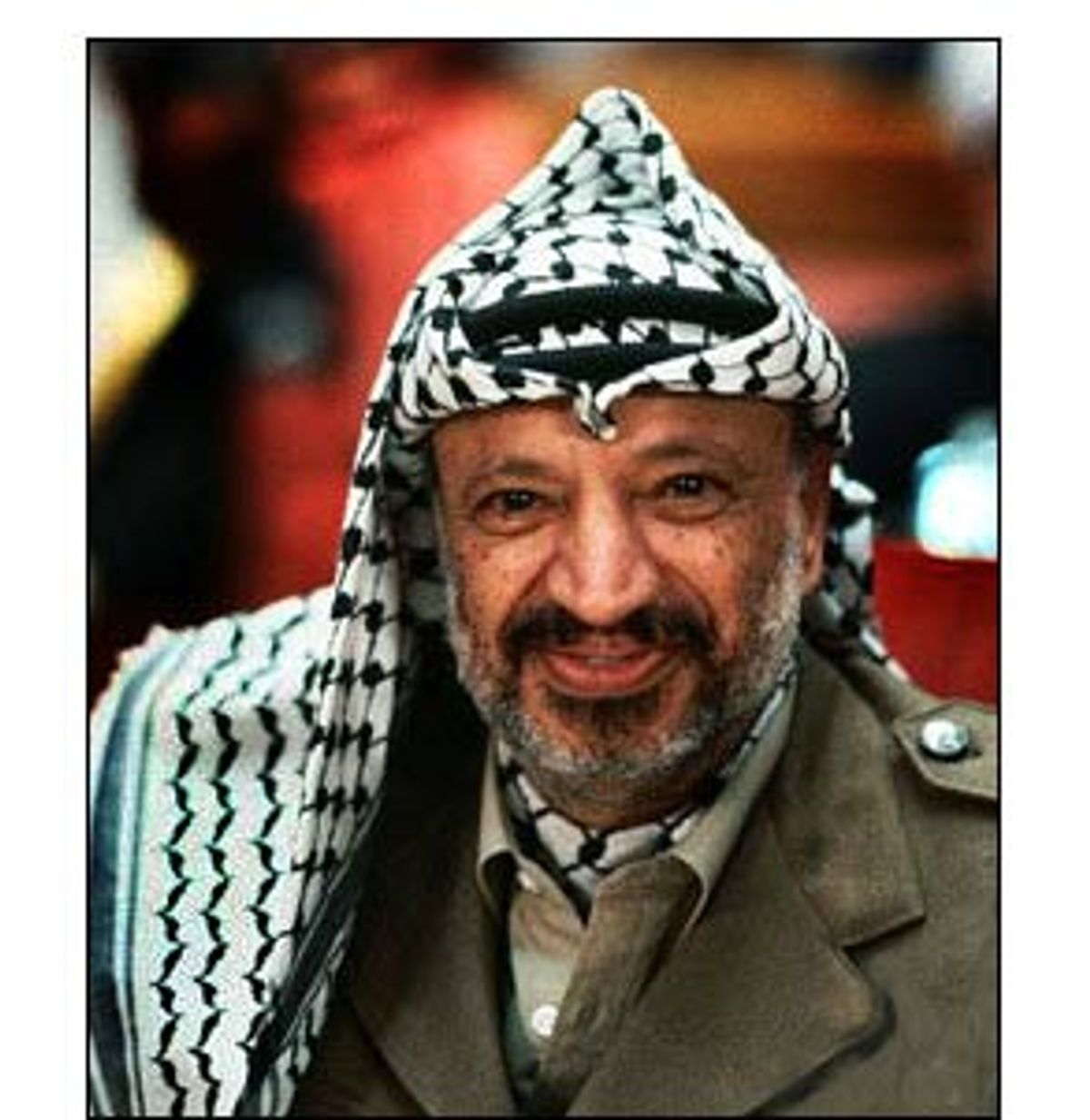

The first time I saw Yasser Arafat, I tracked his checkered head cloth as it moved down a double row of goose-stepping guards of honor to the stately oom-pah-pah tune played by a military band.

