In what's considered a bad neighborhood, a blurry photocopied picture is taped to a leaning telephone pole. "Lost Chicken," it says below the chicken's image, with details in smaller handwriting. The bird was last seen Thursday.

This is not about the chicken, out here with the garbage bags blowing around, and the cars on blocks, and the kids sometimes shot. And it's not about the sign down the street reading, "Found Dog," which suggests that, for every lost chicken, another house gets its puppy back.

This is about Scott Kuzner, who has traveled 3,000 miles to sell two beats.

Kuzner is a 23-year-old aspiring hip-hop professional. He's flown out from Washington to spend the weekend in Anas Canon's basement studio. Among independent MCs, Canon's skills as an engineer are revered -- he just finished touring with Common -- though he himself claims to not care for the genre. Kuzner's pilgrimage to this studio in this neighborhood on this coast is the first major step toward becoming revered himself.

During the day Kuzner is an editorial assistant at Congressional Quarterly. Until this morning, we've only e-mailed. I'd told him that I wanted to watch a person begin a rap career. He'd said OK and invited me to where it was going to happen.

I live three miles away from the address, though I overestimate it and arrive at the house early; with its boarded windows and lost chickens, this neighborhood looks like a place it would take more than 10 minutes to get to. Styles Infinite answers when I knock on the door of the small stucco house.

