Readers opening the pages of the New Yorker last Oct. 30 found an unexpected tidbit in the midst of the usual Talk of the Town items -- a small humor piece entitled "Proverbs According to Dennis Miller." Among the short parodies of Miller's reference-heavy style: "A bird in the hand ... is dead or alive, depending on one's will," and "What goes up ... will stay up if it has an escape velocity of 11.3 kilometres per second." The byline was Johnny Carson.

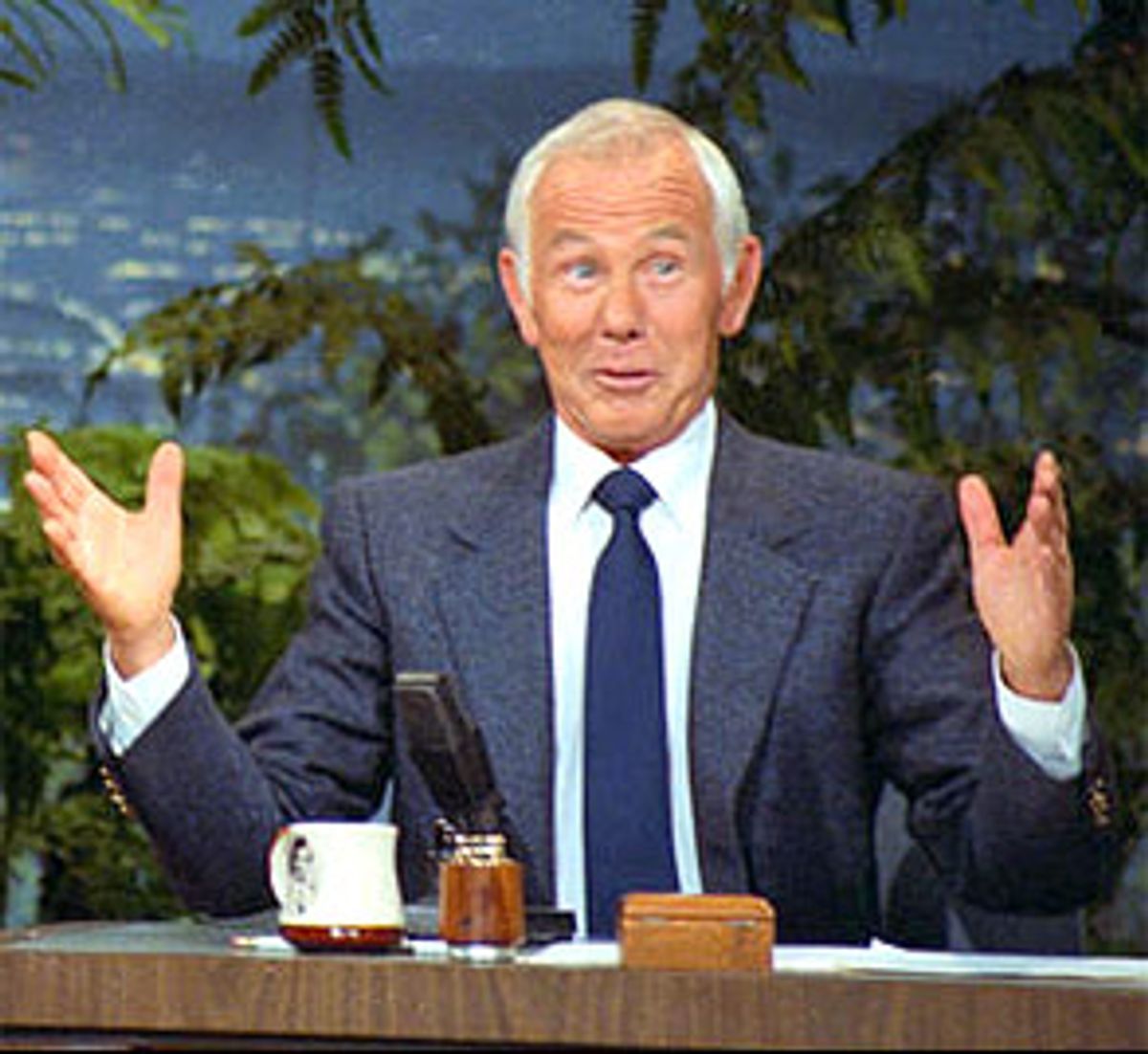

Journalists and television execs pricked up their ears. This was peculiar. Carson had waved goodbye to America in 1992 after hosting "The Tonight Show" for 30 years, and then abruptly vanished from the public eye. For eight years, no jokes, no interviews, no follow-up projects. Television's most recognizable figure, gone.

