Stuart Garrett and Ted McCagg, both 30, are senior staffers at the Young & Rubicam advertising agency on Madison Avenue. As a creative team they’ve cranked out ads for products like 7-Up, Pennzoil, Teflon and Propecia (the hair growth drug); but it’s not often that they get to design really big campaigns. So when the New York mayor’s office approached them about creating an extensive subway initiative that, instead of targeting bald men, would speak to women about getting out of abusive relationships, they jumped at the opportunity.

“It’s a relief to do things that actually have some redeeming social value,” says McCagg. And it wasn’t too hard for them to switch gears, since the strategy behind creating a public service ad isn’t much different from that for pushing a product. “You’re still selling something,” says Garrett. Adds McCagg, “You have to get into the mind-set of whoever’s going to be reading the ad and try to get them to act on something.”

Working under Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s Commission to Combat Family Violence (created in 1994 just after Nicole Brown Simpson’s murder), Garrett and McCagg designed two major public education campaigns for New York’s subway system; one ran in the fall of 1999, the other last year. The goal was to sell an idea and an impulse item. The idea: Domestic violence is a real problem for many women. The impulse item: A 24-hour hot line set up by the mayor’s commission for victims of domestic violence.

Garret and McCagg were particularly thrilled about the subway as a canvas for their work. “You can actually do what’s called a ‘brand train,'” explains Garrett. “It’s when you purchase one whole side of the train car. You get the majority of the city being forced to stare at the ads. It’s incredibly effective.” Both thought it would be the perfect way to deal with the thorny issue of domestic violence. “It isn’t something that people want to confront. But when the ad takes up the whole train, it’s something they can’t avoid,” says McCagg.

I found myself in one such “brand” car, unable to avoid the ad during my morning commute one day. Dozens of young female faces smiled down at me from the top panel. High school portraits, one after the other, ran down the subway car, beaming that look of the enlightened yet innocent, hopeful yet tentative, empowered yet girly.

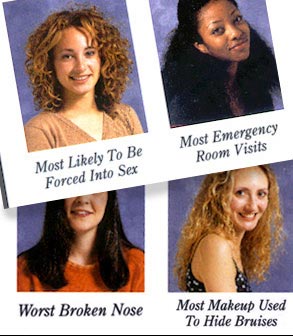

Below each picture, in italics, were yearbook-style superlatives — but not the kind you’d expect. Instead of “Best Dressed” or “Most Likely to Succeed,” they were “Most Likely to Be Stalked,” “Most Likely to Be Forced Into Sex,” “Most Stitches Found on Forehead,” “Most Bruises,” “Most Ashamed of Her Abuse,” “Most Excuses for a Black Eye,” “Most 911 Calls.”

Beneath the pictures were foreboding black and red posters with the slogans “For many high school and college girls, the hardest thing to learn is how to leave an abusive relationship” and “You don’t have to be married to be a victim of domestic violence.”

The yearbook motif was evocative of Garrett and McCagg’s 1999 domestic violence campaign, which featured a similar barrage of women’s faces or upper bodies along the top panel of an entire car. In this campaign, the women’s faces were textured by bruises, cuts and scars. Some of the faces had more wrinkles; some were wider, some darker; but they all looked like they’d been through hell. Below the pictures were a time ticker — 12:01:12, 12:01:24, 12:01:36, etc. — and the slogan “Every 12 seconds, another woman is beaten by her husband or boyfriend.” It was a powerful, eye-catching campaign that made headlines and drove up hot-line calls by 14 percent.

The pictures definitely were provocative. They said women get beaten, every minute, every day, and they’re in pain. But the pictures also seemed to border on sexualizing violence. The women were in tank tops or button-down shirts, leaning up against a wall, sweating or bleeding. And there was something else: Some expressed anguish, others sorrow or fear. One held her head in her hands. None seemed angry. These women looked defeated, exhausted, violated. They were victims with a capital V.

This year’s campaign is no less unsettling — for some of the same reasons. It tells us that high school and college girls are at risk; that partner abuse is so pervasive, many girls won’t be able to avoid it; that if they find themselves in an abusive relationship, these women need to get themselves out of it; that they can start by calling the mayor’s hot line.

Implicit in the lineup is a valiant effort at political correctness: For every two or three white faces in the ads, there is one of color. But they all look pretty damn WASP-y. Almost all the girls have long hair; most are wearing muted jewel-toned shirts, small earrings or no jewelry, or maybe a gold chain necklace. Not one has a shaved head, multiple piercings, dreads or tattoos. You can almost smell flowery perfume, the pressed powder, just by looking at them.

