Kids fell apart after Columbine. Now, after Santana High School, they've got it together and have photos.

Or at least they took photos -- the police confiscated the film and, in at least one case, the video, in a gesture that unwittingly soothes us just a little: Please separate these children from their cameras. We don't understand their calmness.

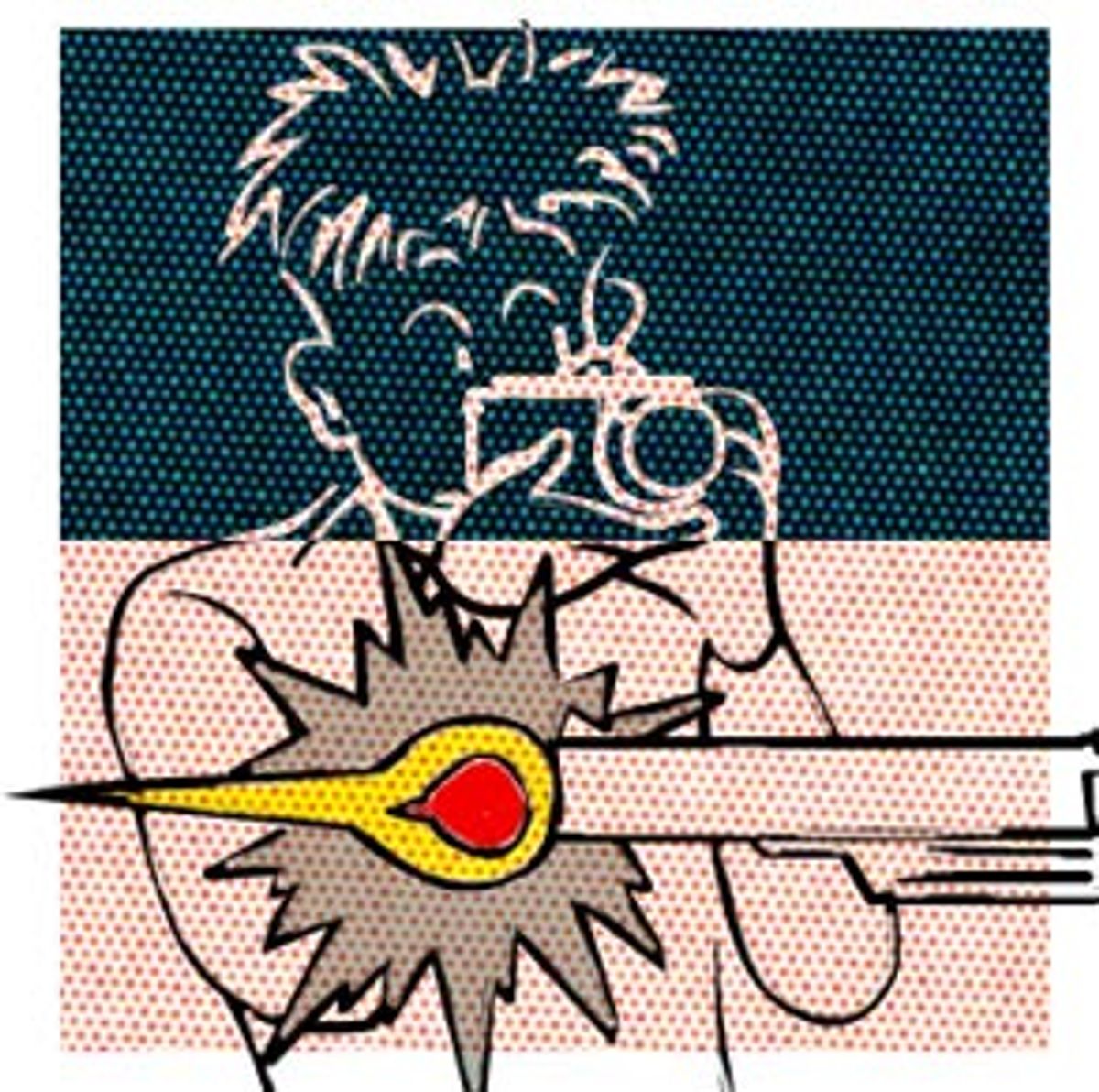

This is our hysteria. The shooting is hard to process -- there's lots to feel but little to say, at least until we start reminding ourselves of old metal-detector and gun-control discussions -- so we wring our hands over how we see these children respond. In a press conference, San Diego County District Attorney Paul Pfingst said what CNN showed us -- that parents were more upset than the kids in many cases. In the initial TV coverage, we heard students speak clearly and calmly about what had fired past them down the halls. Less than an hour after the shooting, they were eerily sophisticated. Their faces appeared unruffled and thoughtful, and they were media-ready. They weren't glib, but they were savvy. They speculated about cries for help; they referenced Columbine intelligently, without prompting from the interviewer.

One Santana student, John Schardt, got more airtime than any other. With gelled, spiky hair on top of a contemplative, serious face, he made the perfect teen media rep. He was assiduous, with complete sentences and a clear understanding of the meta-themes that invariably issue from school shooting stories.

"Everyone gets picked on, everyone takes it differently," Schardt said with astonishing poise. "People respond differently to beratement."

Schardt referred to the shooter's "sadistic demeanor," and later said that he'd taken both photos and video of the event. When Schardt's mother, Barbara, appeared in front of CNN's camera next -- equally pleasant, equally calm -- she, too, was well versed.

"It always happens somewhere else, but not in your own backyard," she sighed. "But it happened here."

Another boy -- these aren't girls, needless to say -- said he'd run back into the school to get his camera once he realized what was happening. When asked why, he mumbled that it was a big day, and he "wanted to remember it, or something." Even the TV anchor left that one alone.

Over the next couple of hours, the story evolved into something a little more recognizable. The CNN footage started to include shots of weeping and hugging on the school campus. One girl cried during an interview. And while it began to appear that the detached observer trend was perhaps only sparsely attended, Santana High's immediate aftermath never looked like Columbine's.

OK. People have their ways of responding to tragedy. An immediate reaction is a legitimate one, etc. As the post-violence healers will surely tell us, this was numbness or shock. We'll accept this but briefly worry about today's kids' access to instantaneous perspective. Minutes after death, they're pundits. We'll dust off our Oliver Stone-ish paranoia about our hypertrophied media society and the computer-fast processing of grief. Maybe someone will call the Santana photographers jaded, or even cynical.

"What's changed since the '50s?" someone asked Monday on a message board hosted by the San Diego Insider. "Why are kids so violent now? It can't be just because they are being picked on or bullied ... I honestly feel it's because home life has changed so much."

The poster was talking, of course, about the day's violence. But the words also articulate our more general concerns about kids these days. Why so unwell? Why are they getting worse?

The end has been near for a long time. Two and a half millennia ago, Plato was upset, too: "What is happening to our young people? They disrespect their elders, they disobey their parents. They ignore the law. They riot in the streets inflamed with wild notions. Their morals are decaying. What is to become of them?"

Our hysteria will become another issue to sort out in the wake of Monday's violence. In the minutes after a school tragedy like Santana, when the information is still mostly unavailable, it's hard not to grasp at the first things we see. CNN showed us calm teenagers, and this calm immediately affixed itself to our understanding of the catastrophe.

It must mean something that a relatively minor detail can stand out amid such larger sadness. It could just be another opportunity to grieve the loss of our children's innocence -- we worry this theme, unintelligently, every chance we get. But maybe we want shock on the Santana students' faces for more selfish reasons. Maybe that shock is what assures us that this still doesn't happen every day, and that we haven't fallen completely apart, not yet.

Shares