But here was Johnny, right there on the page, spoofing the pseudo-intellectual Miller's new gig as NFL announcer. According to the New York Times, Carson submitted the piece to the editors on the suggestion of humorist Steve Martin, and they printed it. And then, as if to dispel the sophomore slump, he published another two months later, a recently discovered collection of children's letters to Santa, as if written by Bill Buckley, Chuck Heston and Don Rickles.

Seeing him again was sort of like peeking through the curtains and seeing the divorced dad pull up in the driveway after an extended absence. Carson was a fixture to two generations of boob-tube Americans. Vietnam-era adults saw him as the nightly tonic to a pain-in-the-ass workday. Children sitting up past their bedtime marveled at a cocktailed Golden Age of celebrities, comedians and racy jokes. Each evening I used to hear the show's opening theme "Daaa dat dat da daa!" emanate from my parents' bedroom, accompanied by Ed McMahon's stentorian announcements, and it was like a signal. They were going to watch Johnny until they fell asleep, and I could do whatever I wanted. Until I could drive a car, I watched the show too.

Carson built up his on-screen family of regulars, and viewers learned to quickly identify the established comic premises. Johnny was the sideburned rascal, forever taken to the cleaners by ex-wives. Ed was the tippling Tonto sidekick who pitched for dog food. Doc Severinsen owned impossibly loud clothing and failed racehorses. Tommy Newsom: beige and boring. The shtick never varied; characters like Carnac the Magnificent and the oily Art Fern's Tea Time Theater continued year after year. This was old-school, steeped in vaudeville and radio, with the ribbon mike firmly planted atop the desk. Funny props, cute animals, a few caca jokes, ogle the cleavage, keep things moving. If it ain't broke, it stays in the show.

The most impressive feature was always Carson's opening monologue, sharp and topical, evolving with the nation's moods, delivered with a casual Midwestern air, textbook TV cool, each punchline set up with a completely plausible statement, as if Johnny were standing in line in front of you at the feed store, and turned to say, "Did you see this in the news?" When the material clicked, it killed. (Many maintain that Carson's constant hammering of President Nixon contributed to his eventual resignation.) And when a line bombed, Carson made an art form out of the recovery. ("You didn't boo me when I smothered a grenade at Guadalcanal.") In a narrow-casted, three-network world where comedy meant sitcoms and variety shows, his monologue provided an ideal cultural barometer for the nation, mixing in politics, scientific discoveries, fads and trends, strange news items, his divorces and even bawdy mentions about Dolly Parton or Linda Lovelace. If you craved a peek at the big bad adult world, there was really nowhere else to turn besides the first 10 minutes of "The Tonight Show."

Carson was born in Corning, Iowa, in 1925, and spent his formative years in Norfolk, Neb., performing magic and comedy under the name "The Great Carsoni." He served in the Navy during World War II, entertained college fraternity parties and worked as a radio announcer and disk jockey. While performing for audiences of farmers each day, he spent nights listening to tapes of radio heroes like Jack Benny and Bob Hope, studying their inflections and timing.

When television began to invade America's living rooms, Carson chased the new medium to Los Angeles, where he hosted a handful of low-budget comedy series, conducting phony interviews and performing skits and characters. The material was quirky and occasionally naughty, yet homespun enough to hit home with the heartland. Although he was popular, the shows weren't, and he ended up writing jokes for Red Skelton. His first big break came in 1957 as replacement host of the ABC daytime quiz show "Who Do You Trust?" When Carson inherited the show, he needed to hire an announcer. A big man from Philadelphia showed up for what would be a very bizarre job interview.

In his 1998 autobiography "For Laughing Out Loud," Ed McMahon recalls walking into Carson's office, to find Johnny standing at the window, looking out in silence. Finally he turned and asked McMahon where he went to school.

"Catholic University," McMahon answered. "In Washington, D.C. I studied speech and drama."