The message is: “Nice girls, educated girls, can get abused too, you know.” And there’s nothing explicitly disgraceful about that message. But it does give credence to the perception that other “types” of women invite violence, or are more prone to it — as if to say, “You already know that those other kinds of women are getting hit; but did you know that well-off girls get hit too?

The simple abundance of young women labeled by their dismal futures (“Most Likely to Be Killed by Her Boyfriend”) gives domestic violence an air of predictability and inevitability. This year the message is young women will become victims. Last year the message was women are victims — every 12 seconds. Both campaigns convey a sense of resignation: This will always happen; boys will be boys, so let’s give the girls a phone number and help them help themselves.

And that, perhaps, is the most disturbing aspect of both ad campaigns: The abusers are nowhere to be seen. The focus is unabashedly on the victims. And the yearbook campaign takes it one step further, implying that girls are being abused because they just haven’t learned how to leave: “For many high school and college girls, the hardest thing to learn is how to leave an abusive relationship” — as if there is, or should be, a capstone course on the subject.

Of course studies have shown — over and over again — that leaving an abusive relationship is often the most dangerous part of the process. The majority of domestic-violence-related deaths occur after the victim has left or is preparing to leave. By focusing on women as victims, the campaigns are giving women alone the responsibility to make the abuse stop. The blame ends up, somehow, on their shoulders. Isn’t it the abusers’ responsibility to stop? And don’t they ride the subway too?

Garrett and McCagg insist that men (95 percent of abusers are male) are affected by the ads. “I think it’s hard for them to look at it,” says McCagg. And that may be true. They may see the ads and be shocked; they may be forced to think about the problem while sipping their morning coffee. At best they’re going to feel sorry for the victims, maybe even decide to reach out and help someone they suspect is being abused; at worst they’ll be titillated. But the ads are not going to force them to think about how they might be contributing to the problem.

If the majority of New Yorkers see these ads, so do the majority of the city’s abusers. If they’re trying to sell the idea that domestic violence is a crime that needs to stop, why do the ads relay a message that is intended for only half the target audience?

The first thing crisis advocates have to learn is not to blame the victim. Our culture tends to react with sympathy toward the man who was robbed, but blames the woman who was raped. We ask the victim of domestic violence, “Why don’t you leave?” but we rarely ask, “Why won’t he stop?”

To an extent, feminists have succeeded in curbing this double standard. Police departments have created special units to train officers in victim support rather than victim blame; hot-line workers are told to talk in coulds instead of shoulds. But the line between empowering and burdening is paper thin, and the mayor’s ads rip right through.

If we’re going to burden people, let’s burden the perpetrators of the crime. Did the mayor’s commission ever think of putting pictures of boys up there as well? How about punks, nerds and jocks with the credits “Most Likely to Push Girlfriend Down Stairs,” “Most Violations of a Restraining Order” and “Most Likely to Rape His Prom Date”? Garrett and McCagg say they thought of that, but the commission was explicit about keeping the focus on the girls.

“We were very limited in terms of resources,” says Amy Yoon, deputy director of the mayor’s commission, even though Young & Rubicam donated its creative talent and Giuliani allocated $300,000 to each of the campaigns.

“Certainly we wanted to get the message across to the batterers to stop; but more importantly, if there is a woman in a situation, we want her to go and seek help immediately,” Yoon says, adding that if they had juxtaposed yearbook shots of young men and women, “the audience would have been confused, because you’re shifting the focus from one extreme to the other.”

Would it have been more confused had the ads addressed domestic violence in nonheterosexual relationships as well? You don’t have to be married to be a victim of domestic violence, but you also don’t have to be straight or female. In fact, studies show that domestic violence affects 25 to 30 percent of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender relationships — the same as the estimate for the heterosexual community.

Diane Dolan-Soto, domestic violence coordinator at the NYC Gay & Lesbian Anti-Violence Project, says that neither ad campaign spoke to her community in any visible way. “The implication for most folks is that heterosexual women are the only victims of domestic violence.”

McCagg and Garrett say they tried to include “ambiguous” women who “could be either/or.” And Yoon argues that the ads are inclusive, that it is the fault of the viewer if he or she doesn’t look at the pictures and think of abuse in lesbian relationships as well. But Dolan-Soto disagrees: “If there was a lesbian there, how would you know? If there was a bisexual woman there, how would you know? If they were transgendered, how would you know? And there are certainly no gay or bi men.”

You can’t expect viewers to make assumptions, she says. “People don’t magically decipher what domestic violence is or which relationships it can happen in — if it was that clear and easy we wouldn’t need to do outreach and education about it.” For an ad to be inclusive of people with different sexual orientations, it needs to be explicit, and most are not, she explains.

