Amanda Smith, the editor of "Hostage to Fortune: The Letters of Joseph P. Kennedy" and a Kennedy grandkid herself, kicks off the book by recounting her own sepia-toned "single memory" of one of America's most famous fathers. In "what must have been the summer of 1969, the summer before Grandpa's death," Smith recalls preparing with her cousins to meet the family patriarch. Idling on the great lawn behind the Kennedy compound, Smith remembers watching "my shadow's progress across the grass while our baby-sitters reminded us that girls curtsy and boys bow."

There was her "growing anticipation as we climbed the stairs to his bedroom, toward the source of bustle and hum in that otherwise still house," and finally seeing a room "filled with people, all of them orbiting his bed." Her grandfather is an image in "red pajamas," "spectacularly freckled," whom "everyone called by a different name -- Daddy, the ambassador, Mr. Kennedy, Grandpa." Nonetheless, Smith remembers that he commanded the room in "whispered reverence."

When it came time for introductions, she says, another young cousin, instructed to bow to his grandfather, misunderstood and, mimicking an action "familiar to him from cartoons," approached and "launched a tiny fist toward Grandpa's jaw with a screech of 'Pow!'" After that, Smith's memory fades to black.

It's a charming tale that reeks of Kennedy: the oddly appealing order of upper-class formality; the poignant image of the tight-knit clan gathering around their ailing leader's bedside; a wholesome anecdote of one of those spunky Kennedy kids likely to prompt chuckles all around.

It's also extremely unlikely that Smith remembers this. Smith, the adopted daughter of Jean Kennedy Smith, was born in the spring of 1967, which would put her at just a little over 2 years old at the time of this meeting. Scientific research lends little credibility to memories before age 3, when a "childhood amnesia" seems to occur, possibly because the hippocampus, the portion of the brain used to recall a memory, is still forming. Usually, the memories we think we have from that early time are confabulations, patchwork "memories" formed by photographs and, most importantly, the relayed stories of family members.