Carson replied that was very interesting, and thanked him for coming by. McMahon left confused, thinking perhaps he'd blown it, and didn't hear anything for three weeks, until the show's producer called and told him he will be wearing suits on the show to emphasize his size. He realized he got the job. He also saw a glimpse into the private shyness of a man who would be his employer and friend for the next 35 years.

As celebrities would later guest-host his show, Carson occasionally filled in for Jack Paar on "The Tonight Show," and when Paar left in 1962 Carson slipped into the slot, bringing McMahon along. A longtime jazz fan and sometime drummer, Carson retained Paar's house band, led by Skitch Henderson and featuring a young trumpet player named Doc Severinsen.

For the next three decades Carson crafted a 90-minute nightly cavalcade of sketches and guests that, although shot in New York and Burbank (after 1972), was most accessible to the unwashed masses between the coasts. His studio audiences were primarily tourists from the Midwest, and his writers injected this WASPish heartland flavor throughout every element of the show: a scorn for the pretentious, an appreciation for funny animals and strange eccentrics and a cosmic shrug about the inevitability of taxes, ex-wives and hangovers. The result was hundreds of moments that have become engrained in our psyche:

The segment in which Ed Ames threw a tomahawk at an outline of a human target, the hatchet stuck handle up in the crotch and Johnny ad-libbed, "I didn't even know you were Jewish." The Dragnet-style "Copper Clappers" wordplay bit, with a straight-faced Jack Webb. The scared marmoset that crawled onto Johnny's head and peed on him. The near-masochistic recycling of ukulele oddball Tiny Tim, staging his on-air wedding for 50 million viewers. The actor Jimmy Stewart tearing up while reading a poem about his dog. A man who rendered the national anthem by making flatulent noises with his hands. The winners of a bird-call competition. A loaded Dean Martin secretly tipping cigarette ashes into the cocktail of an oblivious George Gobel. An eccentric old lady who presented her beloved collection of potato chips shaped like faces of celebrities -- when Carson munched blithely on a chip, the woman nearly had a coronary, until he revealed a separate bag behind the desk.

Carson exploited politics, but only for quick one-liners, or to give room for his credible Ronald Reagan impression. The show was never about him, it was about the world he beheld. When he invited guests to come on the show, he listened with curiosity, took them seriously, and the audience followed his cue. Critic Kenneth Tynan profiled him for the New Yorker in 1978, and observed, "It is only fair to remember that he does not pretend to be a pundit, employed to express his own opinions. Rather, he is a professional explorer of other people's egos."

Carson had a soft spot for comedians, from insult king Don Rickles, to his idol Jack Benny, to ponytailed George Carlin, who gave America its first taste of network dope humor. Sweating young comics experienced their show-biz debut via Carson -- among them Jerry Seinfeld, Roseanne Barr, Jay Leno and David Letterman -- anxiously awaiting the "Good stuff!" comment of approval, or even better, the wave to come over and sit down.

Some moments never made the greatest hits clips. One night the material bombed so badly, Carson lit the pages on fire and solemnly tossed them into a wastebasket, accompanied by Severinsen playing "Taps." In 1974, a fat cigar-chomping man carrying a cocktail streaked nude across the set of the show, forcing NBC censors to black out the lower half of the screen; the streaker was arrested and later released, said Carson, for "lack of evidence." A newly successful Eddie Murphy was asked if he enjoyed buying things with his Hollywood money, and he answered mockingly with a blackface accent: "Hey Amos, get a loada that coat -- that's a mighty big watch there." An obviously unhip Carson watched helplessly as Murphy then invited his friend from backstage to come out and do an impression of Prince.

"Tonight Show" guests developed a reputation just for their appearances. A maniacal Mel Brooks ran amok for an entire program, bumping all scheduled guests. Comedian Buddy Hackett spent 15 minutes telling one anecdote about a corned beef sandwich. A seemingly irritable Charles Grodin purposely disagreed with everything Johnny said. Albert Brooks did celebrity impressions while eating various foods. Flamenco guitarist/sexpot Charo was perennially asked back to dance the "hootchie cootchie." A fully made-up Alice Cooper politely drank a can of Budweiser during his interviews. Don Rickles once congratulated McMahon with sincerity upon his recent marriage, then turned to Johnny and barked, "I give it about a week, tops."