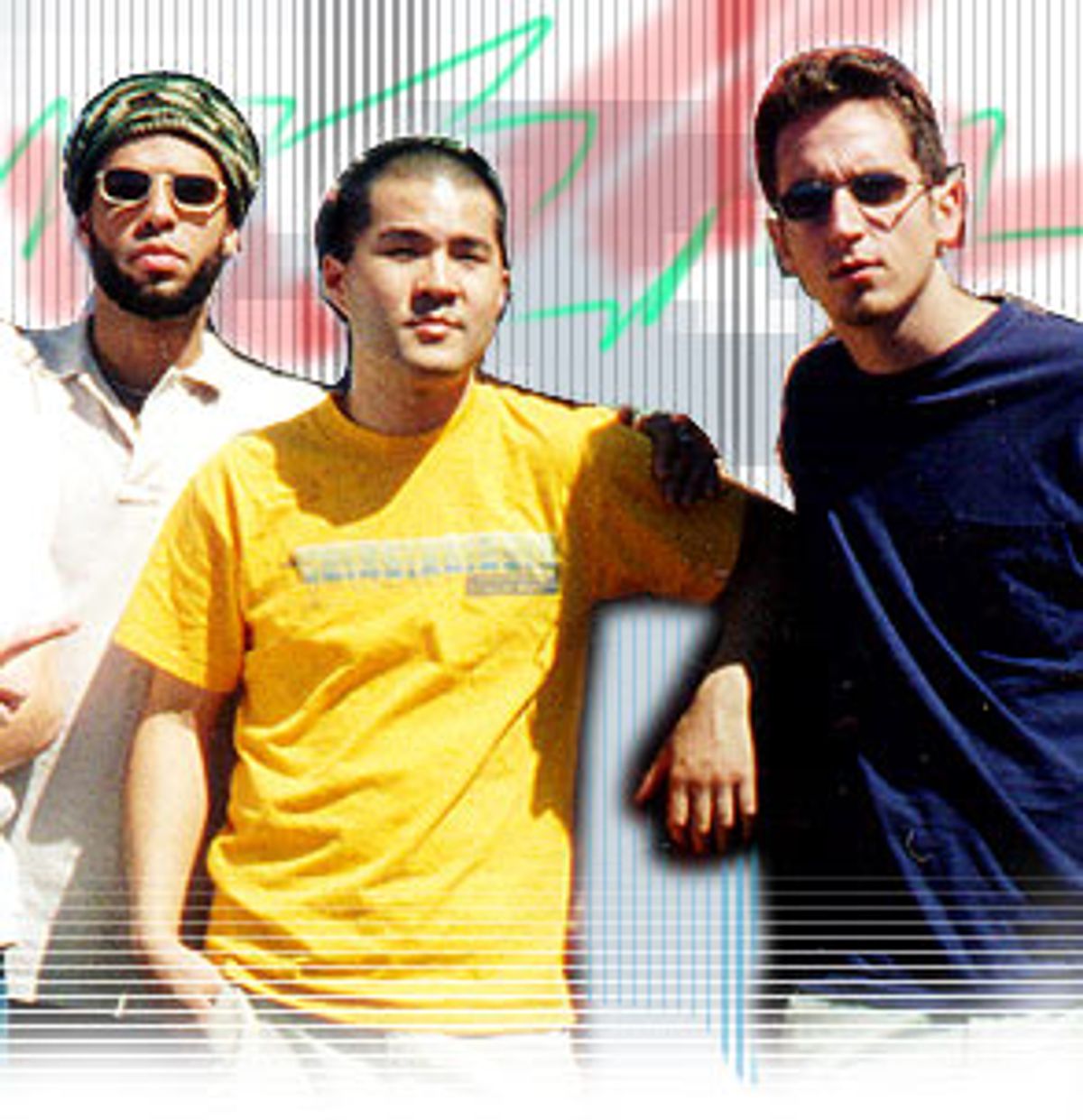

Infinite is also why Kuzner is here -- he's one of the MCs for the Mountain Brothers, a Philadelphia rap trio that's gotten as big as small can get. Hip hop, like jazz and cheese, is for snobs. And snobs find the best stuff underground. Infinite has the quiet, steady confidence of someone who is the best of the underground. He points inside to stairs that go down.

The basement looks like a big, spread-out robot. Wires connect panels to other panels, and these connect to other panels, which are larger than the first. (Later, while I learn that recording sessions are excruciatingly slow, I count 84 cables tangling out of the main panel. By this point I stop calling them panels, but I still don't understand why something that doesn't re-attach severed limbs needs seven dozen cables.)

All the cables and panels cluster around a muscular guy in an old chair with a tank top and cornrows, which look like more cables. This is not Kuzner, I gather, because Kuzner is white. This must be Anas Canon. Canon doesn't look up from his Mackie 8-bus Audio Mining Console.

Then a white guy emerges from behind some equipment. This is Kuzner. We shake hands, and then he introduces me to Canon and to Infinite, who's followed me downstairs.

Scott Kuzner is skinny with a young face and a little hair on the chin. He's wearing shorts, the way East Coasters wear shorts their first time in the San Francisco Bay Area -- they add to the young look. Canon, with his muscles and cornrows, seems older. He moves slowly and deliberately, like someone who knows he can draw people from across the country to his basement. He's being paid $30 an hour, so we stop introducing ourselves and I find a chair. No music is playing yet.

When I found out that Kuzner would be heading my way to cut his teeth in the Oakland hip-hop scene, I pictured the MC trials you hear about: lots of fronting, maybe an impromptu freestyle competition outside, finally some fellas nodding in approval as Kuzner rapped into the studio mic about his women or his car or his flow. As he and I negotiated my tagging along, the truth emerged. Kuzner was indeed coming to the Bay Area to break into the hip-hop world, but not as a rapper. He sells the music that the MC raps over.

All MCs have a producer. This is the person who puts together the sound -- the beat, the keyboard, the sampled guitar, the bass, etc. -- on top of which the rapper raps. Some producers lean heavily on simulated sounds from the keyboard, others dig through stacks of records to find a real Washburn Orleans acoustic jazz guitar being played. Those with money can bring live musicians into the studio -- backed by Columbia Records, for example, Lauryn Hill could afford to pay Carlos Santana to accompany her on her last album.

Kuzner's here with the semi-famous because of a recording he mailed to Infinite, who was then a stranger. "I'd gotten 20-25 tapes," Infinite says. "Scott's was the best."

Having been with the Mountain Brothers for more than eight years, Infinite was looking for a side project (one in addition to medical school) at the time he received Kuzner's recording. He tapped Kuzner and the two hooked up with Canon. If this goes well for Kuzner, it could lead to many more gigs.

"It's hard to get started," Infinite says, "but producers are basically the only people in independent hip-hop who make any money. A successful producer can charge $1,500 to $2,000 per beat."

Kuzner's still getting his sea legs at the $500 level. Canon, logging the names of the tracks and their producer into his console, asks Kuzner for his handle. "Father Scott Unlimited," he replies with the look of someone trying out a nickname for the first time. Canon smiles and Father Scott Unlimited goes in the books.

