In what may be the strongest rebuke yet to Ehud Barak's stewardship of the peace process, Israelis who overwhelmingly supported the prime minister in his 1999 election bid have defected to Ariel Sharon in droves.

Israeli voters are incensed with Barak for failing to deliver peace and allowing his country to spiral perilously close to war. Their faith in him is almost as low as their trust in Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat who, in their eyes, has donned the grim face of a master terrorist once again -- one who sanctions drive-by shootings, car bombs and the lynching of Israelis, seven years after the Oslo Accords convinced the world that he was actually seeking peace. While Barak's team conducts marathon last-minute talks with the Palestinians, the Israeli public has already ceased to care. They want Barak out and are poised to elect a hawkish former general, who has pledged to make Israel's security his mandate, when they head for the polls in two weeks. After four months of bloodshed, it seems, more and more Israelis would rather have safety now than an elusive peace later.

Sharon, a veteran politician, is blamed by many for spearheading Israel's 1982 invasion of Lebanon when he was a hot-headed defense minister. It took 18 years to undo the effects of the general's adventurous and controversial policies, which earned him the nickname the Bulldozer." During that time, more than 1,500 Israeli soldiers lost their lives and Lebanese guerilla fighters routinely sprayed Israeli border towns with artillery fire, forcing residents to spend day after day in special shelters. And Israel's international reputation carries the stain of the Sabra and Shatila massacres in which hundreds of Palestinian refugees were killed by Lebanese-Christian militiamen under Sharon's watch. A campaign slogan adopted by Meretz, a left-wing party that supports Barak's reelection on Feb. 6, seeks to refresh those dark memories in the minds of voters: "Sharon -- Lebanon -- Disaster." The slogan rhymes in Hebrew.

