that Penn cuts in Jerry's "visions" or layers voices on the soundtrack as if Jerry were schizophrenic.

At times, "The Pledge" suggests what Bruno Dumont's plodding "Humanité" might have been with an actor in the lead. It's not a fraud, like that much-heralded stinker. I sat through "Humanité" in a state of stupefied fascination, wondering who in his right mind would make a movie that deliberately dull. "The Pledge" is just a bad movie, with more bits of good acting and flashes of director's invention than you get in most bad movies. But it too suffers from crippling ambitions toward aesthetic purity. You can't do a blood thriller when you keep yourself at such a remove from the mechanics. "The Pledge" is a divisive experience; it feels like it was made by a man who thinks that art and entertainment, by necessity, must be two separate things.

Shares