Carson hit his professional peak during the indulgent late '60s and early '70s. "The Tonight Show" was then firing on all cylinders, square enough to make Hollywood's old guard feel comfortable, yet hip enough to appropriate the party. The show swung right from the opening theme, when Carson parted the curtain and blinded viewers with a nightly arsenal of Nehru jackets, noisy-patterned sportcoats, and neckties the size of beaver tails. This was America's late-night cocktail lounge, the televised nephews of the original Rat Pack. Guests smoked and drank on camera without guile. Marriage was just a punchline, as gleaming medallions nestled in thatches of chest hair, braless breasts spilled out of dresses. Guests never chuckled -- laughter was accompanied by a thrown-back head, a fit of cigarette coughing, a spill of the bourbon. Carson frequently erupted in a loud cackle, sending him out of his chair. The show often returned after a commercial break to catch Johnny drumming with pencils along with the band, after which he would turn to Ed and joke about their bender the previous night, like a couple of tomcats on the town chasing skirts.

It wasn't always funny business. I remember watching two "Tonight Show" incidents in particular, and thinking this is a window into how Carson really thinks and feels. The first, a bit with Carson chatting with McMahon about a new scientific study concluding that mosquitoes were particularly fond of extremely "warm-blooded, passionate people." Under the desk, Carson had concealed a prop can of insect spray the size of a fire extinguisher. As he mentioned the setup about passionate people, McMahon blurted, "Whoops, there's another one," and slapped his wrist, getting huge laughs and completely upstaging his boss. "Well then," answered Carson, "I guess I won't be needing this $500 prop, then, will I?" He pulled out the prop and tossed it aside, a nice recovery, but accompanied by a brief glare at McMahon.

The other, a moment in the middle of the show where Carson asked the audience if he could get serious. The studio quieted down, and he pulled out a copy of the National Enquirer, which had printed an article about his marriage headed for divorce. He addressed the camera directly: "I have not seen this until this morning. Now, before I get into this or say any more, I want to go on record right here in front of the American public because this is the only forum I have. They have this publication, I have this show. This is absolutely, completely, 100 percent falsehood ... I'm going to call the National Enquirer, and the people who wrote this, liars. Now that's slander. They can sue me for slander. You know where I am, gentlemen."

The move required balls of steel, and said to the world that "The Tonight Show" might be fun and games, but don't fuck with John William Carson. The Enquirer would print more stories about him, but they never sued.

It wasn't easy to be Johnny Carson. Nobody could tape 5,000 shows, interview 23,000 guests, without sacrificing some amount of personal life to the darkness. He ran through three wives and four producers, and developed a reputation as temperamental and emotionally distant. His three sons didn't see him that often, unless they worked on the show. A long struggle with the booze led to headlines for a drunken driving arrest. During one interview, he snapped at a journalist for not doing his homework and walked away from the table, leaving his then-publicist Gary Stevens to defuse the scene. At parties he either did card tricks, or didn't show up at all, preferring to stay home and tinker with hobbies like archery and astronomy. Other than endorsing a men's clothing line and producing the film "The Big Chill," most business investments were washouts: the DeLorean automobile, a savings and loan bank, TV sitcoms with Gabe Kaplan and Angie Dickinson, a bid to purchase the Aladdin Hotel in Vegas. His first and only concern was always the show. He'd worked in television since its inception and knew the golden rule: If the ratings dipped, you were history.

Running a talk show takes its toll on the host. Jack Paar would start crying and walk off the set. Dick Cavett has been hospitalized for depression. The newer successors like Letterman, Bill Maher, Conan O'Brien, Miller, Leno -- all of them reek of neuroses. But what sets Carson apart from them is that he exposed so much of himself for so many years. He went through his divorces and experienced colossal business failures, and yet somehow he was able to make it endearing to an audience. With the exception of Letterman on occasion, the next generation seems more internalized and tightly wrapped, less skillful at interviewing and more interested in interrupting with a funny line. What do we really know about any of them, except that Leno works hard and collects cars, Letterman has a mother and Maher jerks off before taping his show?