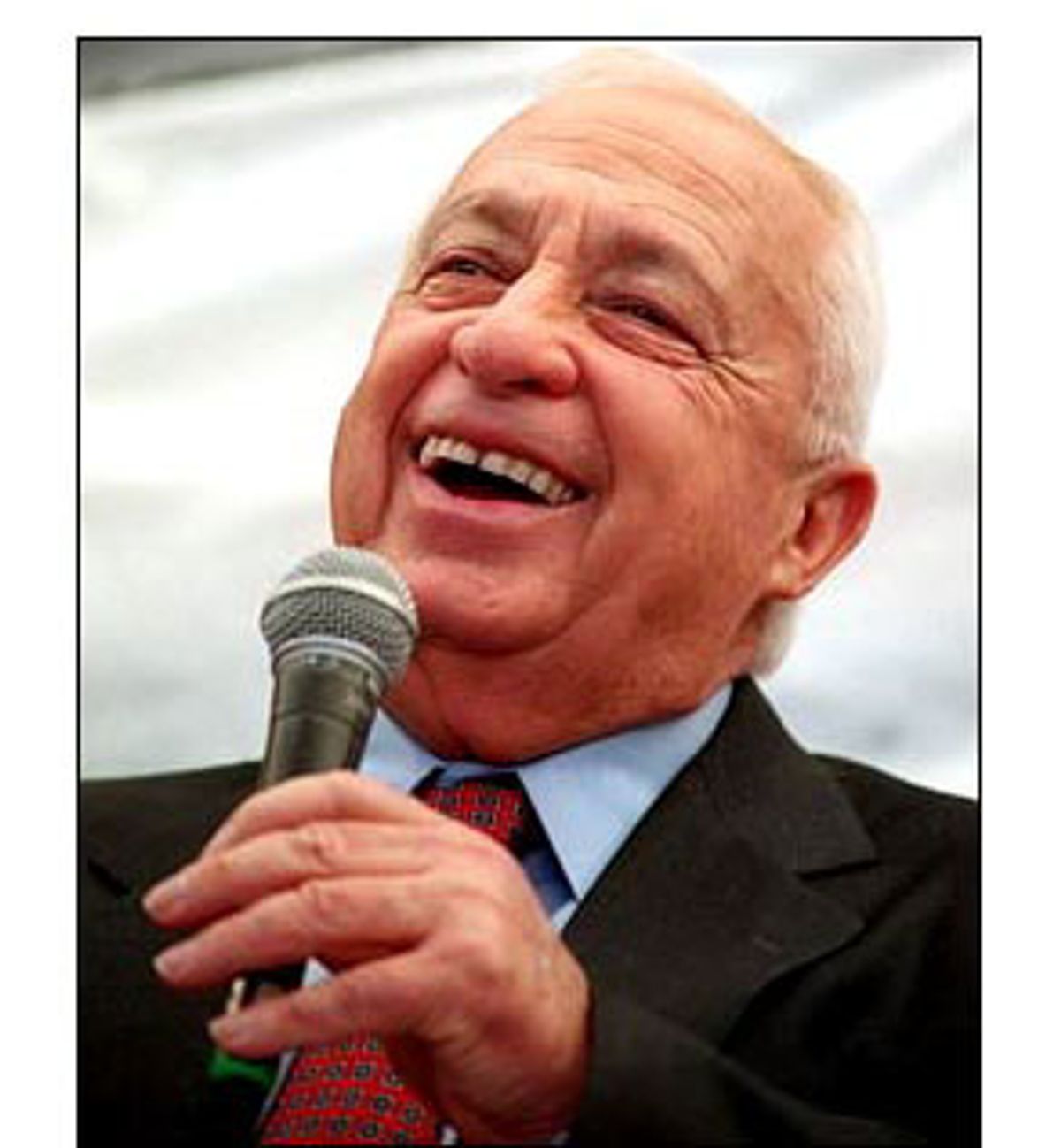

But Sharon has undergone a metamorphosis from Mr. War to Mr. Peace-and-Security at a time when Israel seems rudderless and helpless in the face of a Palestinian intifada. Ironically, that uprising began the day after Sharon made a controversial visit to the Temple Mount -- a Jerusalem shrine held sacred by both Muslims and Jews and the object of rival property claims by Palestinians and Israelis. The violence has killed nearly 400 people and reduced seven years of peace-building to tatters. (The latest victims were two Israeli restaurateurs in Tel Aviv, who were shot by masked Palestinians on Tuesday in the West Bank town of Tulkarem.) But in a time of terrorism and tumult, Sharon's rough-and-tumble image is considered a reassuring asset by many Israeli voters. As the election approaches, Sharon maintains a 20-point lead over Barak in polls conducted by Maariv and Yedioth Ahronoth, Israel's two largest daily newspapers.

To many Israelis, Sharon's record of relying on force in dealing with Israel's Arab neighbors heralds a return to law and order. "He promised nothing," says David Ouzana, discussing a campaign stop Sharon made at his house recently. "But we don't need anything. We know who he is."

Ouzana and his wife Batya are residents of Zarit, a small Israeli town just hundreds of yards from the Lebanese border. Their son was a lieutenant in the Israeli army, one of the thousands of boys bogged down in a protracted and deadly war that Barak promised to end when he was elected nearly two years ago. Barak fulfilled his pledge last May, withdrawing Israeli troops from southern Lebanon. Ouzana's son was one of the last officers to make it safely back to Israel. In a way, Barak saved her son's life.

But Ouzana's not impressed. Palestinian refugees in Lebanon staged a violent demonstration at the border here in October and, if fighting ever resumes between Israel and Lebanon, Ouzana's house sits right in the line of fire.

"Barak saved my son but I'm afraid to stay here. Barak promised to protect us, promised us work, but he has done nothing," said Ouzana, who keeps her 12-year-old twins indoors for fear of sniper fire. When Barak swept into power in May 1999, Ouzana voted for him. But next month, when Israel heads to the polls to elect a new prime minister, Ouzana plans to cast her vote for Barak's right-wing rival Ariel Sharon.

Under pressure from hawkish parliament members since the summer, Barak the would-be peacemaker resigned in early December, triggering snap elections. The stakes for the peace process in this election are enormous. Both candidates are using the words "peace" and "security" like hypnotic mantras in their otherwise lackluster campaigns.

Barak's efforts have gone toward attempting to reach an 11th-hour agreement with the Palestinians -- first mediated by the U.S., then in bilateral "marathon talks" held in the Egyptian resort town of Taba. Those talks were temporarily suspended after the killing of two Israeli civilians on Tuesday but are expected to resume Thursday. Meanwhile, Sharon has been careful not to do or say anything that might undermine the huge lead he currently enjoys in the polls. Political advertising aired by both candidates on TV in the past weeks have had no impact so far on Sharon's 20-point lead; the numbers have held steady for several weeks now.

Fielding reporters' questions in the Ouzanas' living room earlier this month, Sharon put his stance toward negotiating with the Palestinians in evasive terms: "The public knows me, my positions are known and clear, I don't need to clarify them to the public ... I think that what is important to Israel is peace and security, security and peace ... And I think I can bring both peace and security to Israel."

