A photograph of my father sits above the television in our living room. My sister gave the picture to my mother as a Christmas present. It's not, however, the original photo.

The original black-and-white snapshot is stored in a photo album my mother keeps in her closet. In it, my father's stern face stares blankly at the camera, intense eyes crowned by thick bristly brows, square chin defining an angular face. My father had the picture taken when he was applying for a green card to come into the United States to work, leaving the rest of the family behind in Tijuana, Mexico.

My sister snuck the photo out of the album and took it to a copy center, where she had them blow it up, add color and remove the milky-colored crease from the corner.

She had them color my father's shirt blue -- an unnatural, manufactured blue, the kind of blue you see on birthday cakes. She placed it in a silver frame with a black velvet backing and little gold leaves on each corner. My mother put the photo on top of the television set, between a picture of Jesus Christ and a candleholder shaped like a leaf.

It's early on a Sunday, a crisp, cold November morning, when the wind shakes the leaves loose, leaving bony branches that scrape against the windows of our house like long nails against a blackboard. These are the kinds of mornings I hated as a kid, because I always found it so hard to get out of bed. I realize that I still hate them now.

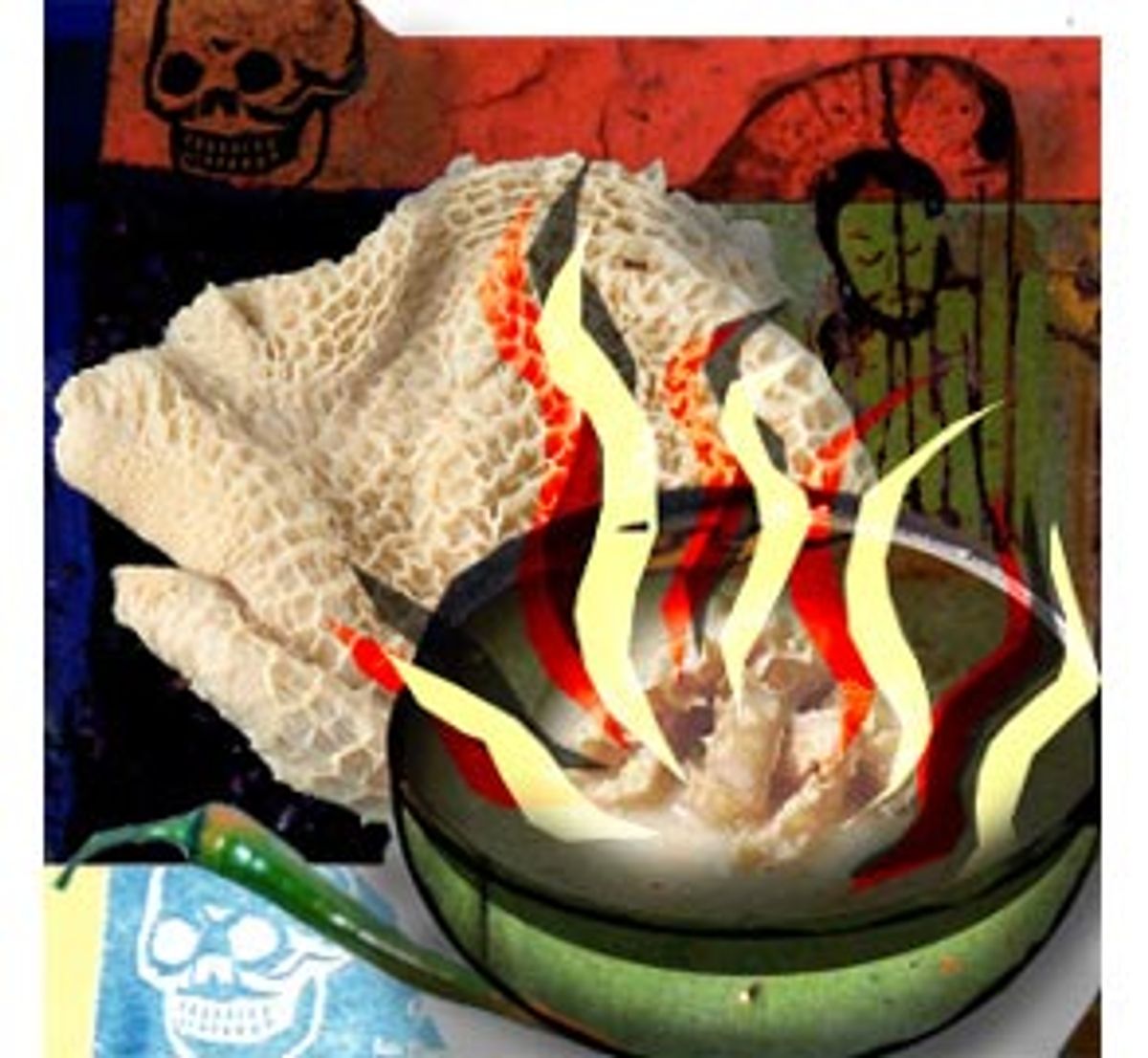

My mother is making her menudo. She stirs the simmering pot and complains about having to sweep the porch.

"I just swept this morning and those damn winds just carry more dead leaves back. Como nada." She covers the pot, goes over to the counter and slowly dices an onion. She asks if I'll be having any menudo today. I tell her yes, but only a little, with no tripe and only a few pieces of hominy.

My mother frequently complains that I'm a finicky eater.

"Why can't you be more like your brothers when it comes to eating my food? Beto, Martin, they eat everything I make. When they lived at home and when they come over now. Asi como nada," she says.

She places the finely chopped onions on one side of the little green bowl she always uses when she makes menudo, its edge warped from the time she accidentally placed it in the microwave. "Ellos se comen todito. Pero tu? Nada!" she says.

She walks back over to the stove and stirs the soup, the water inside boiling the creamy white stomach lining whose smell and appearance have always made me sick.

"I just don't like it, Ma," I say as I flip the channels of the television.

I remember when I was younger, when we still lived in the house on Lang Avenue in La Puente near Los Angeles, when my father was still alive. Every Sunday morning my brothers would wake up, hung over from the previous evening's backyard parties. They would sit across from each other and piece together the highlights from their alcohol-saturated night -- the mishaps, fights, hookups with girls (whose names always sounded like exotic ice-cream flavors) -- and try to calculate the number of beers they had consumed.