In front of Kuzner is the sampler he brought with him. Stored on the sampler are all the chopped-up audio elements that he's arranged over the last few months into an original melody. The sampler looks like a drum machine, and each rubber pad corresponds to a different sound. One of Canon's machines will then suck the different sounds from the different pads and lay them onto individual music tracks.

Two songs will be recorded with Canon; "Copacetic" is the one they're working on today. To build its rhythm and melody, Kuzner mined piles of jazz and rap records -- not for good music, but good pieces of music. It takes a funny ear to disregard a tune and hear a song for its bare bones. I picture an architect walking through house after house looking for an especially fine floorboard.

Academics still enjoy calling hip-hop postmodern, the representative form of postmodernism being the pastiche. And though hip-hop still draws predominantly from sampled music rather than live instruments, the pastiche sounds less and less like a pastiche these days. The trend in hip-hop is to cover one's tracks, to reconfigure the guitar, keyboard or drum sounds so thoroughly that their original tune is indiscernible. Puff Daddy made a fortune throwing a new beat on top of the Police's old "Every Breath You Take" in 1997 with "I'll Be Missing You." And it sounded like the Police, only a dance version with Puffy rapping instead of Sting singing. No one serious is doing this anymore, Kuzner says.

For a serious producer making serious music, Kuzner is utterly unassuming today in the studio. Canon is command central, rigging the tracks and manipulating the levels, and Infinite is somewhat of an overseer. Kuzner defers to both. Once he knocks over some shelves. Occasionally he offers an opinion on sound quality, and Canon usually nods in agreement when he does. Mostly Kuzner sits back and listens, nothing on his face to suggest his musical future hangs in the balance. He's very different, Canon tells me later, from the majority of his hip-hop clients.

"Scott's professional. Most rappers come to the studio liquored up and high, so I'm running a circus," he laughs, his Muslim convictions showing. "What would take two hours to produce ends up taking seven. We make so much money on those guys."

You don't want to call Scott Kuzner an unlikely hip-hopper, because he's all about hip-hop being too various for a likely anything. Indeed, he's good at pointing to all the participants in the genre who don't rap about guns, bitches, drugs, malt liquor and beatdowns. But he does so in such a soft, kind voice that it's hard -- and exciting -- to imagine the place he'll politely carve out amid the bravado.

And then you hear the music. He's so good. Not just the beats, either. In "Copacetic," Kuzner arranges the seven jazz guitar chords so tightly, and prettily, that it's difficult to believe someone with twice as much experience could've overlooked this particular musical possibility. Also, he samples live instruments from other records -- most rap music shies away from this great tradition nowadays because of the staggering fees for rights; someone like Scott can generally fly under the radar of whoever's being borrowed from. "Copacetic" is classy, nuanced and, most importantly, catchy; you wake up the next day humming it, and wishing you could hum it more accurately.

Later in the afternoon, Infinite's vocals will prove great, too, but unlike Ice Cube or Dre or Eminem, it's the music that sticks around when the song is over. Still, Kuzner is more than happy surrendering them to someone else's backdrop.

"Is it trippy hearing your own music made into a song?" Canon asks Kuzner, once enough of it has been put together. The closet doors are rattling from the bass at this point. Kuzner nods and laughs, then turns back to his equipment.

Kuzner's place is in the background, the vase for the roses. He prefers it this way. "I'm not trying to be famous," he says, and it doesn't appear to be false modesty. He has rapped in the past, and isn't entirely against doing it again in the future, but producing is his thing. His next project, should this one go well, is to put together an album of his own music, but MC'ed by other rappers. He will play just about every instrument himself.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

The problem with rap music this afternoon isn't violent messages for impressionable teens, but excruciating boredom. Canon's negotiation of the mixing components takes hours. He doesn't seem to be suffering as he arranges each level of each sound on each segment of each track. From the sidelines, one develops a healthy appreciation for George Martin, Quincy Jones and the world's other great producers: It's not just creativity, it's creativity in the face of extremely tedious knob-turning.