In recent interviews with the Israeli press, Sharon has declared the death both of the process of land-for-peace, begun at Oslo in 1993, and his willingness to compromise in order to achieve an agreement. "The Oslo agreements do not exist anymore. Period," Sharon told a small Hasidic newspaper. However, at the official kickoff for his campaign in Jerusalem on Jan. 10, Sharon tried to strike a more moderate note. "There is no true peace without concessions," he said. "We will achieve peace based on compromise, but we will look out for our interests and make sure the other side keeps its commitments." The question is what he considers to be acceptable concessions.

Judging from comments Sharon made in the Journal of Kfar Habad, a Hasidic newspaper, and from the diplomatic program he discussed in Ha'aretz, Israel's highbrow newspaper, few measures fall under that category. If elected, Sharon has vowed that he would keep all Jewish settlements intact, maintain the status quo in Jerusalem and hold on to the Jordan Valley and other security zones. In those interviews, he also stated that he considered the decision not to reinvade Nablus and Jericho, cities turned over to Palestinian control in the past years, painful enough. "These places are the cradle of the Jewish people, and I know of no other people in the world who would give up their national assets," Sharon told the Journal of Kfar Habad. "The actual recognition that we won't re-conquer these places -- this, in my eyes, is a painful concession."

In other words, Sharon might turn back the clock on the more generous proposals advanced by Barak and President Clinton at Camp David last summer and discussed at Taba in the most recent negotiations. This may agitate the Palestinians further. Indeed, Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat declared in the London Daily Telegraph on Monday that the defeat of Barak would be "a real disaster."

Nor are Sharon's ideas for improving Israel's security and deterrence any more convincing than Barak's. On that mark, they hardly differ -- both would resort to collective punitive measures such as besieging Palestinian towns and more pinpoint targeted measures such as assassinations of Palestinian troublemakers.

But, in an election that is based more on fear than a reasonable debate on policy and principles, the muddiness of Sharon's plans for the future may not deter potential voters. According to a poll conducted by Yediot Ahronot, a leading Israeli newspaper, some 57 percent of Israelis are convinced that Sharon will not succeed in reaching a deal with the Palestinians. That a majority of Israelis still intend to vote for him is a sign of the general peace process pessimism that is afflicting the country.

That gloominess has also infected the spirit of the electoral campaign. Sharon's banners state blandly "Ariel Sharon -- a leader for peace," while Barak's posters at city intersections have been systematically vandalized so that they read "Let's go back to the days of Ariel Sharon" instead of "Let's NOT go back to the days of Ariel Sharon." More reporters than residents turned up to listen to Sharon in Zarit, a chicken-ranching community where entertainment is scarce. And at Sharon's kickoff ceremony in Jerusalem, thunderous applause was reserved for Benjamin Netanyahu, the former right-wing leader who decided to sit out these elections and wait for a less unwieldy Knesset.

A high point in an otherwise bland campaign came during a meeting Monday organized for Sharon at a high school in Negev. A teenager stood up and bitterly accused Sharon of wrecking her life and that of her family by sending the Israeli army into Lebanon in 1982. She said her father had been traumatized by the war and she told Sharon, in a moment captured and broadcast around the world on TV: "I do not think you can be elected prime minister." The left-leaning Israeli press also made much of an interview conducted by Jeffrey Goldberg of the New Yorker last November in which Sharon called Arafat "a murderer and a liar," putting a serious dent in Sharon's campaign claim that he has fought but never insulted the dignity of Arabs.

The campaign would no doubt be more electric if young-wolf Netanyahu were running rather than Sharon, who is portly and tame-looking at 72. But perhaps Netanyahu, with his intensely polarizing character, would not be as successful as Sharon when it comes to wooing centrist or undecided voters.

After visiting Zarit, Sharon showed up in Karmiel, a mid-sized town in central Galilee, at a rally for new immigrants from the former Soviet Union. Many in the audience, fresh off the plane, had never voted before in an Israeli election but seemed receptive to Sharon's avuncular, plain-talking style.

"Barak seeks peace by giving concessions. Sharon also wants peace, but without concessions. I don't really care who's elected as long as there is peace," said Valeryi, a retired engineer from the former Soviet Republic of Azerbaidjan who emigrated to Israel six months ago. (He declined to state his last name in an interview.) New immigrants from the former Soviet Union have no personal memories of Sharon's Lebanon war blunders and are not as committed to the ideological left or right as veteran Israelis. Valeryi indicated he would probably vote for Sharon. "The Arabs, first they take your finger, then they take your hand," he opined on his way to the crowded reception hall.

