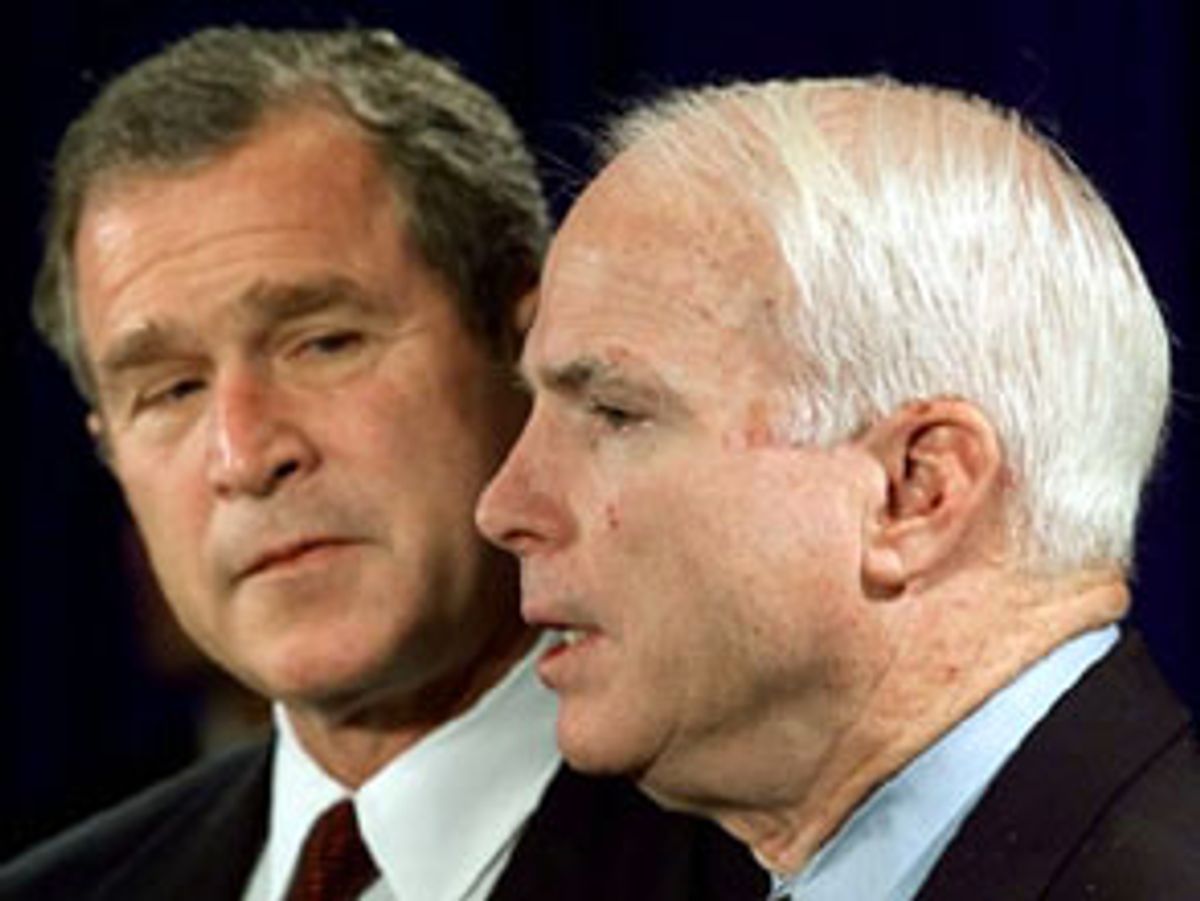

The most interesting political battle in Washington today isn't between Democrats and President George W. Bush, it's between Bush and his primary-season nemesis, Sen. John McCain.

Last week Bush's liaison to the Senate, Sen. Bill Frist, R-Tenn., attempted to begin negotiations with leading Senate Democrats on the patients bill of rights. But talks immediately fell through because Frist, apparently at the direction of the White House, refused to let McCain, the Republican cosponsor of the bill, in on the negotiations.

This is, of course, completely at odds with the image Bush is trying to sell to the voter. "I'm very hopeful that we can get a patients bill of rights on my desk, pretty soon," Bush said on Feb. 6, the day a bipartisan patients bill of rights was announced. "And the fact that John McCain and Senator Kennedy and others have come together is a good sign."

A "good sign" for whom? According to knowledgeable Democratic sources close to negotiations, last week Bush made the message clear to Democrats: If you want my support on the bill, McCain can't be a part of it.

This is remarkable not only because McCain is a member of Bush's own party -- not to mention, supposedly, a "friend" of the president's -- but because McCain is one of the two cosponsors of the Senate bill. And, according to everyone from the primary House GOP cosponsor, Rep. Greg Ganske, R-Iowa, to liberal Democratic Senate supporter Sen. Ted Kennedy, D-Mass., McCain's support is key to its success.