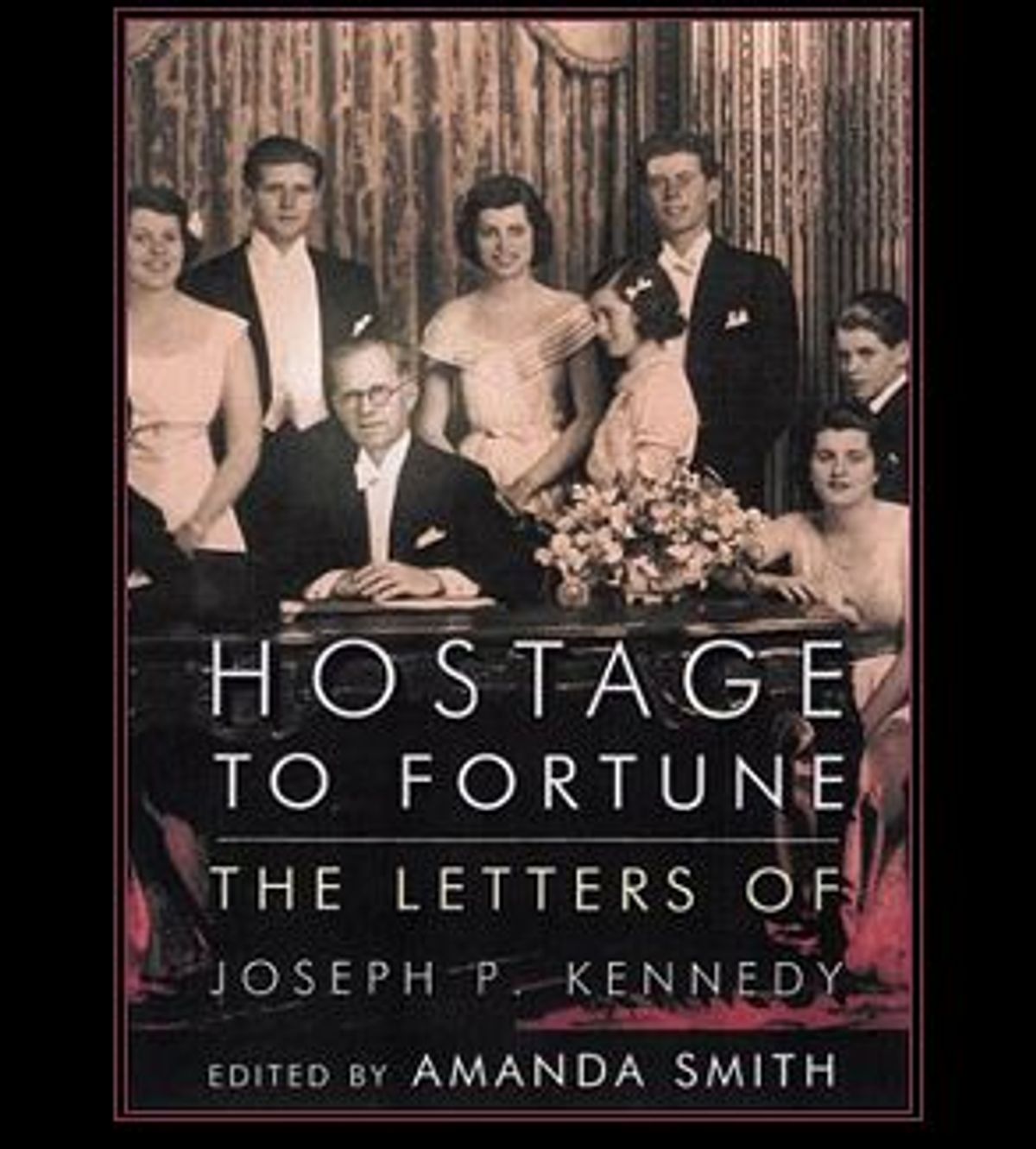

What of it? The editor of a book of letters takes some poetic license to humanize the man at the core of a lengthy (738 pages) collection of letters spanning 47 years. Perhaps it's a niggling point to make, considering the awesome, seven-year effort Smith says she undertook to winnow 600,000 pages of correspondence into this book. Then again, these suspicions are naturally applied to the Kennedys. A reader already approaches this book wondering just how intrepid Smith -- or any Kennedy, or even any Kennedy fan -- could be in choosing the best of Joe Kennedy's letters for mass consumption. Are we getting a glimpse of the real Joe? Not just the family man and feared businessman, but the alleged bootlegging, notorious anti-Semite, the isolationist with a penchant for Hollywood leading ladies and a blood lust for his family's political success?

In this collection, we see much of the former and virtually none of the latter. And it can make for bland reading for a reader unlikely to get very excited about, say, a 1928 letter from Franklin Roosevelt to Joe Kennedy, sussing out whether Kennedy would back New York Gov. Alfred E. Smith's presidential campaign. (He did.) There's certainly an irony to the letter: Roosevelt in an early schmooze with the man he'd later appoint the first Securities and Exchange Commission chairman and, more famously, ambassador to Britain during World War II, before relations between the two men chilled for good.

That letter is going to excite historians more than a general reader. What does become bizarrely gripping, though, is just how unrelentingly positive Kennedy comes across in these letters, which he seems to have taken great care to save for a collection exactly like this one. Whether it's his tough-love dispatches to his children or fawning letters to the press or abject letters to politicians, these letters offer early proof of what we were all to learn: Nobody spun the Kennedys better than the Kennedys.

Smith tries to create a little distance between herself and her subject, her grandfather's trove of letters. She wants to build our trust; she assumes the tone of someone vaguely familiar with the subject but, like us, also an outsider looking in. And in her introduction to each section, she's self-deprecating enough to almost pull it off. She writes early on, "In docudramas, those modern history plays with all the traditional accommodations of fact to histrionics," her famous relatives "bark witty repartee at one another in Katharine Hepburn accents through choreographed touch-football games."

