Want to listen to a terrorist talk shop in your own back yard? If you're in New York, hop on the 4 train, get off at City Hall and make your way into the federal courthouse at 40 Centre Street.

For much of the next year, downtown Manhattan will be ground zero for America's latest salvo in its low-grade war against alleged terrorist mastermind Osama Bin Laden, the Saudi exile presumed to be camped somewhere inside Afghanistan, under the protection of the Taliban.

After a three-year, multimillion-dollar investigation, the federal government opened its case last week against four Bin Laden associates, accusing them of criminal acts in connection with the bombing of two American embassies in East Africa on Aug. 7, 1998. That morning 224 people died and thousands were wounded in almost-simultaneous car bomb attacks in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

On Tuesday, inside Room 318 of the Federal District Courthouse, a Sudanese man with a light beard and a skullcap named Jamel Ahmed Al-Fadl spent the day recalling his former life as an Islamic warrior with Osama Bin Laden. Al-Fadl's English was poor and he spoke in nervous bursts, but sometimes his words were devastatingly clear. At one point, prosecutors mentioned the U.S. military involvement in Somalia in 1993 and asked Al-Fadl to tell jurors Bin Laden's take on it. "The snake is America," he recalled Bin Laden saying. "We have to cut their head and stop them. Right here, in the horn of Africa.'"

The 1998 embassy bombings were the stated reason for President Clinton's decision to launch cruise missile strikes into Afghanistan and Sudan six weeks later. None of the 70-odd missiles managed to take out Bin Laden, although they did manage to destroy a pharmaceutical plant outside Khartoum, as well as further erode Clinton's already strained credibility, coming as they did just three days after he told the nation that he had deceived everyone about "that woman."

More recently, officials suspect Bin Laden was involved in last year's bombing of the USS Cole in Yemen. Last month, his name was mentioned after the U.S. Embassy in Rome closed for two days in response to threats of a terrorist attack. And Wednesday, CIA Director George Tenet visited Capitol Hill and called Bin Laden's group, Al Qaeda, the No. 1 challenge to America's security. "Osama Bin Laden and his global network of lieutenants and associates remain the most immediate and serious threat," Tenet told senators. "His organization is continuing to place emphasis on developing surrogates to carry out attacks in an effort to avoid detection, blame and retaliation."

