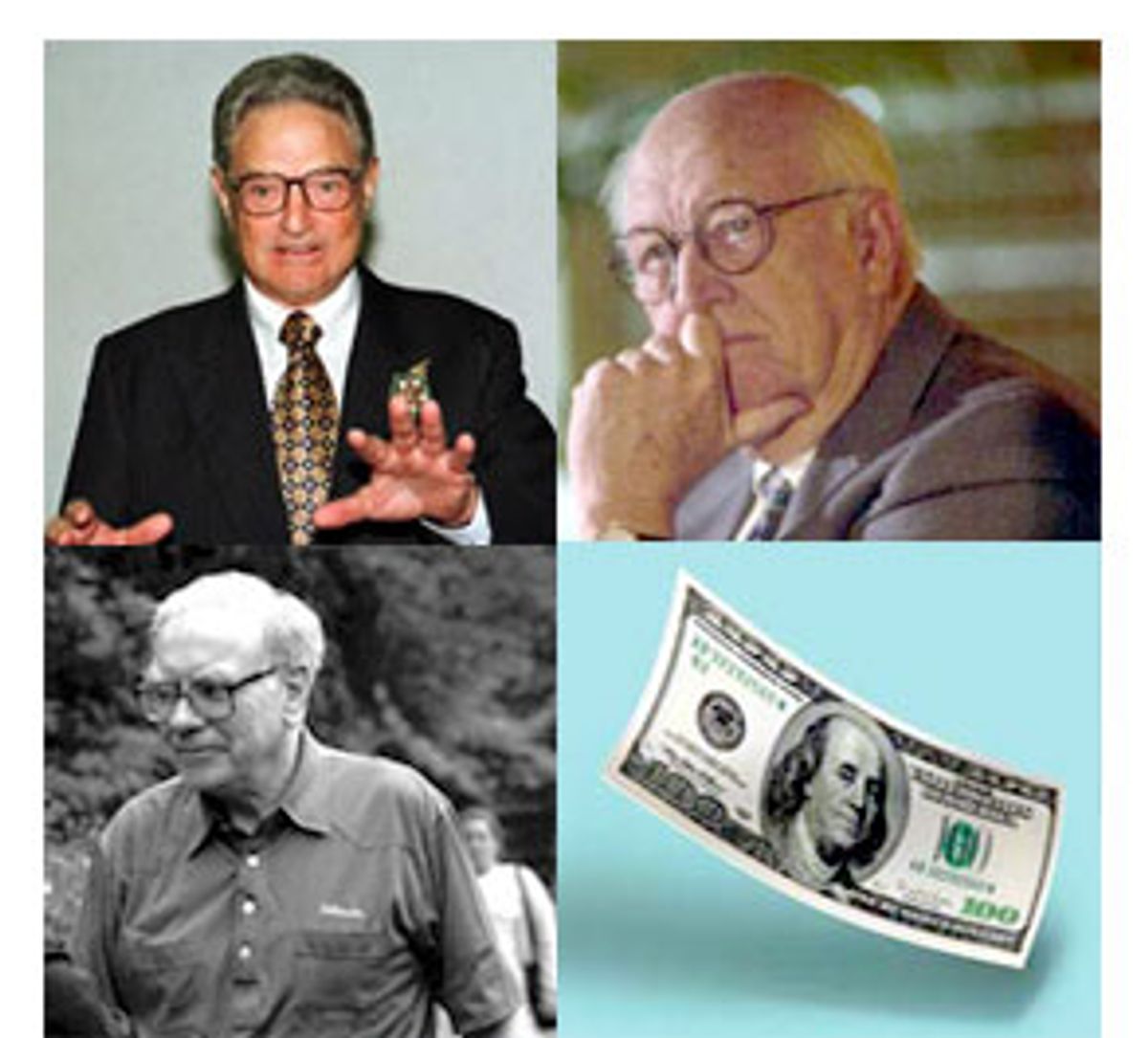

Stand back: Opponents of President Bush's gargantuan $1.6 trillion, 10-year tax cut have finally mobilized a fearsome political counterattack. As befits our neo-Gilded Age, however, so far the big guns aren't Democratic politicians, they're wealthy businessmen. Somehow it's fallen to Warren Buffett and William H. Gates Sr. to fight a major part of Bush's tax-cut package, his proposed repeal of the estate tax, and they're doing it with language that the GOP would blast as class warfare -- if it wasn't coming from rich white guys.