That's a nice touch. And she doesn't shy away from the worst rumors about Joe -- she just doesn't offer much elaboration on them. On the alleged bootlegging? "It is certainly accurate, as it has often been said and as his letters reveal, that Grandpa supplied his tenth college reunion with alcohol in 1922 at the height of Prohibition." Beyond that, though, nothing. About actress Gloria Swanson, who wrote extensively of an affair with Kennedy in her own memoirs, Smith says that her grandfather's letters "never stray from the realm of business and film production." She also acknowledges that "accusations of anti-Semitism would follow him throughout his life," but dismisses many stories and rumors as "secondhand or overheard comments recollected by others years later."

OK. But Smith also acknowledges that his actions as the U.S. ambassador in London gave Jews plenty of reason to be critical. Kennedy was, of course, the Roosevelt administration's most renowned critic of an Allied involvement in the war, and Kennedy never shook a reputation for a pro-German point of view. In one oddly awkward (and not typical) bit of spin, Smith describes her grandfather's role with Germany's Jewish refugees:

Although George Rublee, chairman of the International Committee on Refugees, would complain to the State Department about the ambassador's lack of interest in the plight of refugees from the Reich, the ambassador would personally oversee the emigration of a number of German Jews. He would develop his own alternative to Rublee's efforts, but among the extensive collection of papers, clippings and memorabilia that he took home from London, curiously little information would survive about his plan or its proposed implementation.

And then later:

His attitudes toward other refugees, however, were somewhat more clear-cut, and his efforts better documented. At the request of the mother superior at his younger daughters' school, he enlisted the help of the prime minister and the Anglo-Catholic foreign secretary in the successful evacuation of a number of Sacred Heart nuns from war-torn Barcelona. Describing his reasons for releasing news of their rescue to the papers, he noted in his diary on July 20, 1938, "I wanted to emphasize that the Jews from Germany and Austria are not the only refugees in the world, and I wanted to depict Chamberlain and Halifax as human, good-hearted men, capable of taking an active interest in such a bona fide venture."

While eager to prove that Jews were "not the only refugees in the world," Kennedy was also fairly quick to blame them for his bad press, pointing to the "Jew influence in the papers in Washington," and singling out Walter Lippmann in a letter to his wife in which he wrote that Lippmann "hasn't liked the U.S. ambassador for the last 6 months. Of course the fact he is a Jew has something to do with that." Jews, naturally, were vocal critics of Kennedy during his time as ambassador because of his odd neutrality toward Germany.

Kennedy's letters, as Smith points out, don't discuss the topic very candidly. The correspondence from his oldest son, Joseph Jr., is another matter. Young Joe, traveling through Europe at age 18, comes across as a bit of a bore, a rather thoughtless daddy's boy. His assessment of the German situation, meanwhile, is based on assertions that have a distinctly anti-Semitic flavor:

Hitler came in. He saw the need of a common enemy. Someone of whom to make the goat. Someone, by whose riddance the Germans would feel they had cast out the cause of their predicament. It was excellent psychology, and it was too bad that it had to be done to the Jews. This dislike of the Jews, however, was well founded. They were at the heads of all big business, in law, etc. It is all to their credit for them to get so far, but their methods had been quite unscrupulous.

And then later:

As far as the brutality is concerned, it must have been necessary to use some, to secure the whole hearted support of the people, which was necessary to put through this present program ... It was a horrible thing, but in every revolution you have to expect some bloodshed. Hitler is building a spirit in his men that could be envied in any country.

A sympathetic reader can forgive the immature Joseph Jr., escorted by the local aristocracy on his first major trip abroad, for his nauseating misreading of 1934 Germany. What his letters suggest more than anything else -- and far more than those of any of the other Kennedy siblings -- is an eagerness for his father's approval. It's probably unfair to assume that Joe Jr. was simply parroting his father's anti-Semitic views, but nonetheless, it's impossible to believe he would have thrown any idea at his father if he thought it would be met by anything other than utter agreement.

