‘Porn bombs’ or ‘spic and span’?

Some recent press reports suggest Bill Clinton and crew left behind a different sort of legacy at the White House when they departed Saturday. Weekend reports of Clinton aides gamely popping the “W” off of computer keyboards quickly turned to murmurs of vandalism, with Matt Drudge reporting that the damage bordered on the criminal, with phone lines slashed, obscenities scrawled on walls, something called “porn bombs” and obscene messages left on the voice mail system, among other transgressions. Drudge also reported that the incoming Bush administration is conducting a full investigation of these actions.

But by Thursday afternoon, the buzz had died somewhat after White House press secretary Ari Fleischer denied in his afternoon briefing that any “investigation” was going on, though he did say Bush and company were busy cataloging any damage that they had found in the White House. When he was pressed on the details, Fleischer was determined not to be pinned down on any specific incidents, claiming Bush didn’t want to play the blame game on transition messes. “The president understands that transitions can be times of difficulty and strong emotion, and he’s going to approach it in that vein,” he said.

Jake Siewert, the press secretary under Clinton, claims that there’s not much for Bush to forgive, at least not in the West Wing. “The place was really spic and span,” said Siewart, who says he was among the last to exit the building Saturday.

Siewert didn’t think Bush was owed an apology because a little disorder should be expected during a presidential transition. “I was there for the transition back in 1992, and it was a mess, too,” he said. Unlike the new Bushies, however, the Clintons didn’t take it personally. “Imagine if you were at a private corporation with about 400 people working there,” he said. “Then one day, they all left, and another 400 people came in and wanted to run things. It would be chaos.” –Alicia Montgomery [2:35 p.m. PST, January 26, 2001]

White: Tough to swallow

A week after testifying against attorney general nominee John Ashcroft in a Senate hearing, Judge Ronnie White remains upset over how he believes Ashcroft scuttled his own job nomination, a promotion that would have lifted him from the Missouri Supreme Court to a federal judgeship.

White’s convinced it was his pro-choice stance as a former Missouri legislator, not his supposedly soft-on-crime rulings from the bench, as Ashcroft claimed, that doomed his nomination. “The real issue was the right to choose. That’s the only thing he was interested in.” And yet, as he did during the hearings, White declines to comment on whether Ashcroft’s questionable tactics should disqualify him from becoming the new attorney general. He is convinced though that as a Missouri lawyer Ashcroft violated the state’s code of conduct by openly criticizing, and knowingly misrepresenting, his record by labeling White “pro-criminal.”

Rule 8.2 of the state’s Rules of Professional Conduct states: “A lawyer shall not make a statement that the lawyer knows to be false or with reckless disregard as to its truth or falsity concerning the qualifications or integrity of a judge.” Says White: “I thought it was inappropriate for a Missouri lawyer to criticize a judge in that manner.”

White and Ashcroft have a long history. In the early ’90s, White served in the Missouri General Assembly at the same time that Ashcroft was the state’s ardently pro-life governor. The two often clashed over abortion legislation, particularly in 1992 when White engineered a vote to defeat anti-abortion legislation. “I was chairman of a committee and through legislative maneuvering I outmaneuvered them and killed the bill. It was perfectly legal to do that,” the judge recalls.

Ashcroft barely mentioned the words “life,” “choice” or “abortion” during his crusade against White, instead opting to paint him as a dangerously lenient and out-of-step judge. “That’s because the choice stuff is a little more complex than crime,” explains White. “If you say crime, then who looks behind it? But if you say anti-choice than that requites a little bit more discussion. So he took the easier of the two.”

The centerpiece of Ashcroft’s campaign against White involved cop killer James Johnson, who was convicted of killing three sheriffs and the wife of another. In April of 1998, White was the lone member of the Missouri Supreme Court to vote against the death sentence, arguing Johnson had inadequate counsel. During an August 1999 press conference, Ashcroft held up the Johnson opinion as the key reason he was opposing White; the judge was opposed to the death penalty.

White, who has voted for the death penalty 70 percent of the time, says he was stunned that opponents used the Johnson case against him. “That was manufactured because on the day the decision was handed down no one said a word. I don’t even remember it being reported on television. So how, after 16 months, did it become an issue?”