Arafat's trademark black-and-white keffiyeh moved slowly and steadily, no more than 5 feet 4 inches above a red carpet stretching from a lavish VIP lounge to a freshly landed aircraft. It framed Arafat's beaming, stubbly face as he personally greeted the first plane to touch down in Gaza. It was November 1998, the day of the inauguration of the Gaza International Airport, a perfect day for brass and pomp under the throbbing Middle Eastern sun.

The airport, the fruit of years of diplomacy, was a consecration of sorts for Arafat, the guerrilla commander turned jet-set dignitary, and a first step toward sovereignty for his embryonic Palestinian state. "Today the airport in Gaza, tomorrow the capital Jerusalem" promised a banner hung at the airport. Not far from the pageantry however, anarchy ruled.

A sea of ordinary Gazans in thongs and T-shirts, traditional embroidered dresses and jeans, had broken through the security lines separating the airport from Gaza's dusty streets and taken over the tarmac. Scraps from Arafat's dozen various security services celebrated in rowdy rings, carrying AK-47s over their heads as they chanted and danced. Women and children went for the sprinklers that had been laid down to breathe life into scraggly lawn patches and pierced the hoses to wash, drink and fill bottles with water -- a precious commodity in the overcrowded and underdeveloped Gaza Strip. Most people in the crowd had never seen a plane up close and could never afford to fly.

That opening scene is repeated every day in the 40 percent of the West Bank and two-thirds of Gaza that fall under Arafat's partial rule. There is not much authority in the Palestinian Authority. But there is plenty of misery and spontaneous combustion among Arafat's 3.1 million subjects.

Throughout the fall, when riots degenerated into deadly clashes, and up to the present, when Palestinians are waging a low-intensity guerrilla war against Israel, the division of powers in Palestine has remained more or less the same. Arafat, military garb notwithstanding, does the flying but leaves the fighting and nitty-gritty task of economic survival to the people. (It's against this backdrop that Ariel Sharon, the man whom many Palestinians blame for sparking the current wave of violence, assumes the mantle of Israeli prime minister this week.)

Among Western observers, Arafat's wiles and decisions are the subject of careful study and consternation. How could the Palestinian leader allow the territories under his control to spiral into violence and chaos? Why hasn't Arafat sought ways to put an end to an uprising that has already cost hundreds of lives? The widespread bafflement started after the collapse of the Camp David summit last summer, when Arafat walked away from generous Israeli peacemaking proposals without even making a counteroffer.

Thomas Friedman of the New York Times summed up the feeling of many in a column addressed to Arafat and written in the voice of then-President Bill Clinton last October: "You have an opportunity to deliver a Palestinian state, and to end the misery of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, and you're out there throwing stones and demanding an international investigation into the latest shootout. Are you nuts?"

"The Olso peace process was about a test," wrote Friedman again in February. "It was about testing whether Israel had a Palestinian partner for a secure and final peace. It was a test that Israel could afford, it was a test that the vast majority of Israelis wanted and it was a test Mr. Barak [Israel's former prime minister] courageously took to the limits of the Israeli political consensus -- and beyond. Mr. Arafat squandered that opportunity."

Publicly ridiculed by Clinton for the failure of diplomatic efforts at Camp David, Arafat is also widely blamed for the upsurge of terrorism in Israel. The dovish image produced by Arafat's historic handshake with Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin on the White House lawn in 1993 has been eclipsed again in people's minds by the image of Arafat as arch-terrorist. The Western media, however, could be giving too much credit to one man.

The demonization of Arafat is certainly at odds with the feeling on Palestinian streets, where Arafat's name and authority are increasingly irrelevant.