And it wasn't. "I was very pleased and gratified at your observations of the German situation, and I think your conclusions are very sound," Joe Kennedy replied to his son, allowing that "it is still possible that Hitler went far beyond his necessary requirements in his attitude toward Jews, the evidence of which may be very well covered up from the observer who goes in there at this time." But the ambassador to London had a more pressing question for his son: "If he wanted to re-unite Germany, and picked the Jew as the focal point of his attack ... why then is it necessary to turn the front of his attack on the Catholics?"

But while Joe Jr.'s image suffers in "Hostage to Fortune," those of other Kennedy siblings shine brighter. The letters of a young, constantly ill Jack Kennedy are thoughtful and sensitive beyond his years. Kathleen "Kick" Kennedy's letters to her parents crackle with vivacity. And perhaps most moving are the letters from Rosemary Kennedy, whose mild mental retardation stalled her development in the hypercompetitive Kennedy family. A year older than Kick, Rosemary penned letters (at times, with help) that seem on a par with her sibling's, up to about age 16, when we suddenly start noticing Kick's breathless accounts completely overwhelming hers.

The last letter from Rosemary to her father was sent in April 1940, when Rosemary, 21, signed off with the postscript "I am so fond of you. And ... Love you very much. Sorry. To think that I am fat you . think)." It is unclear exactly where, or when, but some time in 1941, Joe Kennedy decided that Rosemary might benefit from a still fairly unknown prefrontal lobotomy, to help with her reported bouts of anxiety. The procedure, Smith writes, "failed," and there is almost no mention of Rosemary after late 1940 in the patriarch's papers.

Rosemary's situation was the first of the many tragedies that rocked the family. But we don't get much insight into what Joe Kennedy was experiencing or feeling in these later years, when death and personal disaster seemed to stalk the family. His correspondence becomes increasingly clipped and careful. He's always on message -- even spinning in the most casual correspondence with one of the kids' former nannies, who had recently left. "I am delighted that you liked the picture and I think the one in LIFE was very cute," he wrote to the nanny. "Of course I'm getting a bit fed up with hearing that my wife looks so very young, because to really understand that it means that I look like her father and that is a terrible state of affairs after all these years struggling to keep my youthful figure, so I am going right back to chocolate ice cream and plenty of chocolate cake." Too many of his letters are cloying, like this one. They leave a twee aftertaste.

Then again, we're used to trying to understand the Kennedys through their press releases. We're trained, by now, to understand -- and be fascinated by -- the Kennedys through the myths they created, such as "Camelot." And we've learned to understand the dark side of the myth. John F. Kennedy Jr.'s now-defunct George magazine always seemed like a perfect-bound advertisement for him, and it was perhaps most successful evaluated as simply that. He seemed to take great pleasure in tweaking his own family's myths, and those gestures said more about him than any of his brief editor's notes did. Did he ever do anything more bizarrely fascinating than placing a dolled-up Drew Barrymore in Marilyn drag on George's cover with the tag line "Happy Birthday, Mr. President"? That really had nothing to do with politics, or celebrity, or anything else George was supposed to be about; it had everything to do with him and his family. (And trying to sustain the magazine after Kennedy's death seemed either entirely beside the point or a rather gross exploitation of a tragedy.)

In these letters, the real essence of Joe Kennedy emerges less in the revelations about his controversial professional history, or even the tragic lives of his children, than in his desperately eager, sycophantic drive to control his public image -- with reporters' puff pieces and, presumably, with us, in later "diaries" he kept, apparently for eventual publication. With their chattering prose and embedded notes reminding him to add a comment from Jack here, an observation from Rose there, you can see that he had a clear vision of how he wanted the world to view him: as a lovably wise and decent family man, sage businessman and savvy politician. By showing us his desperation to see that image realized, "Hostage to Fortune" ends up eroding its foundation.

Shares