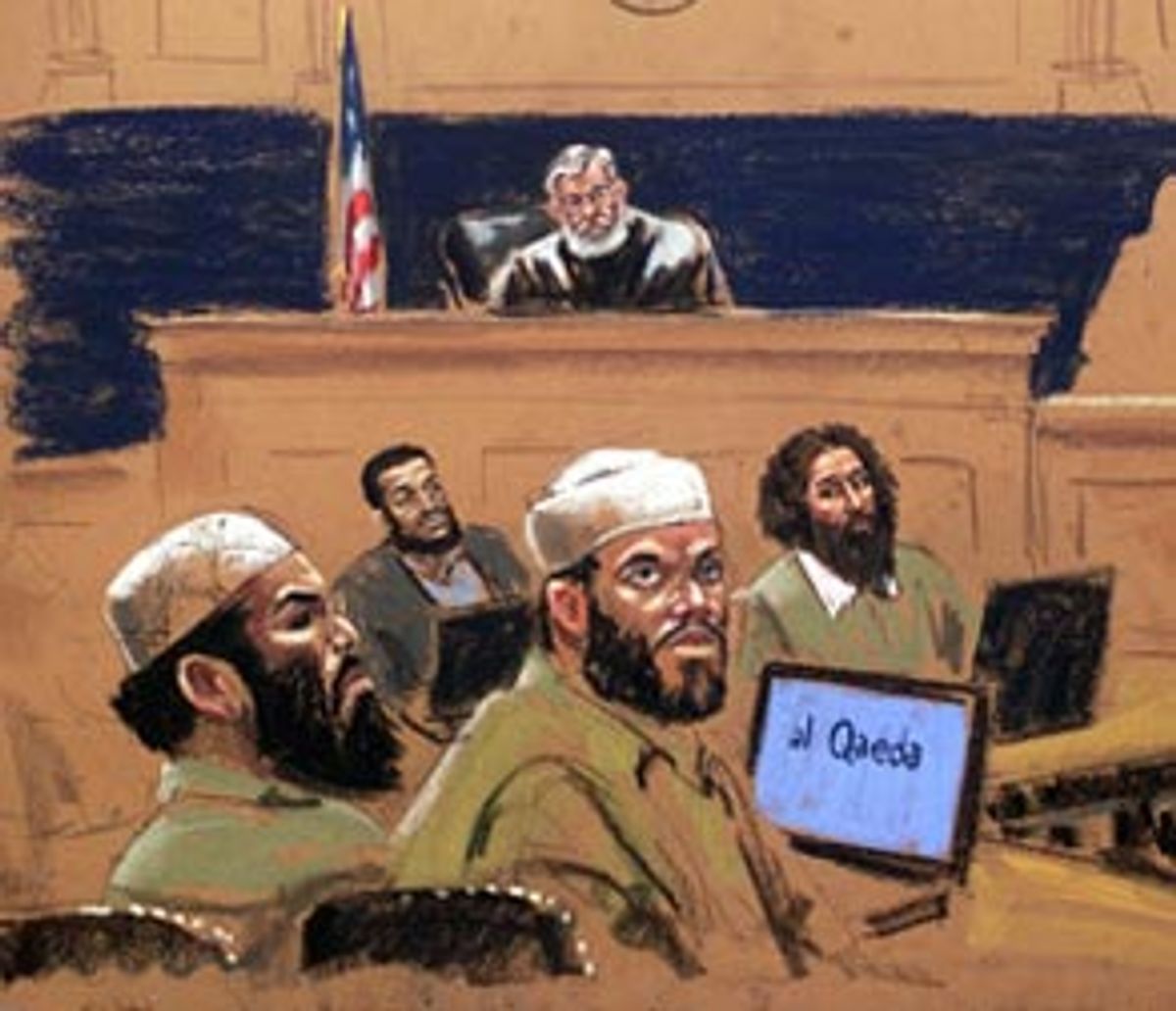

Now America is turning to a jury of 12 New Yorkers to apportion at least some of the blame and to deliver judicial retaliation for what is said to have been Al Qaeda's most deadly day of terrorism yet. The case, appropriately enough, is named U.S. vs. Bin Laden, yet the alleged leader himself, along with 16 others named in the indictment, is not in the dock on trial. This time, at least, the U.S. is trying an eclectic group of mid-level operatives: two alleged bombers, Bin Laden's personal secretary and another member of Al Qaeda with no direct connection to the bombings.

In that sense, at least from the outset, this embassy bombing trial has the look and feel of the recently completed Lockerbie trial. In the Netherlands, two Libyans stood trial for a terrorist act that court testimony demonstrated could not have been the act of two individuals acting alone. The case ended with one conviction and one acquittal, and it left victims' families and some observers dissatisfied, questioning the capacity of such trials to truly deliver justice and contribute in any meaningful way to a decrease in terrorism.

In his opening statement last Monday, prosecutor Paul Butler evoked the sights and sounds around the embassies before and immediately after the bombings. But he also placed the attacks in the broadest possible context in order to fulfil the sweeping scope of the indictment. "The evidence will show that these two bombings were the latest strike in an ongoing worldwide terrorist effort against the United States," he said. "These bombings," Butler told jurors, "were neither the beginning, nor the end of that plot."

Yet the two defendants who face the death penalty in this case -- the first people to confront that fate in a Manhattan federal courtroom in almost 50 years -- are small-time operators accused of participating directly in the embassy bombings. On the surface, the case against both 27-year-old Tanzanian Khalfan Khamis Mohamed and 24-year-old Saudi Mohamed Rashed Dauod al-'Owhali seems fairly solid and unextraordinary. Both men allegedly confessed committing the crimes to American investigators in Kenya. Their attorneys appealed to Judge Sand to throw out those statements, arguing that their clients' Miranda rights had been violated because they had not been offered the opportunity to contact attorneys before making their confessions. In a ruling last week that is almost certain to form one ground for any appeal, Sand allowed the statements to be admitted into evidence, as well as statements made by a third defendant, arguing that the government deserved leniency since the interrogation took place on foreign soil.

As a result of that ruling, the two defendants seem destined to all but concede their guilt. Al-'Owhali made no opening statement while Jeremy Schneider, counsel for Mohammed, used his opening remarks to acknowledge that the prosecution would prove his client's connection to the Tanzanian bomb. He dusted off the Nuremberg defense, portraying his client as a functionary, on trial for actions planned by others; he called his client a "pawn" twice. "He's a nobody, he's a nothing," Schneider said.

Meanwhile, the other two defendants -- Wadih El-Hage, 40, a naturalized American from Lebanon and Mohammed Saddiq Odeh, a 35-year-old Jordanian -- could face life sentences if they are convicted of broader conspiracy charges. In their opening statements, lawyers for El-Hage and Odeh did not distance their clients from Bin Laden, but they did argue that the men were not involved in his criminal activity.

The government's claim to prove a vast conspiracy seemed a bit grandiose until the first witness, Al-Fadl, took the stand on Tuesday. Dressed in a short-sleeve shirt and jeans, Al-Fadl leaned forward in his chair with his hands fixed to his knees and told the court about his time with Bin Laden.

Al-Fadl said he joined up with Bin Laden in 1988, just as Al Qaeda was forming. He testified about the group and the scope of its operations over the next nine years, giving the jury as well observers a peak into life as a terrorist. It cost $1,500 for Bin Laden to send fighters to support the group's base in Chechnya, he testified. He recalled needing to buy 50 camels to smuggle Kalishnikov rifles from the Sudan into Egypt. Then there was the time when, he claimed, he acted as a go-between on a deal for some uranium from South Africa. (Al-Fadl told the court he did not know whether the purchase, for $1.5 million, ever occurred.) When travelling on airplanes, Al-Fadl testified, he always carried perfume and tobacco and avoided talking about religion to keep immigration officials from getting suspicious.

But, as jurors learned Wednesday morning, Al-Fadl was also stealing from Bin Laden, siphoning off $110,000 to buy four pieces of land and a car. When he was confronted by associates he denied it, but he eventually acknowledged his deceptions in a one-on-one meeting with Bin Laden. According to Al-Fadl's testimony, Bin Laden viewed the infraction the way many other bosses might. "I don't care about the money but I care about you because you start this from the beginning," Osama Bin Laden allegedly told Al-Fadl. "If you need money, you should come speak to me."

Instead, he fled, Al-Fadl testified, ending up on a visa line at an American embassy in an undisclosed country, offering to trade information for protection. Five years later, he is living in America in the federal witness protection program with his Sudanese wife and children and a $20,000 loan from the government. In a Thursday interview with an Arab newspaper, a spokesman for Bin Laden denied any connection between Al-Fadl and the Al Qaeda organization.

Al-Fadl's testimony makes great theater and it may well go a long way toward proving the conspiracy that the government alleges. But neither Bin Laden nor his associates are likely to be impressed by America's careful attempt to document and judge his alleged actions. At least one of the defendants allegedly expected to die the day of the bombing, and now all four are poised to become martyrs. The families of the victims, who filtered in for every session this week, may have the satisfaction of seeing men convicted for the embassy bombings, but they'll also learn just how many other people it took to get the job done -- and that may not be so comforting.

Shares