He threatened to retire for years, but kept renewing his contract, knowing that this was really all he had -- that the audience would never accept him as anything other than himself. Although he was successful as host of the Academy Awards, his lone film appearance was in a forgotten 1964 musical "Looking for Love," with Connie Francis. As the 1990s loomed, Carson found himself competing for ratings with more shows, more networks, more celebrities. Rather than end up like Jack Benny and Bob Hope -- tottering geriatrics, wobbling before the cameras to gasp a final breath of life-giving applause -- Carson saw the writing on the wall. He was in his late '60s, as was McMahon, and producer Freddie DeCordova was even older. America's sensibilities had in many ways surpassed theirs: less sexist, less Anglo-centric, less mannered. "The Tonight Show" was dated. Late-night comedy now belonged to Letterman and "Saturday Night Live." The old men had their fun, they made their money. It was time to step out of the way.

Carson's announcement that he was retiring gave NBC one year to scramble for a replacement, prompting a much-publicized power struggle between Leno and Letterman, whose show Carson had produced. Both men had guest-hosted several times. Whichever was Carson's personal choice, he wisely stayed out of the arguments. Leno got the job, and Letterman jumped ship to CBS.

On May 22, 1992, Carson walked onstage for the last time. No grand prime-time finale packed with celebrities. No guests at all. He just sat on a stool and talked, thanking the viewers and studio audience of friends and family, and ran some clips from over the years. It was a classy exit, and then Johnny Carson, by his own choice, went home with his wife Alex to Malibu and shut the door.

He popped up in a few TV cameos, appearing on Bob Hope's 90th birthday special in 1993, and the following year, during a Los Angeles taping of "The Late Show," was seen driving a convertible, handing Letterman the Top Ten list. But for the most part, he has remained silent -- a little tennis and poker, an African safari, a cruise on his boat to watch whales. Close friends were shocked to hear of his 1999 heart attack and quadruple-bypass operation. Nobody had realized he was even ill.

What has kept Carson busy is his John W. Carson Foundation, which over the years has donated millions to various charities, including medical causes in the United States and Africa, animal conservation leagues, a South Central Los Angeles youth group and an educational foundation set up by legendary fraud-buster James Randi. Carson's hometown of Norfolk, Neb., also boasts the Carson Regional Cancer Center and the high school's Johnny Carson Theatre.

Carson's most lasting legacy is the perfecting of television's late-night format. Leno, Letterman and O'Brien continue the traditional "Tonight Show" structure of an opening monologue, a live band and studio audience, the phony plants and city skyline, taped segments outside the studio. Bill Maher and Dennis Miller have both unabashedly copped Carson's delivery: standing in one place, hands behind their back, heels lifting off the floor. And Richard Simmons has inherited the Tiny Tim role of everyone's exploitable freak-guest. But with all the expanded cable channels and entertainment outlets, these programs are more a coveted opportunity to plug product, and less a forum for quirky potato chip collectors and has-beens with funny stories about sandwiches.

As he sits in Malibu, surfing through the channels, Johnny Carson must shake his head at television's evolution into the current jungle of hyperkinetic teenagers and staged "reality" shows and the endless parade of professional wrestling. He did what he could with the new medium, had a lot of fun, made a lot of money and met a lot of people, even if he'd rather not talk to them. And if he feels like contributing more to the world, there's always the New Yorker.

If I could rearrange history, I'd add to the last episode of Carson's "Tonight Show" his ingenious 1991 monologue "What Democracy Means to Me," delivered as a tribute to the Soviet republics created after the fall of communism. As Doc and the band played "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" in the background, Johnny summed up the totality of life in the land of the free:

Democracy is buying a big house you can't afford with money you don't have to impress people you wish were dead. And, unlike communism, democracy does not mean having just one ineffective political party; it means having two ineffective political parties. ... Democracy is welcoming people from other lands, and giving them something to hold onto -- usually a mop or a leaf blower. It means that with proper timing and scrupulous bookkeeping, anyone can die owing the government a huge amount of money. ... Democracy means free television, not good television, but free. ... And finally, democracy is the eagle on the back of a dollar bill, with 13 arrows in one claw, 13 leaves on a branch, 13 tail feathers, and 13 stars over its head -- this signifies that when the white man came to this country, it was bad luck for the Indians, bad luck for the trees, bad luck for the wildlife, and lights out for the American eagle. I thank you.

Shares