In five months of unprecedented violence, in which more than 400 have died, Arafat has addressed precious few words of solace or encouragement to his people. A victory sign here, a sound bite there -- but by and large the 71-year-old leader has distinguished himself by his absence from the battleground. Until Arafat met with U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell in the West Bank city of Ramallah two weeks ago, he had made only one other trip to the West Bank, where two-thirds of his subjects live, since the intifada broke out at the end of September. (He attended Christmas mass in Bethlehem -- hardly an electrifying moment in the life of embattled West Bankers.) At the same time, he has flown to dozens of capitals, relentlessly trying to rally support for Palestinian demands in a comatose Palestinian-Israeli peace process.

On the face of it, Arafat is in trouble. Arafat's international image, never very positive, has taken a serious blow over the past months. Domestically, his name is associated with the discredited Oslo peace process and, as the president of the Palestinian Authority, he heads a vast structure of ministries, civil services and security services now severely crippled by a 5-month-old Israeli-enforced siege.

Each time Arafat lands in Gaza, he is greeted with full military honors, but each time his plane takes off he seems to become more irrelevant to the lives of struggling Palestinians. "The leadership is not prepared [to fight] but the people are prepared," Marwan Barghouti, a 41-year old street activist who coordinates fighting on behalf of Arafat's Fatah party in the West Bank, recently contended in an interview with Between the Lines, a Palestinian magazine. Could Arafat, P.R. man for a desperate cause, be losing his mystique and grip?

By forbidding the movement of Palestinian workers and goods and refusing to transfer customs and taxes that Israel collects on the Palestinians' behalf, Israel has inflicted more than $1 billion in damage on the struggling Palestinian economy and virtually emptied the coffers of the Palestinian Authority. Funds for last month's salaries were patched together from European donations, and doubts hang over civil servants' next paychecks. United Nations Special Coordinator Terje Roed-Larsen warned recently that the fiscal crisis could lead to the collapse of key Palestinian institutions and Powell, during his visit to the region last month, urged Israel to ease its economic sanctions.

But Palestinian analysts dismiss as exceedingly alarmist scenarios in which thousands of Palestinian policemen, who have been ordered so far not to participate in the fighting, will go AWOL and use their guns as freelance fighters against Israel when Arafat's money dries up. Nor is there any great risk that Palestinian society will give up its allegiance to Arafat and sink into tribalism and anarchy. "Palestinians survived Israeli occupation. If resources dry up, Palestinians will change their way of life and manage on a subsistence economy like they did during the first intifada," says Ziad Abu Amr, an independent lawmaker in the Palestinian Authority's legislative council and a political scientist at Birzeit University. "If there are economic difficulties, Arafat becomes like the rest of the Palestinians," he says.

Although the Palestinian Authority is viewed as a spectacularly corrupt administration, Arafat is usually exempt from such criticism: His residence in Gaza is strikingly modest compared to the villas of some of his cronies, and he is known for his frugal lifestyle. If anything, Israel's economic sanctions against the Palestinians hold the promise that Palestinian fat cats will shed some of their privileges and reinforce Palestinian unity. Economic pressure will "perhaps clean Palestinian society of corruption," says Abu Amr. "It will also mobilize and radicalize Palestinians."

Ehud Barak, Israel's former prime minister and Arafat's counterpart in peace negotiations, may have been voted out of office in special elections last month for failing to protect Israeli lives and continuing to negotiate under fire. But the intifada, in which hundreds of Palestinians have died and many thousands have been injured, has not eroded Arafat's public standing. According to Ghassan Khatib, head of the Jerusalem Media and Communications Center, which regularly monitors Palestinian opinion, Arafat's level of support has remained where it was before the intifada last summer.

What the intifada has done, however, is reshuffle the Palestinian territories' informal class system. Five months of unending clashes have promoted the gunmen and teenagers who rule the streets with assault weapons, rocks and slingshots to hero status. The pictures of dead "martyrs" grace every shop and street corner and have become tragic role models for Palestinian boy fighters. The street fighters are usually disgruntled, downtrodden Palestinians whose living standards have deteriorated since the Oslo accords were signed in 1993 and third- or fourth-generation refugees who face no prospect of ever reclaiming the homes their forefathers fled in 1948. (The Oslo accords outlined a two-state solution to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, in which Palestinians would get a state on land occupied by Israel since 1967 but would presumably refrain from returning to Israel proper).