Gates has gotten at least 120 millionaires to sign a petition opposing Bush's estate-tax repeal, on the grounds that it would "enrich the heirs of America's millionaires and billionaires, while hurting families who struggle to make ends meet." Buffett didn't sign Gates' petition, however -- because he doesn't think it goes far enough in denouncing Bush's Robin Hood-in-reverse tax plan.

Buffett's reasoning is must reading for dithering Democrats who haven't figured out how to fight the Bush juggernaut and defend the estate tax, which Bush has masterfully renamed the "death tax." Estate tax repeal, Buffett says, "would be a terrible mistake," comparable to "choosing the 2020 Olympic team by picking the eldest sons of the gold-medal winners in the 2000 Olympics. We would consider that as absolute folly in terms of athletic competition.

"We have come closer to a true meritocracy than anywhere else around the world," Buffett continued. "You have mobility, so people with talents can be put to the best use. Without the estate tax, you in effect will have an aristocracy of wealth, which means you pass down the ability to command the resources of the nation based on heredity rather than merit."

It's remarkable that the most stirring defense of the progressive tax system, and American meritocracy, should come from the world's fourth wealthiest man. Maybe that will insulate him from charges of "class warfare." In any case, perhaps Buffett's attack on Bush's proposed repeal of the estate tax will breathe some life into the demoralized, strangely listless Democrats (the Gilded Age meets the Gelded Age), who don't appear to understand how crucial it is to beat back Bush's brazen tax proposal.

That proposal, which gives a staggering 43 percent of its largess to the wealthiest 1 percent of Americans (though they pay less than a quarter of the taxes), is the foundation of his new world order, a bold attempt to shape the nation's social, economic and political dynamics on behalf of wealthy conservatives for many years to come. Republicans have wailed and gnashed their teeth in the wilderness for almost a decade now, watching as President Clinton made Democrats the party of fiscal responsibility and economic vitality. Clinton paid down the Reagan-Bush deficit by raising taxes slightly on the top brackets, while slowly but steadily (even a little stealthily) expanding programs for the poor, working and middle class, delivering almost $70 billion over five years with such programs as the expanded earned income tax credit, new child health programs and extra subsidies and tax breaks for college tuition.

Now, with surpluses looming, a new president has no excuse for failing to tackle the remaining problems of our winner-take-all economy -- shoring up Medicare and Social Security before the baby boomers stampede toward retirement, fixing our broken health insurance system, and expanding and reforming Head Start and other education programs for poor kids. No excuse, that is, unless he gives away the surplus to his wealthy friends, risking enormous deficits in the process.

Support for Bush's vast tax cut seemed to come out of nowhere. During the primary campaign, polls showed voters preferred Sen. John McCain's deficit reduction plan to Bush's tax cut. Then the slumping economy gave an economic-stimulus fig leaf to the plan. But it wasn't until the Dems inexplicably rolled over, announcing they would be willing to support an $800 billion tax cut (Vice President Al Gore had proposed only a $500 billion cut), that it began to seem inevitable. That sense reached its climax when Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan -- the maestro, the oracle, the world's most powerful man, the guy who defeated the last President Bush, legend has it, by waiting too long to cut interest rates -- backed a big tax cut three weeks ago.

But in recent days the tax cut backers have hit a rough patch. The best news for their foes is the class warfare that's broken out within the ruling class. Buffett and Gates are only the latest defectors. Citibank's Robert Rubin, better known as Clinton's Treasury secretary, has furiously lobbied Greenspan to recant his seeming endorsement of the Bush plan, leading a legacy-conscious Greenspan to backtrack a little on Tuesday. Now Greenspan thinks maybe a trillion-dollar tax cut would be in order, not the Bush plan, which would cost twice that amount.

Rubin himself weighed in Sunday with a center-stage New York Times Op-Ed, blasting the tax cut as "a serious error in economic policy" that would return the country to Reagan-era deficits and economic decline. Rubin deconstructed the fuzzy math behind the Bush plan. The supposed $5.6 trillion, 10-year surplus estimate is only $2.1 trillion once Social Security and Medicare reserves are removed, and Bush's supposed $1.6 trillion cut will actually cost $2 trillion, at least, since it slows the rate at which we pay down the deficit, thus increasing interest payments on the debt. Goodbye, surplus.

Worst of all, Rubin notes, those surplus projections are just that -- projections -- and they're predicated on continued economic growth and productivity gains, which can't be counted upon given the economy's current sputtering.