Then came Ashcroft’s now infamous October speech on the floor on the Senate in which he railed against White, labeling him a “pro-criminal” judge who had shown “a tremendous bent toward criminal activity.”

“I watched it on C-Span and sat there in shock listening to him,” White recalls. “But there was not notice or opportunity to respond to it. And I got a call about an hour before the vote was taken from a person in the White House who said the Republicans in the Senate are not talking to our people; do you know what’s going on? I said no, I don’t know. I said, I’m here in Missouri. Find out and let me know. That was the first inkling I got that it wasn’t going to happen.”

Afterward, White says, “I just got on with my life.” But now with Ashcroft close to becoming attorney general, and after having had to relive his disappointment, White has become angry. “Here I am, the first African-American on the Missouri Supreme Court, 47 years old, never been arrested or convicted of anything and yet I’m being called a criminal publicly.”

Would Ashcroft ever have used that language with a white nominee? ” I don’t know,” says the judge. “But he used them with me and that’s what caused the problems. He could have always put a hold on my nomination. He could have always just voted no. But he let my nomination out, strung me out through the process and then killed it in the end.” –Eric Boehlert [2:15 p.m. PST, January 26, 2001]

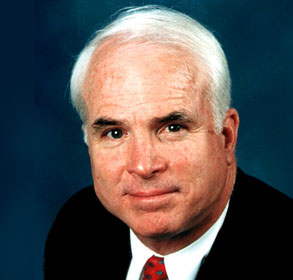

President Bush is finding that Washington’s war horses aren’t as impressed with his sparkling personality as the American electorate was. In separate meetings with former foe Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., and leading congressional Democrats, the president was challenged to fix the system that led to his election.

Bush had invited McCain to the White House to discuss campaign finance reform, presumably to get the senator to back off his insistence that his reform plan be put on a fast track in Congress. But McCain was undaunted.

Though neither man described the meeting as a failure, McCain left still determined to push the McCain-Feingold-Cochran bill through the Senate as soon as possible, and Bush remained convinced that the bill is misguided. Republican legislative leaders agree with the president. In the past, they have been able to sink similar campaign finance reform efforts through procedural maneuvers, but McCain thinks that he now has enough votes on his side to overcome obstructionist tactics like filibusters.

That could explain why Bush doesn’t want to wait on election reform. In a meeting Wednesday with Democratic leaders of Congress, Bush agreed that his long standoff with former Vice President Gore was a signal that local electoral practices need serious attention from the federal government. Some Republicans, and perhaps Bush as well, think that the best way to put off McCain’s ambitious reform package is to tether his bill to a broader election reform plan that has yet to be drafted.

Attorney General-designate John Ashcroft has yet to be confirmed or even voted on by the Senate Judiciary Committee. Now new allegations have bubbled to the surface that suggest he may have discriminated against people on the basis of sexual orientation. Paul Offner, who was interviewed by then Gov. Ashcroft for a Missouri government post, claims that Ashcroft’s first question was about his sexual orientation.

That contradicts Ashcroft’s testimony before the Judiciary Committee last week, when he said that he could not imagine asking someone about sexual orientation during the hiring process. Consequently, questions about Ashcroft’s honesty could give his opponents in the Senate a new basis for disapproving his nomination.

The allegations could also enliven anti-Ashcroft pressure from gay rights advocacy groups. Former Ambassador to Luxembourg James Hormel has joined the anti-Ashcroft bandwagon. Ashcroft was one of a handful of Republicans who tried to scuttle Hormel’s nomination by suggesting that Hormel’s “homosexual lifestyle” made him unfit for the post. Bill Clinton gave Hormel the job anyway using a recess appointment.

Amid the mixed signals from Ashcroft’s foes about his progress, his friends are getting impatient. Senate Minority Leader Tom Daschle, D-S.D., has reportedly assured the president that Ashcroft will be confirmed. On the other side of the aisle, Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott, R-Miss., has slammed the nominee’s opponents as “extremists.” He wants the Democrats to stop the delays so Ashcroft can clean up the “cesspool” at the Justice Department.

— Alicia Montgomery [6:30 a.m. PST, Jan. 25, 2001]