The "Russian vote" represents about 17 percent of the electorate and has been key in swinging other Israeli elections. Russian-speaking immigrants helped elect Barak in May 1999 and appear ready to crown his rival Sharon this time round. Recent polls give Sharon about 53 percent of the vote in this sector, while Barak is down to 22 percent.

Consultants for Barak still hope to retain a large chunk of the Russian vote. They point to the fact that immigrants from the early 1990s remember Sharon as the housing minister who built cheap, low-quality accommodations for them, far from their workplaces or in controversial West Bank settlements.

But listening to Yulya Poznanski, a 45-year-old woman who left Moscow 10 years ago, such pedestrian history isn't likely to matter much today. "It's not a question of liking or not his housing policy. The country is on the verge of annihilation!" said Poznanski, visibly exasperated. "We need someone to save the country! Someone who will say publicly that Oslo is a suicidal process. We have to stop giving territory to the Palestinians because the more we give, the more appetite they have."

A tour guide in Karmiel, Poznanski has been out of work since the intifada broke out and sunk the fortunes of Israel's tourism industry. "They use violence -- we protect ourselves. We must show decisiveness. Look at the map! Israel is surrounded by a sea of wild, mean and hungry Arabs. Islam is worse than fascism and Communism. Muslims want to conquer the world. You [in the West] will be next," she predicted.

The wave of fear and anger that could easily propel Sharon to power is not confined to Israeli Jews. Polls show Sharon scoring points even among Arab citizens of Israel, a taxpaying, passport-holding minority that represents about 15 percent of the voting population.

Although 95 percent of Israeli Arabs voted for Barak in the last elections, the desire to punish him, a man they hold personally responsible for the shooting deaths of 13 Israeli Arabs in last fall's riots, overrides the deep distaste many have for Sharon. Recent polls give Sharon 8 percent of the Israeli-Arab vote -- not bad for a man Arabs view as a war criminal since the Sabra and Shatila massacres. About half the Arab electorate intends to register its discontent by boycotting the election or casting a blank ballot. And support for Barak has dropped to less than 40 percent. Even before the intifada fanned Arab anger against the Jewish state Arabs felt insulted and bitterly disappointed by the way Barak turned his back on them the moment he was elected.

In this, Israeli Arabs are no different from mainstream secular Israelis who hoped that Barak would push a package of secular reforms instead of caving in to the ultra-Orthodox Jewish minority's demands. Dovish Israelis also find fault in Barak's use of excessive force in dealing with the Palestinian uprising and may choose to snub him by playing hooky on election day. Things are looking decidedly grim for Barak, a prime minister invested with a huge capital of sympathy 18 months ago but whose zigzags in policy alienated many of his supporters in record time.

In the end, Sharon's main advantage is that he is not Barak. "I don't know if he's Mr. Security, but Barak certainly isn't," said Michel Pinto, 32, a cook at a small hummus-and-pita shop on the outskirts of Zarit. "[Sharon] doesn't need to do much. The moment he comes to power, Palestinians will understand. Sharon will act differently -- not like Barak who issues ultimatum after ultimatum and does nothing. The Palestinians have to be calmed once and then it will be better." Barak is routinely accused of being "too soft" and inconsistent in his relations with the Palestinians.

Right-wingers point to the fact that the current-but-halted peace talks in Taba are a result of Sharon's blessedly tough reputation. The hawkish International Christian Zionist Center in Jerusalem congratulated Sharon this week in the following terms: "You have not yet even been chosen as the next Prime Minister of Israel and already your shadow is causing the Palestinians to sit up and finally become serious!" The Taba negotiations are widely seen as a last-ditch effort to save Barak's neck by giving him the outlines of a peace plan he could then sell to the Israeli public on Feb. 6. (The flip side of this diplomatic drive is that any agreement Barak's peace team manages to secure in the next few days will be seen as a base election ploy irrespective of its actual merits.)

Even Barak's greatest achievement, a bloodless withdrawal from southern Lebanon, is under attack these days. In Zarit, Sharon told reporters and residents that he supported an exit from Lebanon but not without first hammering a deal with Lebanon and Hezbollah, the Lebanese guerrilla forces who resisted the Israeli occupation. The "shameful way" in which the withdrawal was carried out by Barak projected weakness, he said, and has had negative repercussions on Israel's regional standing.

In the end, it appears, Barak saved Ouzana's son only to put him at risk again. Less than a year after leaving Lebanon, Avi Ouzana, 22, is now serving in Jerusalem and the West Bank, where stones, bombs and volleys of live ammunition have become part of the scenery. "He risks going to war," said his mother. The question is whether old-warrior Sharon, if elected prime minister, could realistically decrease those odds.

Shares