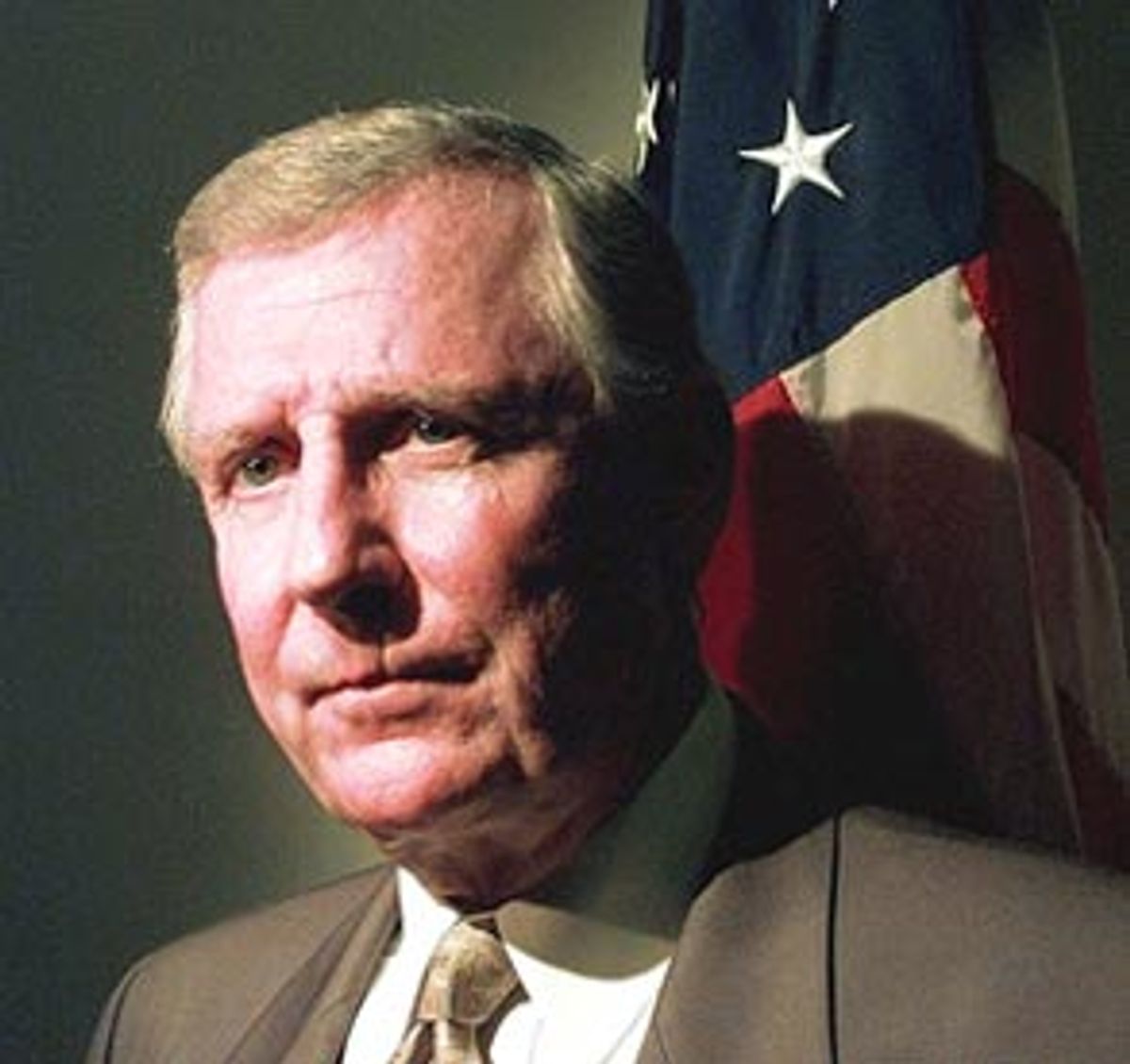

One of the most disturbing consequences of President Clinton's dubious 11th hour pardons may be the way they've served to rehabilitate the public image of Clinton's chief inquisitor, Rep. Dan Burton, R-Ind.

As chairman of the House Government and Reform Committee, Burton turned his panel into a one-stop shop for Clinton haters, mounting investigation after investigation at taxpayer expense. He may be best known for shooting at a "headlike thing" in his backyard in order to prove a crackpot theory that White House aide Vince Foster was murdered. In April 1998, Burton railed against Clinton to the Indianapolis Star: "If I could prove 10 percent of what I believe happened, he'd [Clinton] be gone. This guy's a scumbag. That's why I'm after him."

And he went after Clinton with a vengeance, hammering away at charges of campaign finance violations and other alleged ethical abuses. He once wrote a letter to ask the president whether taxpayer money was being used to underwrite the expense of mailings for a fan club for first feline Socks. He released transcripts of the prison conversations of former Associate Attorney General Webster Hubbell but edited them to remove comments that seemed to exonerate Hillary Rodham Clinton -- an act that earned him condemnation from Congress. He was later forced to apologize on the House floor.