And while the Dems have struggled to figure out the right way to frame their opposition -- on the grounds of deficit reduction? fairness? the need for at least modest new spending? -- the Bushies have begun to stumble a little. Bush's new czar of "faith-based" programming, John DiIulio, came out against estate-tax repeal last week, arguing persuasively that it would devastate American charities. The Bush team is also demonstrating an uncharacteristic tin ear in defending its proposal.

Treasury Secretary Paul O'Neill -- who disputed the effectiveness of a tax cut to stimulate the economy during his confirmation hearings -- got back on message this week, but he used some unfortunate language. O'Neill defended using both tax cuts and interest rate reduction as a "belt and suspenders approach" to propping up the economy, arguing, "If you can have both, why not have both?" His metaphor couldn't help summoning up images of fat cats in suspenders, used to having belts, suspenders, whatever the hell they want, when they want it -- not the best imagery for a president who's trying to use so-called tax families to disguise the fact that it's his plan that's class warfare. Class warfare by the rich, against the rest of us.

Naturally, Republicans always try to disguise the fact that it is the ultrawealthy who are the main beneficiaries of their tax cuts. In 1981, after the passage of Ronald Reagan's first tax-slashing federal budget, Reagan's budget director, David Stockman, shocked Washington by admitting that the administration's tax reductions for middle-class Americans were "a Trojan horse" to disguise massive cuts for the rich. The statement wasn't a shock; Stockman's honesty was.

What Office of Management and Budget director Stockman didn't admit, at least in his famous series of conversations with the Atlantic Monthly's William Greider, was a far more crucial way the Reagan tax cuts served as a Trojan horse, masking their most dramatic, and intentional, long-term impact -- beggaring the U.S. Treasury in order to force program cuts and spending freezes the Republicans didn't have the political clout to achieve directly. By 1984, the Reagan tax cuts had created a $200 billion budget deficit (Reagan and Stockman had promised the budget would be balanced by then); in total, Reagan and Bush quadrupled the deficit between 1980 and 1992. They screwed the economy, but they triumphed politically, by ruling out new government spending and depriving the Democrats of their traditional means of appealing to their core constituencies -- problem-solving new social programs -- turning them instead into the party of deficit reduction and fiscal responsibility.

And though the party's left kicked and screamed, Clinton took on the new role with relish. But now, when the Democrats -- and the nation -- might have reaped the benefits of fiscal discipline, with a responsible series of programs aimed at curing America's social ills, along comes another Republican president who doesn't even bother with a Trojan horse to disguise his goals of handing the surplus over to the rich, to make sure the nation can't afford new social spending.

It's worth rereading Greider's "The Education of David Stockman" to recall that we've been here before, and it was ugly the first time around. Make no mistake: The Bush tax cut will do much of what Reagan's did -- rule out new investment in healthcare, in education, in housing starts, maybe even in defense. We'll have to at least partially privatize Social Security, because there will be insufficient public funds to save it. "Faith-based" charities -- among their debatable merits, often cheaper than public-sector programs -- will be the only way to provide social services. Private healthcare providers will get a bigger share of the Medicare budget. And we may well wind up with Republican budget deficits, too.

Like Bush, Reagan insisted his tax cut was just the right medicine for what the Great Communicator called a "soggy" economy. (Yesterday, Treasury Secretary O'Neill called ours "soft.") The Reagan camp insisted that massive tax cuts would lead to a balanced budget, or even surpluses -- despite their plans for huge new military outlays -- because the rich would invest more of their money, and earn more, leading to higher tax revenues. Reagan and his team called their new plan "supply-side economics," though skeptics like George H.W. Bush, running for president in the 1980 Republican primary, called it "voodoo economics," and GOP congressman turned independent presidential candidate John Anderson predicted it would lead to massive deficits. They were both right.

Once in the White House, Reagan and his team got busy on behalf of the new approach. Greider details how Stockman "changed the OMB computer" -- in 1981, it didn't seem important to explain exactly how -- introducing a new economic model that projected budget cuts would lead to a decline in inflation, interest rates and unemployment, a surge in profits and productivity, and healthy tax coffers, with lower rates balanced out by higher profits and incomes for everybody.

Of course, it didn't work that way.