“This lack of visibility further victimizes the [lesbian, gay, bi and transgender] community first by not recognizing that the relationships exist, and second by not allowing victims in those relationships to identify that what they’re going through is in fact abusive and that help is available,” Dolan-Soto says.

The Giuliani administration is not alone in its narrow focus. New ads created by the Family Violence Prevention Fund in San Francisco feature women’s faces for a message targeting victims. One, for instance, shows a woman wearing sunglasses. Above her are the words “a) Pinkeye. b) Attitude. c) Victim of Domestic Violence.” Below her is the message “The signs of domestic violence often lie beneath the surface. End the silence now by reaching out to those who are in abusive relationships. Make sure they know that help is available.” In its public service ads, Philip Morris shows a picture of a woman and asks, “Are you a victim? Do you know someone who is?”

Over and over again, the message is: Get help if you are the abused, or reach out and help those who are. The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence says, “Don’t Make Excuses. Make It Stop.” The National Organization for Women’s mantra is “Together, we can stop the violence.” A fine message, no doubt. But what about a poster that asks, “Are you an abuser? Do you know someone who is?”

(Not everyone has fallen down on the job. For its hot line, Metropolitan Family Services of Chicago created billboards depicting bruised faces of young women, but the tag lines were directed toward the abusers: “It’s bogus to hit your girl”; “Is this true love?” Instead of hiring copywriters from Madison Avenue, the text was developed by young people for young people. In San Francisco, the Family Violence Prevention Fund ran ads without pictures, just the text “There’s No Excuse for Domestic Violence.” In Boston, the Gay Men’s Domestic Violence Project ran a transit campaign targeted at gay men. “He loves me not” was the text above a tightly cropped picture of a man’s eye. And the organization Men Can Stop Rape in Washington recently created a series of ads targeting high school boys. In one, four male athletes pose together over text that reads: “Our strength is not for hurting. So when other guys dissed girls, we said that’s not right.”)

It’s really no wonder that the mayor’s ads turned out as they did. His Commission to Combat Family Violence looks great on paper — activists, lawyers, judges, healthcare professionals and shelter administrators make up its membership — but it never seems to meet as a group. And it had absolutely no input in creating the ads.

In fact, Safe Horizon, the nonprofit agency that actually runs the city’s hot line, was not consulted about the ads — nor were the city’s shelter workers, the therapists who counsel victims, the psychiatrists who deal with abusers, the police officers who make arrests or the victims themselves. The target audience and message were given to the ads’ designers by the mayor.

Nonetheless, Bea Hanson, vice president for domestic violence programs at Safe Horizon, praises the ads. She says that the advocacy community and the public have offered overwhelmingly positive feedback about both of the city’s campaigns, but especially this year’s, she says, because it got a message across without the brutality of last year’s.

“People found it very hard-hitting and very educational. It really drives home the point about domestic violence, especially in teen relationships — that it’s not acceptable and that there are resources available for victims,” she says. The few negative comments were that the ads ignored that men can be victims too, and that it was “too graphic to think that these girls could be victims of domestic violence.”

Hanson and other activists have struggled for years to make domestic violence more visible, to work it into the public consciousness. Back in the ’70s, as shelters for battered women began to reach out to victims of domestic violence, activists only dreamed of billboards addressing the subject, never mind an entire subway car lined with expensive ads. So it’s hard to be critical of campaigns like these. You almost feel like a spoiled child, pissed off at Santa for bringing you a superdeluxe 10-speed bike of the wrong color.

And when the numbers suggest that the ads have had an impact — this year the hot line saw a 30 percent increase in calls from teens and a 20 percent increase in calls overall — you feel like even more of a spoiled brat.

But Jean Kilbourne, a pioneering ad critic and author of “Can’t Buy My Love: How Advertising Changes the Way We Think and Feel,” insists that we cannot deflect the influence of advertising. She argues convincingly that by portraying women’s bodies as objects, ads dehumanize women; and by sexualizing violence, ads desensitize all of us.

The very last place we should see our self-esteem diminished, our bodies exploited, or violence sexualized, is in an ad about domestic violence. The mayor’s initiatives may have raised awareness and even inspired more women to get help, but they were ill-conceived. I’m thankful that domestic violence is finding its way into the public consciousness, that cities and corporations are funding flashy ad campaigns and hot lines, but that cannot preclude us from being critical, from demanding more and better outreach on the issue.

Domestic violence needs to be redefined as something more than a “women’s issue,” a category that is often dismissed and rarely just about women. If domestic violence is, as the Family Violence Prevention Fund claims, “everyone’s issue,” let’s try selling it that way.

Part 2: A Q&A with ad critic Jean Kilbourne about what happens when marketing targeted to women hits its mark.