They would sit in their thin boxer shorts, their eyes puffy from sleep, their hair mashed up against their heads, the creases from their sheets engraved into their arms, with their heads bent over their bowls in such a way that it looked as though they were praying.

I would sit there, watching and listening, with nothing to say. When they finished, they would wipe their mouths clean and go back to bed.

Then my father would come out of his room, sit in the chair closest to the glass window and eat his bowl, taking in the thick soup with a spoon whose handle was bigger than my arm, and rolling corn tortillas into thin tubes that he dipped into the bowl and ate one by one. He always ate slowly, staring out across the living room, while my mother argued with him about how late it was when he came stumbling home drunk the night before.

Again, I would sit there quietly, listening. I never understood why my father never talked back to my mother, and why he never turned to ask if I had eaten any menudo.

My mother tells me that both of my brothers are coming over today. She tells me that she hopes my brother Beto brings his tools to tighten the leaky sprinkler in the backyard that's flooding the grass. I laugh. It seems as though my mother always finds something to tighten, replace, patch up, hang up or tear down when she knows that one of my brothers is coming over.

My mother asks me what time my friend is coming over.

"This afternoon," I say.

Last week, my mother announced that she would be breaking out the pots and cutting up the tripe to make the menudo, because my brother Martin had said that it had been too long since he had had any of the stuff. I had almost forgotten that I had invited my boyfriend to join us for this Sunday morning ritual.

She asks me if my friend is white.

"Yes," I tell her.

What I don't tell her is that he is my boyfriend and that we have been dating for over three months now. I don't tell her that all those nights I said I'd be studying at the library, I was with him, drinking strong coffee in his living room with our shoes off, kissing on his green-and-white-striped couch with only the hum from his computer breaking the silence.

I don't tell her that the weekend I said I'd be in L.A. visiting my best friend Michael, I spent the night at his house and slept by his side with his chest pressed against my back and his long, thin fingers massaging my stomach.

I can't tell her that a few weeks ago, as we drove down the freeway with the windows rolled down and the radio blasting the latest Green Day album, he told me that he loved me. I can't tell her how good it made me feel.