Thanks to the Reagan economic program, unemployment rose; so did interest rates. The stock market declined and the deficit ballooned. Later, Stockman would confess to Greider that "supply side" had been just a fancy new term for the inelegantly named "trickle-down" economics. "It's kind of hard to sell trickle-down," he acknowledged, so they came up with a new label. But supply-side architect Arthur Laffer, Stockman said ruefully, "sold us a bill of goods."

Plus, some of Stockman's budget-cutting proposals were rejected. Remarkably, the GOP budget director proposed a "mansion tax," capping the mortgage deduction for luxury homes -- unthinkable 20 years later -- as well as lots of cuts in corporate welfare and pork barrel spending. He was shocked, shocked that such proposals were unsuccessful, while most of the proposed cuts to social programs sailed through. "The hogs were really feeding," Stockman complained, in one of the interview's most memorable, and later regretted, turns of phrase.

The news wasn't all bad for members of the Reagan team. They achieved almost $40 billion in budget cuts in their first year -- eliminating the CETA job training program, affordable-housing subsidies, the poverty programs of the Community Services Agency and legal services for the poor -- and made sure Democrats wouldn't be able to restore the cuts, or enact new social programs, for many years to come. They didn't get everything they wanted on that score -- Stockman proposed "zeroing out" Head Start, for instance, the program now beloved by even Republicans. Even Vice President Dick Cheney, then a Wyoming congressman, voted to cut it. Criticized for that stand during this year's presidential race, Cheney sorrowfully cited the big budget deficits of the early '80s for that now-regrettable vote -- somehow ignoring that it was his GOP buddies who created them. No wonder the Democrats aren't a match for these guys.

Twenty years later, "The Education of David Stockman" is wonderfully educational for all of us, as a primer on how Republicans from Reagan to George W. Bush will manipulate numbers, rely on fantastic budget projections and even lie to achieve their goals. Along with Warren Buffett and Bill Gates Sr.'s defense of the estate tax, it should be delivered to all Democratic members of Congress, to strengthen their spines for the coming battle over the Bush plan. And it would be nice to see some Democratic rabble-rousing on the issue. Maybe ex-President Clinton could take a break from defending Marc Rich and trying to hold on to his lucrative speaking engagements in front of banks and investment houses, and spend some political capital on defending the record of fiscal prudence and tax equity his successor would like to destroy. Maybe Al Gore could put down his journalism syllabus and reassume the populist mantle he wore, unconvincingly, at the end of his presidential campaign.

It's not that there aren't ideas for cutting taxes responsibly, given the likelihood that there will be some kind of budget surplus in the near future. If Congress and Bush really wanted to stimulate the economy and reduce the tax burden equitably, they could issue a one-time rebate -- say, $500 for every man, woman and child. That would have most impact on low- and moderate-income Americans, and on the economy, since they're more likely to actually spend their tax relief than are the rich, who don't need it.

Then there's the plan once sponsored by that known socialist, Attorney General John Ashcroft, to make payroll taxes deductible. Many Americans pay more in payroll taxes -- mostly Social Security and Medicare -- than in income taxes. And the burden has escalated faster than inflation. Since 1970, by some estimates, they've risen 50 percent. Making payroll taxes deductible -- proposed by Ashcroft when he was a senator -- would mostly benefit middle-income families, since those taxes are phased out on incomes above $70,000 annually. But again, they're the ones who need it most, and who are most likely to spend their tax relief and rev up the flagging economy.

Instead, Team Bush has crafted a tax plan that gives almost half its benefits to the richest 1 percent, the Warren Buffetts, the Bill Gateses and of course the George Bushes, too. Refreshingly, the proposal is such economic overkill that at least some of the beneficiaries are saying, "No thanks." (Gates Sr., by the way, says his son Bill is "sympathetic" to his cause, but hasn't signed his petition. He ought to.) Of course a tax policy creating an "aristocracy of wealth," in Buffett's stinging words, makes some sense coming from a man who got into the White House much the same way he got into Yale, as a legacy admission. It's hard not to notice that, rather like choosing the 2020 Olympic team from the eldest sons of the 2000 winners, we chose as our 2000 president the eldest son of the 1988 victor, or at least the Supreme Court did.

It would be nice if Bush, like Buffett and Gates, decided that rich white guys like him have been given enough already -- health, wealth, success and, in Bush's case, even the presidency. But he won't, so the Democrats should remind him. They shouldn't leave it to philanthropic millionaires alone. It would be a shame if the open defense of American meritocracy and progressive taxation, and a frank critique of the dangers of inherited wealth and social status, became luxuries reserved exclusively for the wealthy.

Shares