Yet Burton had his own moral and ethical foibles that made him an unlikely judge and jury to condemn Clinton. In December 1998, Salon contributor Russ Baker revealed that Burton maintained sexual relationships with women on his campaign payroll, and used those funds to pay at least one longtime girlfriend who had no apparent job on the campaign staff. In a preemptive strike against Baker's story, Burton himself revealed that he had a 15-year-old son from another affair. The article also detailed allegations that Burton had used his congressional office to raise campaign funds, and had sexually harassed a Planned Parenthood lobbyist who came to talk to him about legislation.

The revelations in Salon's story, as well as other investigations conducted by the Washington Post and the Indianapolis Star, prompted Washington's Congressional Accountability Project to file a complaint letter with the House Committee on Standards of Official Conduct. Though the media had a field day with CAP Director Gary Ruskin's letter, the committee failed to act on Ruskin's charges.

The most explosive revelation in Salon's December 1998 report was the relationship Burton shared with Claudia Keller, who would later be described as a "ghost employee" on the Indiana congressman's staff by CAP's Ruskin. In government disclosure paperwork, the former model appeared in 1998 as Burton's campaign manager -- a position she ran from her home in Indianapolis. According to neighbors, Burton would frequently visit Keller's ranch-style home, where his supposed campaign manager would sometimes greet him at the door "wearing a teddy." Burton paid $2,400 to $4,000 each year in rent for that home between 1991-98. He also paid Keller a salary of $40,000 a year, plus expenses, to run his campaign. Additional payments were also made to Keller's business "Buttons and Bows" for her appearances as a clown at various campaign events.

Meanwhile, Keller was also on the payroll at Burton's district office. When asked by Salon what Keller did as a congressional staffer, Burton's spokesman had great difficulty explaining. According to CAP's own inquiry, Keller made $21,736 in her position during 1997, working an average of two days a week. In total, she had earned $157,664 since taking the position in 1990. In his request for an investigation, Ruskin asked the House Ethics Committee to "evaluate whether Claudia Keller performs official work commensurate with her salary, and whether she is or has been a ghost employee. If she is or has been a ghost employee, then Burton and Keller have engaged in a conspiracy to defraud the United States government."

Salon's exposi also presented evidence that Burton illegally used telephones in his congressional offices to raise money for his campaign. The allegations were similar to those lodged against then-Vice President Al Gore, who admitted to having made calls seeking "soft money" from his office phone. But Burton was raising money directly for his own re-election effort. Dan Moll, a fundraiser for Burton who was working on the House's civil-service subcommittee at the time, was overheard by a source trying to shake down money from a possible contributor from his subcommittee office. "You will give us money or we will never help you again," the source recalled hearing Moll say.

Other reports provided similar evidence, leading Ruskin to ask the Ethics Committee to "investigate the fundraising practices of Chairman Burton and Dan Moll to ascertain whether they have extorted campaign contributions from persons with official business pending before the Committee on Government Reform and Oversight, or Congress."

But the media reports and Ruskin's dogged efforts to pursue the charges fell on deaf ears in Congress. Under a law passed in 1997, it is impossible for civic groups or private citizens to file ethics complaints against congressmen. Under what the somewhat jaded Ruskin refers to as the "Corrupt Politicians Protection Act," all formal ethics complaints must be filed by a member of the House. The upside of the law is that it protects lawmakers from frivolous harassment. The downside is that no ethics charges have been filed, according to Ruskin, since its passage.

"Dan Burton is protected by the good old boys' network up on the Hill," Ruskin says, with an apparent weariness in his voice. "Members lock arms to protect one another. Many people think of the Democratic and Republican parties as some kind of mortal enemies that will expose absolutely every little wrong-doing in the other party and will do everything they can to out corruption. Quite the opposite is true. In most corruption cases, the Democrats protect Republicans and vice versa," he says.

Ruskin actually supports Burton's inquiry into the Marc Rich pardon. "I think that this investigation is 100 percent legitimate and a good idea. It's badly needed." But he's disappointed that the perpetual investigator has so long evaded investigation of his own ethical shortcomings.

Ruskin believes his ethics complaint was the victim of an era. Immediately following Clinton's impeachment, there was what the Wall Street Journal described as an unofficial "armistice" between House Speaker Dennis Hastert, R-Ill., and Democratic leader Richard Gephardt, D-Mo. In a March 8, 1999 article, reporter Greg Hitt wrote of a "shared desire to move the House away from the sometimes poisonous atmosphere of the Gingrich era." He then went on to quote Gephardt himself. "I hope we're beyond that," he said.

But one unfortunate consequence of that sentiment may be that Congressional leaders dropped the ball on a legitimate investigation of an elected official who had abused the powers of his office, Ruskin believes.

"This is just one of many examples in the House of Representatives where we simply aren't able to file an ethics complaint because neither party will hold the other party accountable for allegations of corruption," he says.

Shares