At the same time, the intifada has sunk the political fortunes of the economically privileged "Oslo VIPs"-- top Palestinian negotiators, security officials and aides to Arafat who prospered, while many Palestinians, stifled by checkpoints and borders, lost their freedom of movement and ability to make a living. But Arafat, who shared the 1994 Nobel Peace Prize with Rabin and Shimon Peres for making a historic choice against the armed struggle and in favor of negotiations, seems to be exempt from the fate of lesser Oslo dignitaries.

One reason may be that Arafat lacks any serious rivals. Barghouti, the charismatic Fatah militia leader in the West Bank, may command the attention of fighters in Ramallah, but he has no standing in Gaza and cannot match in Palestinian eyes Arafat's lifelong commitment to the Palestinian cause. A second reason -- and the key to understanding Arafat's paradoxical political longevity according to Palestinian analysts -- is that Arafat is both president of the Palestinian Authority and longstanding chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). "He can choose when to invoke the name and legitimacy of the Palestinian Authority and when to invoke the name and legitimacy of the PLO. He can transfer power from one pocket to another," says Palestinian lawmaker Abu Amr.

On the one hand, Palestinians believe the president of the Palestinian Authority erred in the peace process. Arafat's peace strategy did not work, says Khatib, the Jerusalem-based analyst. "He promised the peace process would bring an end to occupation and economic prosperity, but it failed," Khtib says. "Now Hamas [the militant Islamic Resistance movement which acts as Arafat's opposition] is saying: 'We told you so. Only by confrontation can we achieve our goals.' And that's what people are doing," he says. The Palestinian Authority is a product of Oslo (it was established to implement interim agreements with Israel), "so it's natural it should collapse with Oslo," adds Khatib.

On the other hand, Arafat is indirectly part of the current struggle against Israel and has retained the people's respect. As head of the PLO, an umbrella organization that includes his broad-based Fatah political party, he can capitalize on the participation of his party. "Fatah is in the lead of the intifada and hasn't gone against public sentiment," says Khatib. Fatah activists rally stone-throwers, put shooters in position and instruct people to fight on officially decreed "Days of Rage." Although Arafat probably does not hand out detailed orders to Fatah militia leaders, neither has he acted to stop them. He also continues to supply them with funds and weapons. "His position is not weakened by Hamas because Arafat's supporters and his party are the main force in the intifada," concurs Abu Amr.

Arafat began to feel the need for street credibility as early as last spring when Palestinians, frustrated by the slow pace of prisoner releases and land transfers promised by Israel, clashed with Israeli security forces on the day of the Naqba (literally "the catastrophe" in Arabic -- the day on which Palestinians commemorate the loss of their homeland in Israel's 1948 war of independence). The clashes, the most violent in several years, were a wake-up call to those who thought Palestinians would wait calmly for the peace process to yield tangible benefits after years of disappointments and missed deadlines.

Barak used the violence as a pretext to delay handing over control of villages east of Jerusalem to the Palestinian Authority and temporarily save his disintegrating coalition in the Knesset, Israel's parliament. The Israeli prime minister then pressured Arafat into accepting a summit at Camp David in July that would deal with the hottest issues on the table: the fate of borders, right of return for refugees and the division of Jerusalem and its holy sites. Analysts believe Arafat was reluctant to attend the summit and loath to accept Israeli proposals because he felt that "the street" was not ready. He allegedly told then-U.S. President Bill Clinton that he risked being killed if he returned with less than the full shopping list of Palestinian demands. By conceding nothing, Arafat was blamed internationally for the summit's failure but returned to Gaza to a hero's welcome.