She asks where I met my friend as she rubs her hands against her thin apron. The steam from the menudo fogs up the windows and seems to hang from the walls and slowly ooze down, clinging to everything, even my own skin, making the inside of the house feel moist and mysterious like the interior of a greenhouse or a sauna.

I tell her I met him at school. She asks if he is a student. I tell her that he finished school a few years ago. She asks if he has family. I tell her they live out of state.

I begin to get a sick feeling in my stomach. I begin to wonder if my boyfriend will have anything to talk to my brothers about and if my sisters-in-law will like him. I wonder if my family will see through my lie and discover that this man is my boyfriend, that this man is someone whom I love.

When the doorbell rings, my brother Beto's daughters are playing in the backyard, and my brother Martin's sons are sitting close to the television watching a puppet named Yankee Doodle Andy sing a song about the importance of friendship. I get up and open the door.

My boyfriend is standing on the porch with a bouquet of fresh flowers in one hand and a dozen Guerrero-brand flour tortillas in the other.

"You got the wrong brand," I say as I open the door to let him in.

He tells me he couldn't remember which ones I told him to get.

"La Rancher," I say. "Remember? The ones with the lady in the mariachi hat on the cover."

He offers to go back. I tell him not to bother. I introduce him to my mother, who is coming out of the kitchen, wiping her forehead with the edge of her apron. She smiles and says "Gracias" when he gives her the flowers and tortillas.

He sits in the living room. My nephews stare at him for a few minutes. I see him smile and wave at both of them. They turn around and continue to watch Yankee Doodle Andy. I sit at the opposite end of our long, peach-colored sofa. I ask him if my directions were clear. He says they were. He can tell that I am nervous because I keep pulling on my earring. He smiles and tells me to relax.

My brothers and my sisters-in-law return from the market with bags of groceries. My brother Martin carries a 12-pack of beer in his hand. I introduce them to my friend. My brother Beto offers him a beer. He politely declines.

The menudo is ready and everyone sits at the dinner table to eat. My three nieces come in from the back and their mother tells them to say hello to my guest.

My mother serves my brothers and their wives big bowls of menudo. She turns and asks how much she should serve my boyfriend. I tell her to serve him a generous portion.

She serves me a small bowl with only a few pieces of hominy and a flour tortilla on the side. Everything is quiet while we eat with our heads hovering over our bowls. Only the sound of our spoons gently tapping the sides of our porcelain bowls breaks the silence. And there is really no need for anyone to say or to ask anything at all.

Later I will go to my boyfriend's house. I will take him a bowl of menudo and three flour tortillas wrapped in aluminum foil. We will sit in front of the television, hold hands and talk about the future -- a house tucked somewhere down a quiet, narrow street with a huge tree in front whose roots have broken through the concrete sidewalk, forcing it up like a camel's hump. We will talk about the photos gathering gray beards of dust that will crowd the top of our television set.

In the center will be the copy of my father's photo in the silver frame bought by my sister.

That night I will watch my boyfriend eat his menudo, leaving a red, swirly film at the bottom of the giant bowl. I will sit silently, listening to the easy, rhythmic sound of spoon hitting against bowl, knowing very well what is going into each careful tap. Knowing now, after all this time, what each one is trying to tell me in its own, simple way.

That night, I will listen.

I will hear the sound of my father's voice. I will hear my mother telling me to stop being such a picky eater and to learn to be more like my brothers. I will hear my boyfriend's love as he finishes his bowl, wipes his mouth, sighs and places his head gently on my stomach. It will be that easy. That simple.

I come home late at night, when the house is dark and thick with tranquillity, with my boyfriend's scent lingering faintly around my neck and fingernails.

I creep into my mother's room, remove the soft pink blanket from her face and gently kiss her pasty cheek.

Before I close the door, I hear her wake up and ask in a muffled voice what time it is. She asks where I have been.

I tell her I was with my friend.

She asks if he liked the menudo, if he ate it all.

I tell her he liked it. I tell her he ate it all.

"You are always alone," she says. "When are you going to bring a nice girl home? Doesn't your friend have a girlfriend? A wife?"

"No," I say softly, in the same voice I used as a kid whenever I knew I was in trouble. "He loves me, Ma. We love each other."

She pretends not to hear me. She clears her throat. She makes the sign of the cross and goes back to bed.

I stand there quietly with nothing left to say. I step out of the room and close the door behind me.

Shares