One story has George Martin sticking a microphone in a toilet to get just the right sound on a certain Beatles song. This is not that. There is no wackiness here, just solid, attentive and impressively obsessive engineering. What Canon is perfecting will be noticed by less than one percent of the listening population, which will constitute less than 1 percent of the overall population. Getting a single snare sample to sound not too cheap, and not too tinny, but also not too produced, takes 40 minutes. Infinite uses the time to go over his lyrics -- he's yet to fully match them up with the music -- and Kuzner does something with his sampler that I can't see.

At 3 o'clock, Infinite, Kuzner and I decide to go get lunch. "I can't believe how boring this is," I say when we're in my car. Infinite and Kuzner agree, perhaps a little proud of what the boringness says of their commitment and work ethic.

We talk about details. There is the question of whether the guitar should be divided into separate tracks when we get back. There is the question of whether to "saturate" the tape (doing so eliminates noise, but could cause "bleeding," which is when the magnetic particles imprinted on one track migrate over to the next). Kuzner and Infinite agree that hip-hop requires a sober mind.

"There's no way Dr. Dre produces when he's stoned," Infinite says. Even performing on stage is hard to do drunk, he adds. The need to be tight -- to play tight, to rhyme tight, to have that snare on the record be tight -- this is far more compelling than the lifestyle of rap-video reality.

In fact it isn't until later, when Infinite half-struts into the recording booth, that I see anything remotely resembling posturing. Canon says some of his clients do come in with gold chains and attitude, but Kuzner and Infinite are just folks. We talk about California architecture on the way to the burrito place.

Over our lunch I ask who's hot and who's not. The Roots are still hot, Lauryn Hill is not. I press them on the Lauryn Hill evaluation and they capitulate. OK, she's great, they say. It's a general overreaction to an ultimately unrevolutionary album that they object to. The consensus is that a lot of money went into that record.

Back at the studio, Canon finishes mixing down the music and Infinite enters the glassed-off recording studio. For the next hour he raps. He gets through three verses. Later he'll go back and fill in the stark gaps with scratching and background vocals. The song is about things that are copacetic, such as barbecued ribs, another round of drinks, girls and "the grin that you get when tourists want to take your picture." The rhymes are OK. They're a little forced here and there, and the occasional innuendo isn't all that clever -- to the honey climbing in his chair, he offers: "I'm impressed by the giant size of the [loaded pause] diamonds in your ear" -- but Styles has a good voice, and again, the music goes a long way. When I finally leave the studio, he's wrapping up and preparing to start work on the second song.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Kuzner won't reinvent hip-hop. He has monitored its evolution too closely to care about changing it. Like any active historian, his interest is in cooperating with the established rules. To come in and be the rapper who doesn't occasionally dis other rappers, who doesn't employ a thumping bass or a catchy hook -- this disregard of convention threatens to be boorish, not revolutionary. The fun comes from mastering the language, not editing it.

When I ask him what makes his music unique, how he will be different from all the other rappers, I do so thinking it's a softball pitch for him to slap out of the park. Instead he bunts, vaguely tossing out a few ideas about this or that element of his music being particularly tight. There's something almost socialist about his dedication to churning out good beats -- he's quietly contributing to a growing organism and wants little in return. If he'd like to make a name for himself at some point, it's merely to make his job easier.

"His lack of confidence makes him humble," Canon tells me over the phone. "He's not at the point where he knows he's dope but acts humble -- he's actually humble."

But his humbleness is now being tested. A hip-hop outfit called the Himalayan Project just bought five beats from Kuzner, and it turns out "Finish Line" -- the second song recorded in Canon's studio that day -- will be released in the U.K. in March by a Virgin subsidiary. Finally, "Father Scott Unlimited" has been ditched for something more practical; Scott Koozner, he explains, clears up pronunciation questions that clients had with Kuzner.

I ask both Infinite and Canon if Kuzner will make it. It's unclear what making it entails. Getting a lot of radio time can signal a lack of creativity among independent hip hoppers, but then again Jay-Z, Eminem, the Roots and other big acts have managed to hold on to much of their underground appeal. Infinite and Canon agree on Kuzner's talent -- high praise from a couple of veteran music Stoics.

"It's fun music," Canon says. "So much hip-hop is aggressive and mean. Scott's stuff just feels fun. That's rare."

Shares