"Arafat has accommodated himself with every Israeli prime minister since Oslo and accepted each prime minister's particular interpretations of the accord. He accepted the constraints Israel imposed on the Palestinians on the basis of accepting what you have and with the understanding that it was all transitional," says Mahdi Abdul Hadi, head of the Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs. "But when the time came to deal with the end of the game, he came back to the doctrine of Oslo: the establishment of a Palestinian state based on the 1967 lines." By offering less than 100 percent of the West Bank and Gaza, including East Jerusalem, Israel revealed its "deceptive intentions," says Abdul Hadi. Arafat, then, did the right thing by walking out on the talks. "He shouldered his responsibilities and gained more legitimacy and recognition in the eyes of the people and the Arab states," he says.

From the Israeli point of view, Arafat's rejection of Barak's offer, described in the Israeli press as the most far-reaching package of concessions ever put on the table by an Israeli prime minister, was an act of lunacy. It was read as the ultimate proof that Arafat does not really want to make peace with the Jewish state. Indeed, one of Arafat's failings, in his many years of leadership, has been his inability to convince the Israeli public that he is no longer a terrorist but a statesman and a peacemaker. Unlike Jordan's King Hussein, Arafat is not a charmer. King Hussein once flew to Israel to extend his personal condolences to the families of seven Israeli schoolgirls killed by a Jordanian soldier and managed to sway the country's hostile opinion by doing so. By contrast, after a Palestinian intentionally drove his bus into a crowded bus stop and mowed down eight Israelis last month, for example, Arafat condemned violence in general but dismissed the event as "a car accident." Arafat's refusal to proffer excuses or make conciliatory gestures was typical.

Many Israelis view Arafat as a sort of Middle Eastern Hitler, who has chosen shrewdly to extract Israeli concessions with the blessing of Europe and the United States but will only be satisfied with the ultimate destruction of Israel.

Palestinians, of course, disagree. "I don't see the Palestinian commitment to peace as a transient one," says lawmaker Abu Amr. "Arafat is saying: When it's time to struggle, I struggle. When Israel is ready for peace, I'm ready for peace." Nonetheless, most analysts say it is a mistake to ascribe to Arafat some great scheme or try to uncover a pattern in his decision-making. "Arafat is the maestro of tactics. He abides by no specific holy strategy, jumps from one thing to another and reacts to events," says Abdul Hadi. "He compromises between regional, international and domestic issues. This has given him the ability to survive."

Arafat's biography is studded with stories of close escapes and near-deaths. Arafat managed to survive repeated Israeli assassination attempts in Beirut, a plane crash in the Libyan desert that killed both his pilot and copilot and even a decade of political exile in Tunis. "From 1983 to 1993, he was in Tunisia far away from his people," says Danny Rubinstein, the Israeli author of a political biography of Arafat. "His people were scattered under regimes that were hostile to him like Syria, Jordan and Israel. But despite his isolation, Palestinians were loyal to him because he knows how to read the wishes of the people."

Arafat's caution during this intifada fits that pattern: "Arafat behaves according to the consensus of the people," says Rubinstein. "He's a survivor. He's riding the back of a tiger."

Although Arafat has tried in the past to move the Palestinian consensus from a position of total rejection of Israel toward coexistence with the Jewish state, he will not risk defying the public mood. "Right now, he has no reason to ask people to stop fighting," says pollster Khatib. "He could stop it if he had good reasons, if he proposed something in return." But after months of blood and hundreds of funerals, the public is more demanding and Arafat is "required not to sell out after all the sacrifices," he says. At the same time, the election of Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, a veteran right-winger who belongs to the same generation as Arafat, has reduced the likelihood that Israel will satisfy Palestinian demands and increased the prospect of all-out war.

As a result, no one should count on Arafat to lead his people out of the current chaos. As long as the street belongs not to frequent-flying diplomats but to desperate young men, Arafat will simply seek to sit astride the Palestinian tiger.

Shares