There seems to be one clear reason for Frist's attempt to elbow McCain out of negotiations on a bill that bears McCain's name: the personal animus Bush and his chief political advisor, Karl Rove, still feel for the man who came perilously close to toppling Bush in the primaries. McCain does not display the trait most treasured by the Bush team: Bush loyalty. The new president might also be sizing up the man who could, potentially, be his true nemesis in Congress: a Republican senator popular with Democrats, independents and moderate Republicans with the ability to build a majority impervious to a filibuster, and perhaps even to a presidential veto.

McCain has already made it clear that his agenda is not the same as the president's by working with Democrats on campaign finance reform, closing the gun show loophole and the patients bill of rights. This has fostered resentment in the White House among those who see the Arizona maverick as disloyal and an egoist.

For his part, McCain sees himself as doing what he thinks is right, fighting battles he was working on long before the ugly South Carolina primary fight that took place a year ago this week. No doubt he also sees himself making good on the bipartisanship Bush has promised but so far not delivered.

But whatever the reasons behind the animosity, it is now intruding on legislation that could affect millions of Americans. And, at least in this instance, the pettiness is Bush's.

This particular power struggle began Feb. 13 when Frist telephoned Sen. Ted Kennedy, D-Mass., on behalf of the Bush White House to begin a conversation on patients protection legislation, according to a knowledgeable Democratic source. Frist wanted to talk about reducing the cap on punitive damages for patients who sue their HMO in federal court, now set at $5 million in the bill already before the Senate.

Kennedy told Frist he would be interested in setting up a time to talk, but that Frist would have to talk to McCain as well.

"I can't do that right now," Frist said, according to a source close to Kennedy.

In an apparent attempt at an end run around both Kennedy and McCain, Frist then telephoned Sen. John Edwards, D-N.C., McCain's cosponsor of the Senate patients protection bill.

Edwards, too, told Frist that McCain would have to be in on the deal.

Edwards had phoned Bush Feb. 6 to talk about the bill and ways they could work together. That call has still not been returned, but last Thursday Frist again approached Edwards, this time on the Senate floor, to try once more to negotiate without McCain, but he was again rebuffed.

An Edwards spokesman diplomatically refrains from saying anything other than "Senator Edwards is looking forward to that conversation [with Bush]. He thinks their differences aren't that big and can be hammered out."

"I'm not going to comment on private conversations between my boss and other senators," said Frist spokeswoman Margaret Camp when asked on Tuesday about the Tennessee Republican's talks with Kennedy and Edwards. Camp then called back to dispute any report that Frist was trying to shut McCain out, noting that he called McCain on Friday afternoon. But that was a day after the Senate recessed and, of course, an excellent time of the week to leave a message with someone with whom you don't really want to speak.

Giving Edwards the cold shoulder while trying to freeze out McCain is only part of the administration's efforts, including an all-out attempt, led by Rove, to lobby members of the House and Senate to hold off on introducing the patients bill of rights. This effort ended with Rep. Charlie Norwood, R-Ga., the bill's House cosponsor last year, removing his name from the bill (and his spine from his skeleton) as a bipartisan delegation, led by McCain, went ahead and announced the legislation Feb. 6. Even then, according to sources, the White House didn't phone McCain to ask him if he and his colleagues could delay introduction of the bill.

Why the attempt to shut McCain out of the process? Since the GOP primaries last year, Rove has had a bilious vendetta against all those associated with McCain. No one should be surprised by that; vengeance didn't debut in Washington with Rove. But the ill-fated attempt to shut out the main Republican cosponsor of the bill is apparently the first time Rove's (and, presumably, Bush's) delectable combination of ego and manipulativeness has been an obstacle to a law being passed. (Rove, meanwhile, did not return calls for this article).

Egos often intrude in this business; Edwards and Kennedy have butted heads on minor issues surrounding the patients protection act. Both Democrats are being sized up skeptically by their caucus colleagues these days. Liberal Senate Democrats are scratching their heads at Kennedy's eagerness to be at the negotiating table with Bush, to be a player. Edwards, meanwhile, with his blow-dried, huckleberry manner and apparent interest in a 2004 presidential nomination, has rubbed others the wrong way.

Still, both have been able to hammer out their differences and get a bill into the hopper. Kennedy was approached last June by McCain during the last debate over a patients bill of rights. McCain, still fresh from a painful Republican primary loss to Bush, told the old-school liberal that he had heard so many complaints about HMOs and insurance companies on the campaign trail that "I'm with you from here on out." That meant something to Kennedy, who had never really worked with McCain on anything other than some government reform bills. And it meant something to Edwards that McCain's office was so willing to work on a bill with his.

Moreover, both Kennedy and Edwards know that shutting McCain out of the process, as Frist wanted, wasn't just bad manners, it was bad politics.

"McCain brings commitment and visibility," says a source close to Kennedy. Of course, he bucks up the courage of the cojones-lacking Democratic Caucus. But he also makes it tough for conservative Democrats like Sen. Zell Miller, D-Ga., to vote against the bill, and provides cover for other Republican senators who are eager to sign on but afraid of the repercussions from big businesses and HMOs that oppose the bill.

Bush's reaction, therefore, is instructive. He is willing to be bipartisan, willing to work with Democrats. Perhaps it's because they are not the real threat.

Shares